The iridescent tote bag that Naomi brought to work every night before the pandemic contained a few essential items: several bottles of perfume, seven-inch white leather high heels, a spray can of mace and more outfit changes than the average woman holds in her closet.

Eventually, when Naomi decides to return to the strip club again, she’ll likely bring her baby pink mask to match her lingerie.

Naomi, a 22-year-old Lane Community College student who asked to use a pseudonym, has worked as an exotic dancer in Eugene and Springfield for the last three years. But when the sudden outbreak of COVID-19 sent the Oregon economy screeching to a halt in mid-March, she was sent into survival mode.

“When COVID first happened, I kept refreshing my phone over and over,” Naomi says. She was sitting on the couch with her roommates on the evening of March 23 when she received the notification that, due to an executive order issued by Governor Kate Brown, all non-essential businesses would close the next day. This meant no bars, no strip clubs and, for Naomi, no source of income.

“Even though I knew it was coming, I immediately burst into tears,” Naomi says.

On the night of March 23, her last shift at the club before the shutdown, Naomi was in the middle of leading an older man to the back room, one of his hands gripping hers and the other holding a Coors Light, when the overhead lights clicked on. It was over.

“I didn’t realize the club would be closing at midnight,” Naomi says. She returned to the dressing room and organized the evening’s cash tips into neat piles of 20s, 10s and singles, desperately trying to remain calm. She knew she needed a plan.

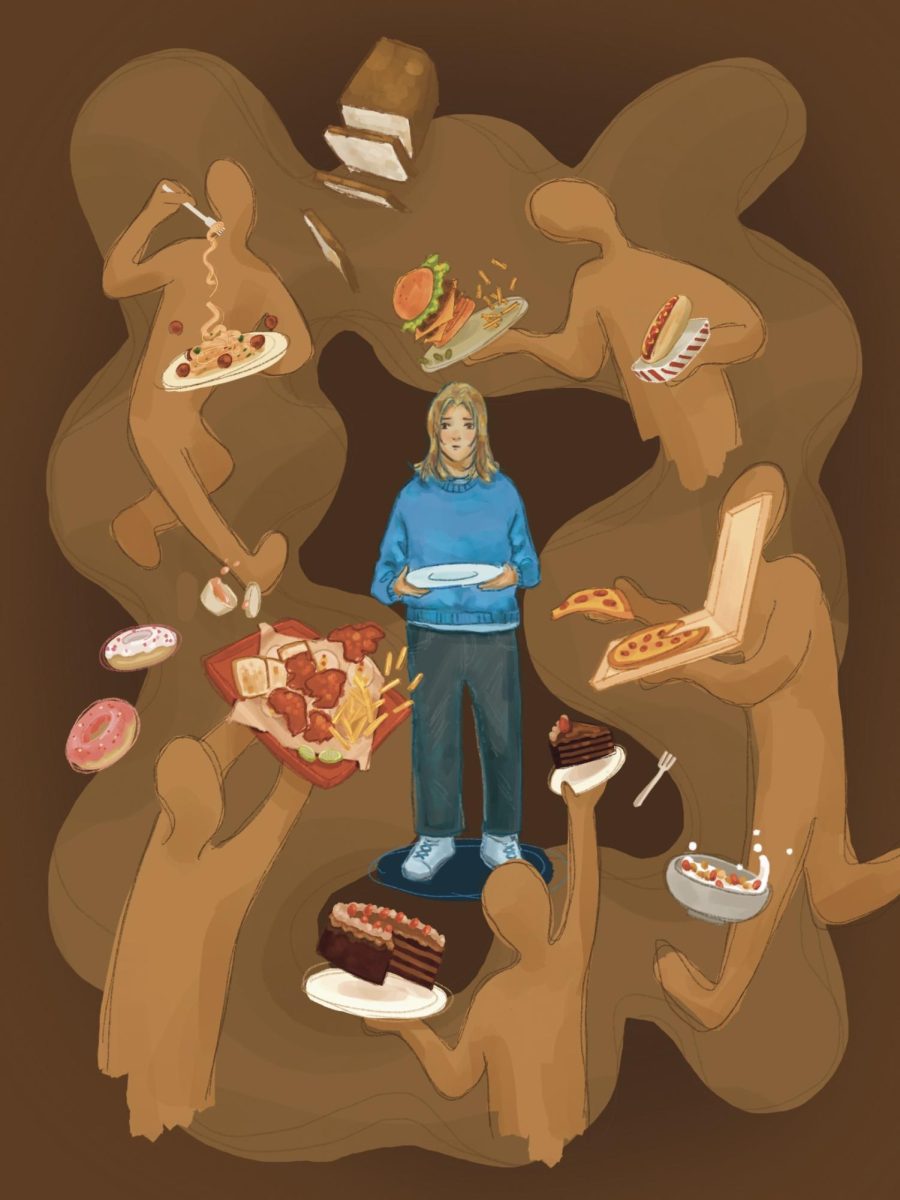

Naomi is one of the thousands of sex workers who were forced to act quickly when COVID-19 struck the U.S. In a business that requires physical intimacy, many exotic dancers needed to find a new and profitable outlet for their skills. Some women looked for work in a new industry, while others waited patiently to hear if, and when, their clubs would re-open. Others, like Naomi, turned to online sex work through sites like OnlyFans.

OnlyFans is a subscription-based website that hosts “models” and amateur content creators who sell photos and videos of themselves, which are mostly pornographic in nature. Although some pages are free, customers generally pay a fee from $4.99 to $49.99 to access a model’s main page. They can then tip extra money to receive personalized videos and messages. The result is a more personal experience than can be found in the seemingly endless sea of free online porn. Most models on OnlyFans are “real,” as in not professional porn stars, and will often respond and speak to customers on a more intimate level.

Naomi was not the only one to turn to online sex work in the wake of the pandemic.

The platform saw a 75 percent increase in users in March alone, citing 3.5 million new sign-ups, according to reporting by Complex. Although some of these users may have been new to the sex industry, Naomi believes her experience as a stripper is what has helped her grow her OnlyFans.

“What many people don’t realize is that a lot of men don’t come into the strip club purely for the sexual aspect,” she says. “A lot of them are lonely. They want to tell me about their divorce, their kids and just have a girl listen to them for an hour.”

When starting her OnlyFans account, Naomi tried to channel the same personality traits she uses at the strip club to make the interaction feel less “virtual” and awkward.

“I try to be as real as possible. Of course, there are naked photos, but I also show pictures of my plants, I talk about my meditations and crystals,” she says. “It’s like inviting someone into your life.”

Her bedroom in Eugene now looks like part new-age meditation retreat and part porn studio.

A small jungle of plants cascade down Naomi’s windowsill, interrupted by crystals jutting through the leaves and “charging their energy” in the sunlight. Her walls are covered in a large world map, dotted with pins on countries she’s visited and others she plans to travel to, and a Black Lives Matter poster from a protest she recently attended. A shimmering pole is fixed to the ceiling, though the room looks hardly big enough to host any acrobatic moves, and Naomi says she hits her head on the door of the closet more often than she would like. In the corner of the room is a lighting kit and a phone stand to help her record OnlyFans content.

While Naomi seems to have embraced her new career path since the pandemic, the transition to creating online content has been more difficult for some sex workers.

Christina Waterman, age 25, moved to Eugene in the beginning of March hoping to escape sex work. Having danced at strip clubs in Orange County for nearly five years, Waterman says she had seen her fair share of the dark side of the industry.

Some of her co-workers became dependent on drugs and alcohol – Xanax to calm nerves before a shift or cocaine to keep going – while others developed an aggressive personality from years of having to compete for their income. The initial benefits of a flexible work schedule and quick cash began to seem less and less glamorous.

Oregon was supposed to represent a clean start. She looked forward to the slower pace of life, the cold weather and being closer to her aunt and cousins. She started accounting classes and planned on applying for jobs at firms in the Eugene area. Waterman realized quickly, however, that her previous career came with consequences she hadn’t planned for. She had never claimed her cash tips on her taxes, so she found it difficult to prove her income. It was almost impossible to apply for a loan for a house or provide paperwork to make car payments.

Then COVID-19 hit. Suddenly jobless, Waterman learned about OnlyFans from a friend who had recently started an account.

After a few hours of research on Google, she decided to create a profile to sell nude photos and videos. It would be a temporary situation, she decided, just until the job market opened back up and she could find something more permanent.

But Waterman had concerns. While stripping comes with its own set of risks, the dangers of online sex work are unique. Photos and videos can be downloaded and saved indefinitely and strangers can sometimes discover personal information from thousands of miles away.

Even Naomi, who has no plans to quit the industry, has experienced negative consequences from online work. When she was 18, before starting as a dancer, she used to sell individual nude photos and videos to customers she found on Reddit. One time, when she forgot to answer a message request from an anonymous user, he sent another one. This time, it was a list: her full name, her parent’s names and occupations and the city she lived in. Naomi says she was terrified.

“I immediately deleted all of my accounts,” she says. “It was enough to scare me off doing anything on the internet for years.”

There is also the risk of family and friends discovering online profiles in the future. Waterman worries about explicit pictures making their way back to her daughter one day, who is now only four years old.

“I think I might talk to her about my past one day, maybe when she’s a teenager,” Waterman says. “I’d want to warn her what I’ve gone through before she thinks about it.”

Now, Waterman spends about an hour a day posting photos on OnlyFans. While Naomi seems to view her new business venture as exactly that, a business, by setting herself a schedule and coming up with new ideas for themed photoshoots and home videos, Waterman often recycles content that she already has on her phone.

“I think a lot of girls start an OnlyFans thinking it’s easy money,” Waterman says. “But it takes a lot of time to make that.” She says her new income from the website is barely a fourth of what she used to make at the club.

The idea that online work is easy money is a stereotype that many OnlyFans creators say they have to fight against. Naomi says she’s even read articles claiming that sites like OnlyFans take away the possibility of men finding love in “real life.” Many online sex workers, however, don’t see themselves fueling men’s loneliness or dragging them away from the real world, but offering them a reprieve from it.

“A guy sent me a selfie the other day on OnlyFans and I told him he looked cute,” Naomi says. The customer responded by saying it was the first photo he’d taken of himself in years because he was so self-conscious of his looks. He said he couldn’t remember the last time he’d gotten a compliment.

Naomi says many of the men she interacts with struggle with insecurities and are afraid to pursue women in real life, particularly during nationwide shutdowns that make socializing difficult. Paying someone from the safety of a screen can allow for a healthy outlet.

“Now he sends me a picture every few days, and I think he is starting to feel better about himself. That’s nice for me,” Naomi says.

For Waterman, the backlash against OnlyFans is amusing. Although she hopes to change paths soon, she believes the new era of online pornography is merely a different venue for the same thing humans have done for years. “[Sex work] isn’t going away,” she says.

It appears that despite rising numbers of COVID-19 cases across the country, strip clubs aren’t going away anytime soon either. On June 5, Lane County entered Phase 2 of Oregon’s COVID-19 response, which allows for the limited reopening of bars and restaurants, including strip clubs, as long as patrons remain seated and wear masks. Within a few days of the announcement, nearly all of the strip clubs in Springfield and Eugene scrambled to adjust their protocol and open their doors again.

“The club looks very different now,” says Brooke, a 21-year-old dancer and advertising student at the University of Oregon.

Brooke, who requested that her name be withheld from the article, first began stripping at Sweet Illusions more than a year ago. Now she works at a different club in Eugene. She was discouraged from revealing the location by her manager, who declined to comment for the article.

“When we re-opened we had to stay six feet away at all times, which can be really awkward,” Brooke says.

Brooke has an ethereal aura about her and laughs nervously as she talks, brushing her shoulder-length platinum-blonde hair from her eyes. When she demonstrates a dance on the pole in her living room, the straps on her flowery mask spin in time with her ruffled skirt, creating the dizzying illusion of a ballerina performing in air. It is clear that she has put effort into her craft.

“We have to work a lot harder to make money now,” Brooke says. Her typical nightly income has dropped, from more than $700 per shift before the pandemic to an average of $300 a night now. Because so much of stripping is reliant on physical contact, even if it’s just a flirty hand on the shoulder while making conversation with a customer, the new physical distance guidelines can be extremely hard to follow.

“A dancer [at Sweet Illusions] told me they actually pulled out a 6-foot yardstick the other day when a customer got too close,” she says and laughs.

Some local clubs haven’t followed safety guidelines after reopening. According to reporting by KEZI 9 News, local regulators with the Oregon Liquor Control Commission called for an investigation into Bohemian Tavern in Cottage Grove and Brick House Gentlemen’s Club in Springfield, after investigators found too many people crowded together. According to the OLCC, dancers, staff and patrons were all not wearing masks at Brick House Gentlemen’s club and dancers were too close to customers.

For Brooke, the risk of contracting COVID-19 is now simply another potential hazard of the job. “I’m already used to it,” she says.

For other sex workers, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the idea of stripping in-person unthinkable. Naomi says she will probably not return to dancing until a vaccine is found and plans on continuing to focus on her OnlyFans.

As of Sept. 2, she has more than 50,000 followers on her Twitter account dedicated to OnlyFans content and continues to grow her subscriber base day by day.

“Sex work is real work,” she says as she glances around her makeshift studio in Eugene.

In Naomi’s bedroom, the line that divides her from any other 21-year-old woman making a living is blurred. The photos of her friends lining her desk look like they could be found in any college student’s dorm room – even as they are juxtaposed with her intimidatingly-tall white leather boots piled on the floor, the markers of a job which many people still find taboo.

The world map on the wall, dotted with pins of all the countries she hopes to visit, is obscured by the large studio light and metallic pole that make her plans possible.

“With all this craziness that has happened, I am really proud of how I adapted,” she says.

For Naomi, creating content for OnlyFans is sometimes as simple as taking off her T-shirt and snapping some pictures. “Some of my followers actually like my lazy PJ pictures because they feel more authentic,” she says.