Story and Photos by Leah Olson

On a balmy April afternoon, artist Ken O’Connell sits in his office, chatting about art supplies, tiny Italian villages, and Japanese Anime conventions. Quickly, one thing becomes clear: Ken O’Connell would be the perfect travel companion. He isn’t content with simply snapping a photograph of a beautiful doorway or cathedral on his travels. Instead, he chooses to document what he sees in sketchbooks, seventy of them to be exact.

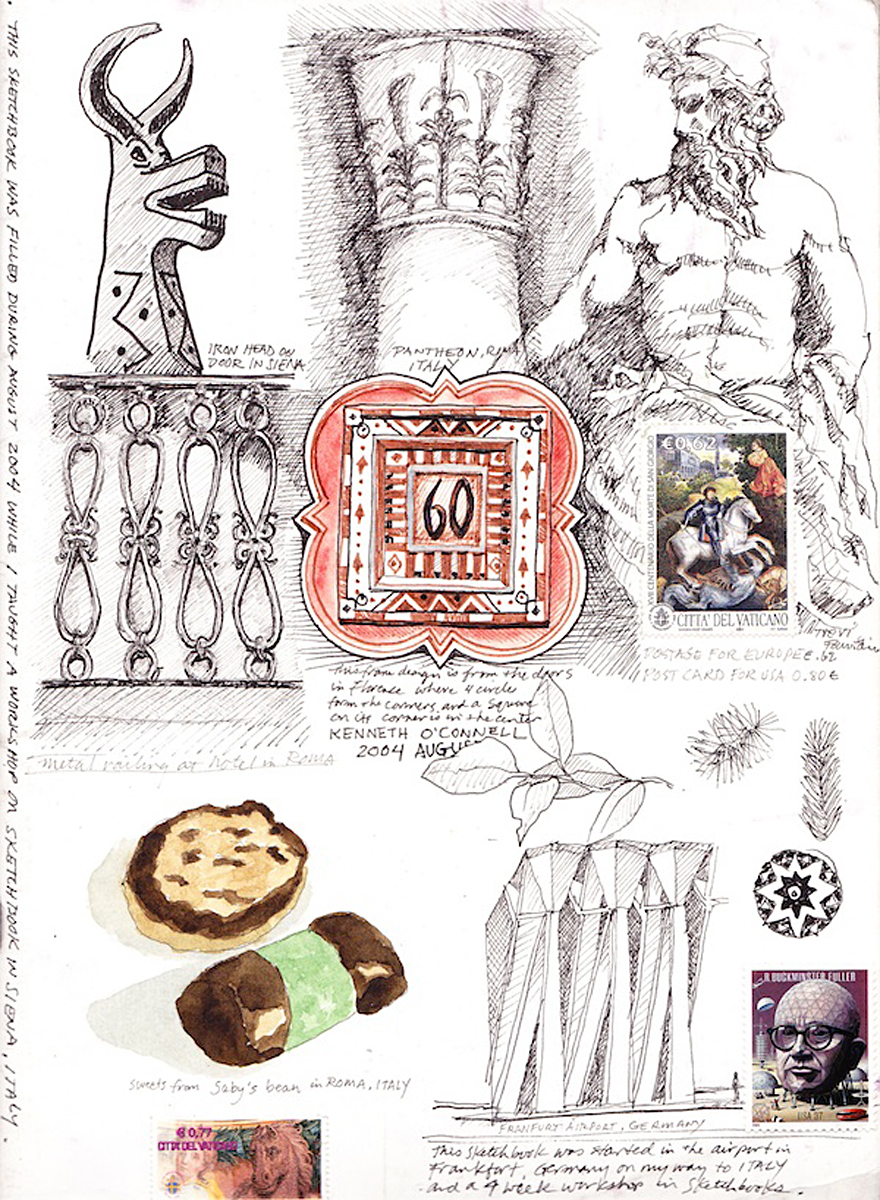

O’Connell’s collection of sketchbooks are individually numbered with the locations he visited while filling their pages. A peek inside the cover of number sixty-eight reads: “Canada, Japan, Germany, Oregon.” The pages burst with pencil drawings, vibrant watercolor scenes, haphazard notes to himself, various addresses, and stamps from around the world.

O’Connell’s life, like his sketchbooks, is packed with color and creativity. As a professor emeritus at the University of Oregon’s Art Department, he teaches digital arts classes and will begin a product design class in Portland summer 2010. He also is the president of his own company, Imagination International, Inc., which imports brightly colored Copic markers from Japan.

The First Sketchbooks

O’Connell, a self-proclaimed “city kid,” was raised in Oakland, California. He grew up observing his grandmother, Etna Kyle, piecing together scrapbooks and collecting stamps and coins sent via friends and relatives from around the world. O’Connell’s fascination with documentation and information gathering can be traced back to her, he says.

The first volume in O’Connell’s sketchbook collection is dated 1960, when he was a junior in high school. Prompted by a teacher, he began using his sketchbook to gather information about places, things and people.

“If I wanted to learn how to draw something, I would use the book,” O’Connell says. “If I wanted to learn how to draw a goat, I would go out to the country fair and find one to sketch.”

Compared with the vibrant pages of his latest sketchbooks, O’Connell says that for the first few decades of sketching he used very little color. O’Connell filled pages and pages of white paper with drawings and information, which he says have become an organizing factor in his life. Besides acting as a visual documentation, O’Connell also credits them as helping to drastically improve his writing and drawing skills.

The Evolution

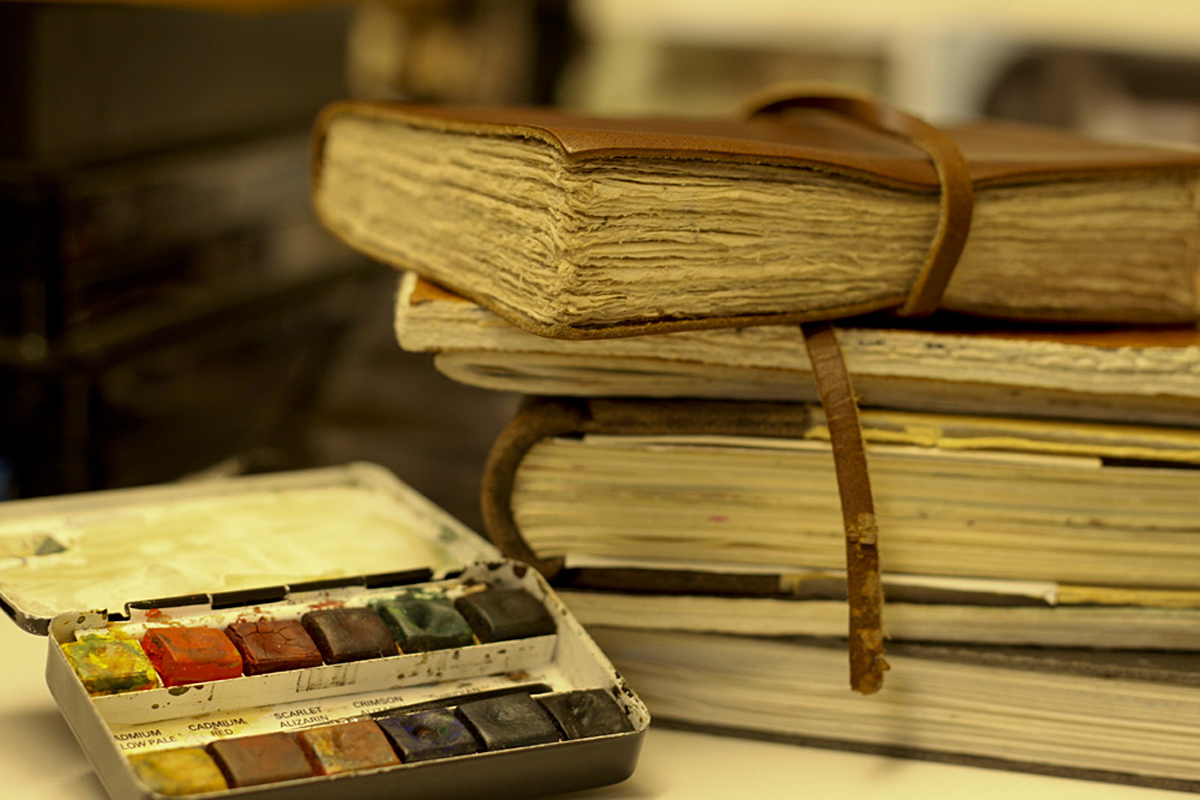

O’Connell’s sketchbooks have evolved from the inaugural volume back in 1960. A stack of them sit on a desk at his University of Oregon office. One has a black embossed cover and a spiral metal binding. Another has a yellow, marbled cover with tattered corners and a brown spine. A third is small but wide. It was a gift from one of his daughters after she returned from a trip to Nepal. Another of the sketchbooks contains heavy, rough paper and is covered with floppy brown leather. A length of leather string wrapped around the pages holds the book shut. Unwrapping the string and flipping through the pages of notes and drawings feels like stepping into a chapter of O’Connell’s life.

On a two-page spread is a scene from Stroncone, Italy: a brick tower with arched window openings in the foreground, an angular crane jutting into the sky in the background. Drawn by O’Connell in sepia toned pen and muted watercolors, it is the juxtaposition of old and new. From his pen marks and brush strokes, it’s as if the viewer was there, sitting next to O’Connell as he observes and draws, maybe for an hour or maybe for a day.

O’Connell says sketching is how he gets to truly know and understand a place.

“It’s all about taking the ordinary and making it spectacular,” O’Connell says as he flips through one of his books. “You’ve got to find the magnificent in the little things, like a pastry, or a window, or a tree.”

When O’Connell is teaching others about drawing, he emphasizes the transformative process and connection between seeing a place and sketching it.

“It transforms you from not knowing it, to knowing it,” he says. “Moving from no understanding to understanding takes time and takes questions.”

O’Connell says it’s imperative to set aside time for sketching. Taking time to look at something, understand its form and purpose and then transfer that understanding to a drawing creates an intimate knowledge and personal connection to a place that cannot be obtained from sitting on a tour bus.

For example, one day when O’Connell was in Stroncone, Italy, he went out to satiate his appetite with a pastry. Before eating his purchase, he sketched the flaky layers and golden brown finish. The pastry baker and coffee bar owner saw the drawing and was so pleased with it, she asked to sign the drawing. She also marked the upper right corner of the page with the shop’s signature stamp. In an enclosed black square above his drawing, the stamp reads: “au CAFFE CASTELLO Piazza della Liberta.”

“The sketchbook becomes like a portable studio and an exhibit,” O’Connell says about the baker’s pastry validation. “And then, it becomes a connection. It becomes significant to you because you get to know it.”

Sketching With Students

O’Connell has turned his passion for sketching into a means for world travel. In addition to classes in Oregon and Washington, he also leads sketchbook workshops in Italy.

The Italy trips began in 2003 when O’Connell took a group of University of Oregon art students to Siena. When he returned from the trip, he showed others his drawings, which sparked the interest of adult students. Soon after, O’Connell began organizing sketch trips to Italy with older students interested in drawing and learning how to capture the art of travel on paper. This summer will mark his fifth Italy sketch expedition.

O’Connell has toured and sketched in Italy’s major towns like Rome, Florence and Venice, but he prefers to take his students to smaller locales. On the first two trips, O’Connell brought his students to Siena, and on the last three they toured Umbria.

“The students love these little towns,” O’Connell says. “They don’t feel as much pressure in a small town with no tourists.”

O’Connell’s traveling sketchbook workshops are intended to create a solid community for all the participants. The students interact with the community they’re sketching and, O’Connell says, often learn a lot more than just how to draw.

“We’ll join in a community for a couple of hours. We study it and pay attention to it,” he says. “That’s also the key to personal relationships, it’s about paying attention.”

The Sketcher’s Advice

O’Connell says one of the biggest hurdles to get over when learning to sketch is to take the sketchbook off the pedestal. He encourages students to use the sketchbook as a vessel for learning about color, spatial relationships and shapes, but to remember that there really is no such thing as “messing up.”

“Art, at its fundamental basic, is about experimentation,” O’Connell says. “You should challenge yourself by experimenting with things.”

When O’Connell unzips his own shoulder bag, he pulls out thick Copic markers, three compact watercolor sets, and a gallon sized Ziploc bag filled with pencils. Even though O’Connell totes around pounds of art supplies, he says when students go out on location to sketch, he encourages them to be sparse about their choice of tools. The fewer tools a student takes, the more the experience becomes about drawing and less about the brushes, colors, pencils and pens.

“I try to get people to avoid being too precious about their tools,” O’Connell says. “They’ll look at them and think: ‘These look more important than I am!’”

O’Connell gives his students tips to develop their sketching skills and gain confidence in their talents. A full, empty white page can be daunting, O’Connell says. So, instead of attempting to fill a full page, O’Connell advises students to break up the space with boxes and dividers. This encourages smaller sketches that are more do-able than full page drawings.

O’Connell says students should have a basic and portable sketch kit before they start adding fancy tools and mediums. The basic kit should consist of two sketchbooks, one large and one small, some colored pencils and a brown ink, or sepia toned, pen for line drawings.

Once students start their own book, he says it’s helpful to put dates and times on pages.

“You can start using it like a clock,” O’Connell says. “A sketchbook has a powerful memory trigger. You go back and you can remember the stories behind the drawing.”

Traveling Forward

Sitting on a swivel chair in his office, O’Connell leans back and puts his hands behind his head. Two of his office walls are smothered with art posters, cards, sketches, photographs and carved wooden masks. On the other two walls, from floor to ceiling are long bookshelves, about to explode with papers, art supplies, VHS tapes, CDs and books in several languages.

“The brain loves to learn things,” O’Connell says, with one of his sketchbooks open on his lap. “Sketching keeps the mind alert.”

O’Connell says he’ll continue to fill blank sketchbook pages. Of course, he doesn’t mind that his passion for sketching helps him continually make pilgrimages to Italy with students.

“It’s really like walking into living history over there,” he says.

O’Connell jokes that what really sealed the deal on Italy for him were the results of a survey. Italians were asked what was more important: Having a career or having lunch with friends? The verdict: sitting down to lunch with loved ones was far more important.

“That just tells you a lot about the people,” O’Connell says with a laugh. “It’s incredible!”

For O’Connell, the sketchbook, the process of drawing and watching and the final product are all about making connections: with people, with places and with oneself.

“Too much of life in our modern culture is based on randomness,” he says. “You just have to set aside time.”

His sketchbooks continue to fill: with drawings of pastries, branches, buildings, faces and landscapes. They are moments from O’Connell’s life, a life that is rich with curiosity and understanding. The hundreds of pages of his sketchbooks, filled with these moments, are a living, breathing history of his life and of his mind.

Categories:

One Sketch at a Time

July 12, 2010

One Sketch at a Time

0

Donate to Ethos

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Oregon - Ethos. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.