At the end of March, Chinese international student Rui Lin was saying goodbye to her friends every day in between taking her final exams. Most of them were Japanese exchange students who were preparing to return home. Their time studying at the University of Oregon got cut short due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At first, Lin’s friends were given a choice by their home universities to leave or stay in the U.S. However, the emails the exchange students received about the COVID-19 situation changed every day. In late March, the exchange students received a definite email telling them they were required to go back to Japan.

“Every day I’m sending my friends away,” Lin says. “I was kind of overwhelmed by that.”

While her friends were required to go home, Lin decided to stay in Eugene. Thinking that classes would return to regular in-person meetings after the first three weeks of spring term, as was first announced by UO on March 11, Lin decided to stay in the U.S. instead of returning to China.

She was one of many international students who chose to stay in the U.S. while UO classes went online. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has grown more complicated than it was when they first made their decisions. In the U.S., the number of cases rose by the thousands and healthcare providers started to run low on personal protective equipment. Recovering countries, like China, worry about a second wave of infections from returning nationals. Travel restrictions and quarantining upon returning proves to be a burden to those who go back home.

While COVID-19 changes daily life globally, international students face a unique set of challenges during the pandemic.

“We think that between two-thirds and three-quarters of international students are still in the U.S.,” Dennis Galvan, the dean and vice provost for the Division of Global Engagement at the University of Oregon, says about sample data taken by UO’s International Student and Scholar Services in March.

The students who remain in the U.S. during the pandemic must either stay enrolled in school or pursue an Optional Practical Training (OPT) in order to stay in the country on a valid visa. OPT allows international students to work in their area of study for up to one year in the U.S. on their student visas. If an international student chooses to not pursue graduate school or an OPT after graduating, they have a limited amount of time to leave the U.S. before their student visa expires.

Ugandan international student Noelyne Alitema says that the legal restrictions on international students living in the U.S. became more complicated with COVID-19. And with many countries closing their borders and airlines cancelling their international flights, some students may not even be able to return home at all, while scientists work to find a vaccine for the COVID-19 virus.

Alitema’s home country has placed heavy restrictions on people entering. Uganda requires incoming travelers to quarantine as soon as they arrive in the country. This can be done in a home, hotel or government facility where the person won’t be exposed to other people. While quarantining is an important safety measure, Alitema says that the hotels the government has approved are expensive, making it unrealistic for her to return home.

“From Eugene to Uganda, the cheapest ticket I could get would be $1,500. And then if I am to quarantine myself in a hotel that’s by the airport, a day could probably be like $500, and that’s for 14 days,” Alitema says. “It’s very unrealistic.”

And for international students who returned home, travel restrictions still complicate their plans for coming back to the U.S. As countries try to contain COVID-19, travel entry restrictions have been implemented worldwide to prevent further spread or a second wave of infection.

For example, the U.S. currently does not allow entry to people who have traveled to countries significantly affected by COVID-19, like China and Iran, within the last 14 days. A student from one of these restricted countries would have to stay in another country for 14 days before reentering the U.S., but other countries are implementing similar, if not harsher travel restrictions, making returning to the U.S. difficult for international students.

“Those would have to change in order for students to be able to come back,” Galvan says about global travel restrictions. “International students are in a tough spot, not knowing whether they can come back.”

While border closures and expenses of self-quarantine prove to be a major obstacle for some international students to return home, others believe that it is worth going through such measures because staying in the U.S. feels more dangerous.

Lin says that many international students fear the possibility of gun violence breaking out if supplies run low in grocery stores. She says that even her relatives, who all live in China, call her with worries about the dangers of staying in the U.S. In China, Lin would not have to worry about gun violence because of the country’s gun restriction laws.

“All my relatives are really worried because Americans carry guns,” Lin says. “This is what they’re afraid of most, not the virus.”

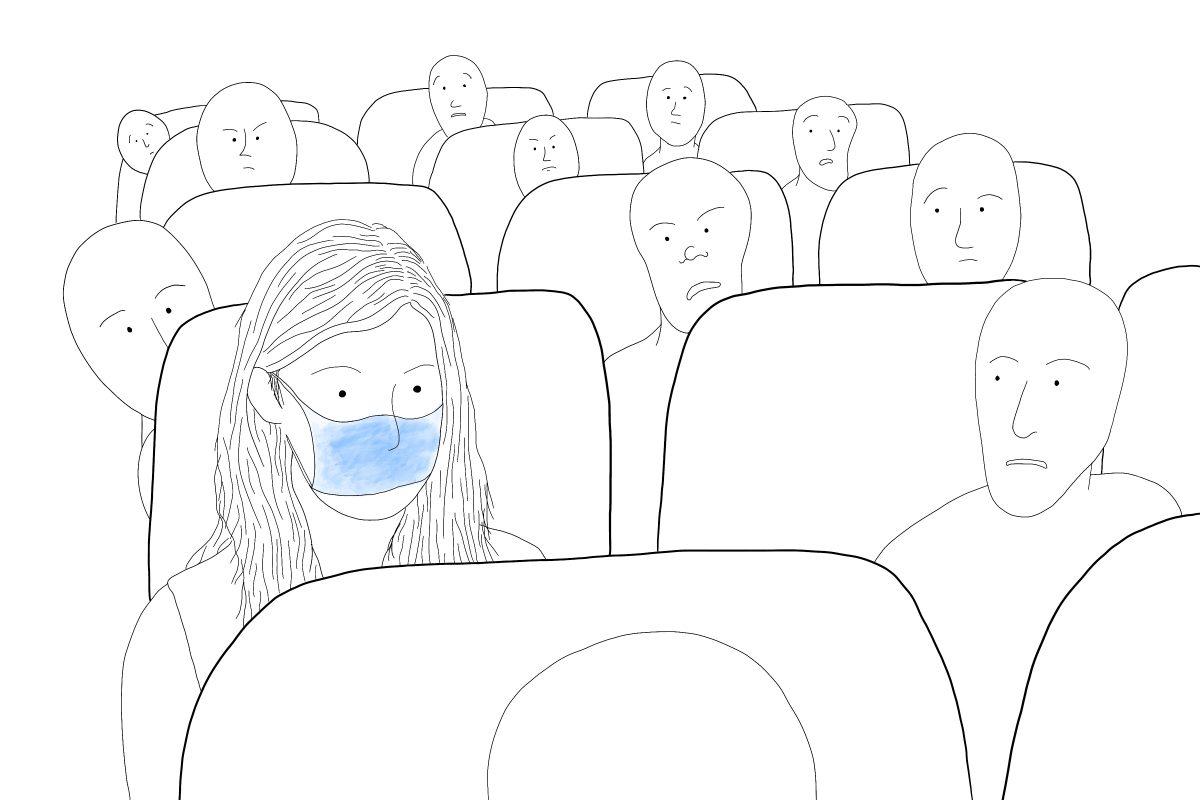

On top of worries of violence breaking out because of supply shortages, Asian international students worry about being racially targeted while staying in the U.S.

When news first broke about the spread of COVID-19, Asian international students were some of the first to start wearing face masks despite the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) initial measures saying that face masks were not effective in protecting against the virus.

Some of UO’s Chinese international students were buying masks in bulk and selling them to other students on WeChat. Other students received packages full of face masks from their parents.

Face masks are a part of normal life in East Asian countries. Someone might wear a face mask to prevent spreading diseases, protect against pollution or simply for stylistic purposes. However, face masks are not commonly worn in daily life in the U.S., which made them more noticable and alarming when people started wearing face masks to protect against COVID-19.

In February, Chinese international student Jane Shang wore a face mask on a flight from Seattle to Eugene to keep herself safe. She says she noticed that the passengers on her flight were watching her because of her mask. The people sitting near her tried to distance themselves from her. Shang says that she wasn’t bothered by the other passengers, because like her, they were worried about the new virus.

“I don’t really understand it,” Shang says about the negative reactions to people wearing face masks. “But I will do it to protect myself and other people.”

The racial targeting became even more explicit when Donald Trump called COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” on Twitter on March 16. Lin first learned about the tweet through screenshots posted on WeChat by other Chinese students. Trump’s remarks combined with the stories of racial targeting made international students feel uneasy about staying in the U.S.

“The international students, they were also afraid they would get discrimination when they wear masks,” Lin says. “I think they are more afraid of violence rather than the virus itself.”

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there have been increased reports of racial targeting of Asian Americans. The Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council has received nearly 1,500 self-reported hate crimes since they first set up their online incident report page in March.

International students at UO worked with the university to take action against the racial targeting through a multilingual inclusion campaign that took over the front page of the Oregonian on March 31. The ad campaign got almost 1.2 million views on the Oregonian’s website. The Asian, Desi, & Pacific Islander Strategies Interest Group at UO has also been working to make sure that the racial targeting campaign continues into the fall term.

“When people are hateful the solution to that is education,” Galvan says. “And when people are victims to that kind of hate, the solution is solidarity.”

As governments learn to control the spread of the virus, international students staying in the U.S. are able to watch their home governments from afar with a different perspective, says Lin.

On December 30, 2019, Dr. Wenliang Li warned his medical colleagues through WeChat of a possible SARS outbreak and the information quickly spread through Chinese social media. The Chinese police accused him of spreading false information and made him sign a letter of admonition. Dr. Li later died on February 7, 2020 from the COVID-19 virus, which he contracted while working at Wuhan Central Hospital.

Lin remembers feeling upset when she learned about how the Chinese government had initially responded to COVID-19 and Dr. Li’s warnings. It was the same feeling that Lin felt when she came to the U.S. and learned about historical events and political issues that were censored in China.

However, Lin’s initial feelings about the Chinese government’s initial response to COVID-19 has softened after seeing the effects of its strict quarantine measures. In China, police patrol out in public to reinforce social distancing regulations. In Lin’s hometown of Wenzhou, which sits on the central eastern coast of China, only one member of a household is able to leave every two days to get necessities. If people get too close to each other while going out, the patrolling street guards quickly break it up.

Lin says that stricter quarantine measures in China have allowed her parents to gradually return to normal life, while she remains in quarantine in the U.S.

“In China, when this coronavirus broke out, people were really willing to stay at home to work with the government,” Lin says.

Although many of Lin’s friends and family live in Asia, Lin says that she’s comforted by the fact that she can still keep in contact with them by calling. She says that she finds the time differences fun to navigate. When her mom is waking up in China, Lin calls her in the afternoon in Eugene to sing and play guitar for her.

“I think it’s a time to test friendship,” Lin says. “If your friends are away, and if you can keep in touch, it shows real friendship.”

Illustration by Garrett Dare

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)