Story by Catherine Keck & Jacob O’Gara

Photos and Video by Maiko Ando

Down the steps and through the basement laundry room of an apartment building near campus, a once-abandoned storage room is now rented out by one of the tenants. The room is an organized chaos of boxes, small tanks, paint, tubs, lighting screens, dollies, and water heaters. Pumps and hoses snake across the cement floor. To the left of the entrance, a desk is centered in front of a four-paneled mural that reads, “Good Life.” Each panel features the silhouette of a different location: California, the Philippines, Maui, Japan – all of the tenant’s favorite locations.

This is the office of a curly-haired, wide-eyed twenty-four-year-old University of Oregon student who hardly appears to be the owner of a thriving business. His shorts, T-shirt, and weathered sneakers are even less indicative of his entrepreneurial success, or the fact that he is regularly flown across the world to do business.

This is the office of Ian McMenamin, a sustainable coral grower.

“Nobody thought I would make money doing coral,” he explains while examining a particularly exotic-looking breed of red mushroom coral.

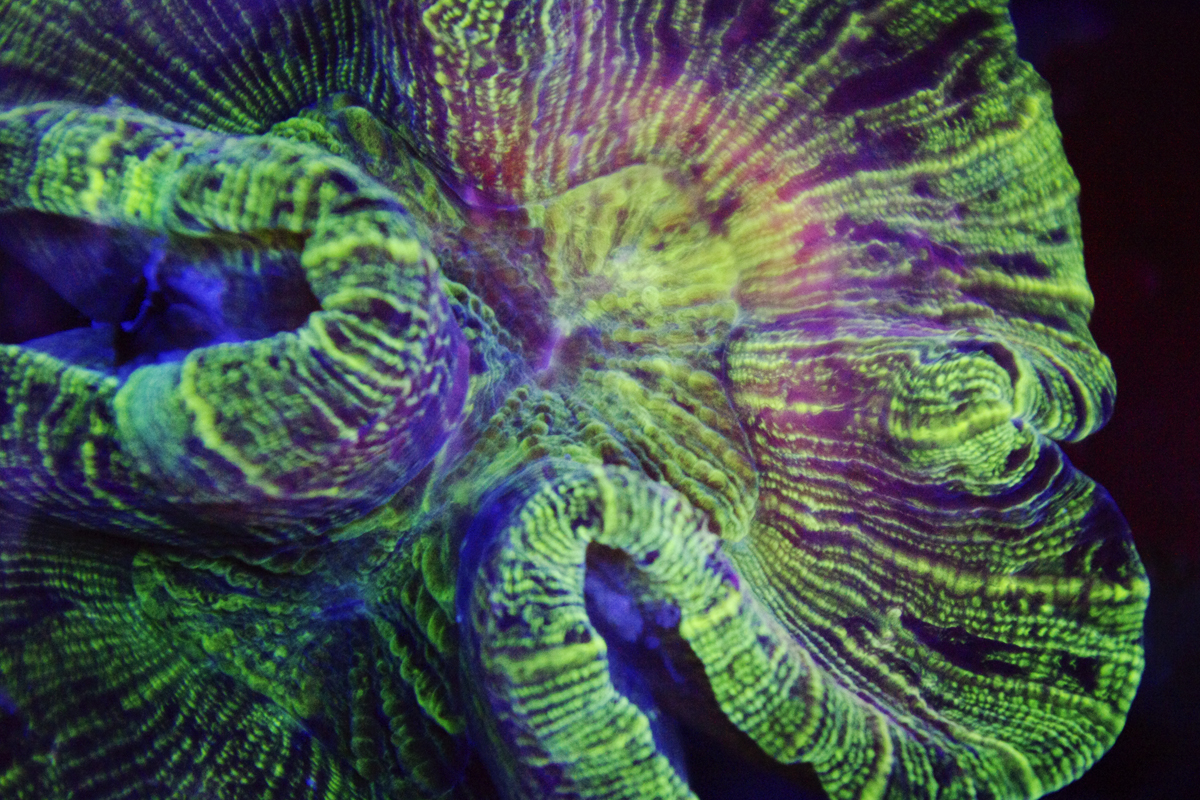

McMenamin uses his converted grow room to propagate sustainable coral – coral he harvests and reproduces artificially indoors – which he ships to locations within the U.S. He has created a name for himself as one of the most successful coral distributors on the West Coast, with first pick of coral that even major aquariums cannot obtain. McMenamin’s dedication to quality in a market flooded with “crappy coral,” as he calls it, has helped separate him from the competition, as well as his work in maintaining a sustainable business.

McMenamin has grown a lucrative company out of near nothing and now does business with some of the world’s wealthiest coral collectors. He has come a long way since he initially took interest in this obscure market.

At thirteen, McMenamin began working for under-the-table pay at a local fish store in his hometown of San Francisco. The business had a salt-water fish tank that held a small variety of coral, which he recalls was the big-ticket item for many of the store’s wealthiest clientele.

“I used to sweep by this nice little reef tank they had,” he says. “It was a salt-water coral fish tank, and I used to see the clients that would come in. These guys would have the Ferraris, the Bentleys, the suits, and the girls, and they’d come in and buy this beautiful coral. I was mesmerized.”

Coral, he thought, seemed like an attainable market with a narrow, but profitable demand. Intrigued, McMenamin decided to invest his small income into starting his own salt-water fish tank.

He began small. McMenamin recalls a number of mishaps during his earliest attempts at establishing a salt-water tank, such as pouring store-bought table salt into his tank, which he quickly realized is hardly the same as using actual salt water. Undeterred, he eventually managed to successfully establish a small salt-water tank. He added a number of exotic fish that he got permits to pull while traveling with his family in the Philippines, South Africa, the Caribbean, Indonesia, Australia, and Hawaii.

After deciding to begin adding coral to his modest tank, McMenamin quickly realized that propagating this species is no easy feat. In order to survive in a controlled environment, coral needs cleanliness and a constant steady flow of water. His first attempts were less than successful, and all his first coral failed to survive.

Rather than become dissuaded by his lack of initial success, McMenamin continued to invest every cent he earned into his new hobby. “I wasn’t going in and buying the $3,000 pieces, and letting it die. I was doing it with little thirty or forty dollar pieces,” he says. He continued to purchase inexpensive mushroom coral, which is one of three major types of coral species, and expanded on his collection as he could afford it.

Soon after, McMenamin began extensively researching coral growing extensively. Coral became his lifestyle, so much so that McMenamin recalls planning his dates with girls around trips to the coral store. Surrounding himself with other coral distributors, he heeded the advice of his counterparts and began successfully producing small, inexpensive pieces of coral to sell for profit.

By sixteen, he had invested nearly all of his coral profits back into his business and began purchasing larger, more exotic pieces of coral desired by his growing clientele. McMenamin saw the potential for large profit in this obscure market and continued to expand his small-scale business. By a strange turn of events, a teenaged McMenamin found himself distributing to the very men he’d once envied. He recalls meeting elite businessmen through Craigslist in shady parking lots, since at sixteen, he couldn’t really invite them over to his parents’ house.

“I would go out to parking lots in the middle of the nighttime – I mean, it looked like a straight drug deal – and these guys would come up with big cars, their suits half-done. We’d hold [the coral] up to the light, and it was always like, ‘Oh my God. I can’t believe you got this!’” he recalls. “We’d count out hundreds and I’d sit in my car and think, ‘This is ridiculous. I’m selling product to these people that I would never affiliate with.’”

Despite his obvious youth, the quality of McMenamin’s coral had his clients raving – and to other coral enthusiasts. By eighteen, McMenamin’s top buyers included CEOs and presidents of yacht clubs.

As McMenamin became more familiar with the sources from which his coral was being mined, he was faced with the harsh realization that coral is a dying species throughout most parts of the world. “The Philippines is just about the only place in the world that still has pristine corals. Everywhere else – the Great Barrier Reef, everywhere – coral reefs are dying,” he says. As a result of mining, pollution, and climate change, coral reefs are now endangered. Fishermen are rapidly depleting corals where they are still thriving, and human pollution is killing even protected reefs. As coral reefs are home to hundreds of species of oceanic wildlife, their extinction threatens the entire ecosystem.

Reassessing his methods of buying and distributing his product, McMenamin decided to focus on growing coral sustainably. “I really, really want to do something – that’s why I have taken the steps I have. I want to help, and I know I can,” he says. “And propagating this stuff indoors, that’s sustainable.”

Since moving to Oregon two years ago, his business has expanded to include multiple headquarters nationwide. “I feel that in the next twenty years we’re not going to have reefs . . . that’s why I’m pushing so hard right now. Most of the people here will never see a piece coral in their life. Ever. I think it would be great to let people see the beauty of coral.”

Today, 75 percent of his coral is sustainable, meaning that each individual piece of coral that he obtains is the last of that species that he’ll have to pull from the ocean.

Now, McMenamin is focusing on expanding his coral growing to be wholly sustainable, and hopes to aid in slowing the rapid depletion of endangered coral reefs.

“So once these countries start putting the money into cleaning their waters up, we can ship it right back to them,” he says.

The Quarrel over Coral

According to marine biologists, the international coral black market could kill us all.

If clumped together, all of the coral reefs on Earth’s ocean surface would occupy a space about the size of West Virginia. Despite this small surface area, a quarter of all marine wildlife considers the world’s coral reefs home. However, studies suggest that one third of all coral reefs are at high risk for extinction. Rising temperatures in the oceans, pollutants caused by human activity, and coral “headhunters” who illegally sell the endangered species for profit, contribute to this destruction.

Coral reefs host many species of fish and other marine creatures, and their devastation would kill most of these inhabitants. The loss of a quarter of all marine life would cause the oceanic food web to collapse, affecting billions of people around the world who depend on the ocean’s ecosystem for nourishment and economic prosperity. Studies estimate that coral reefs provide $375 billion in goods and ecosystem services, while providing food and livelihoods for 500 million people.

Fortunately, work is being done to prevent this apocalyptic scenario. In cooperation with international organizations, national governments have set up Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), zones designed to restrict human activity and development. Another method of coral protection, especially from collectors, is stiffer penalties for the transporting, selling, and buying of illegally obtained coral. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) regulates the smuggling and trade of wildlife, including species of coral on the verge of extinction. Despite the fact that many types of endangered coral are protected by international law, some coral bandits continue to break the law.

In 2007, Gunther Wenzek, a German national who owned a company called Cora Pet, was arrested in Portland, Oregon, for trying to smuggle forty tons of endangered coral hidden in shipping containers into the United States. Wenzek had been on the Justice Department’s radar since earlier that year, after a customs agent in Portland seized a shipment of endangered coral that Wenzel was smuggling in from the Philippines. Wenzek now faces three years of probation and a fine of $35,000.

Then, in June 2010, a couple in the US Virgin Islands was arrested for smuggling black coral – a species protected by CITES – to the islands. Ivan and Gloria Chu were sentenced to a combined fifty months in prison. Each was also sentenced to pay a fine of $12,500 – pocket change compared to the almost $200,000 they raked in from their contraband coral operation between 2007 and 2009.

Ultimately, the quarrel over coral between those who wish to preserve the ocean’s natural, living palaces, and those who wish to exploit them will come to a straightforward end. Either the existing coral reefs will remain, or they will be exhausted by a combination of disintegrating pollutants and collectors armed with hammers and dynamite.