A century ago, Portland’s underground tunnels bustled with an illegal kidnapping trade. Or did they? Today, the truth behind urban legends blurs with the desire to believe.

Story by Christina O’Connor

Photos by Taylor Schefstrom

The crowd at Hobo’s Restaurant and Lounge in downtown Portland is dwindling. Most of the night’s patronage have moved on to more provocative pursuits across the street blares country music, and brave drunks stand up at the Boiler Room next door to slur their words in sloppy renditions of their favorite songs. But Hobo’s remains classy and inviting — a few parties linger at candlelit tables, sipping red wine, and chatting softly.

Below ground, it’s a different story.

Legend has it that from the 1840s until 1941, while Portland maintained a reputation as an upright city, illicit activity seethed in a series of underground tunnels — a seedy mélange of prostitution, gambling, and shanghaiing. Although mostly sealed off today, the tunnels apparently used to connect most of downtown. Intoxicated men from bars above would be dropped into the tunnels through hidden trapdoors. Once underground, the men were held in small cells until their kidnappers sold them to ship captains, forcing them to work onboard without pay. Some weren’t returned to Portland for up to six years, while others were never seen or heard from again. The practice came to be called shanghaiing because men would wake up in the middle of the ocean on their way to Shanghai, China. Today, the underground is said to be one of the most haunted places in the Pacific Northwest, crawling with the spirits of shanghaiers and their victims.

On the other hand, this could be nothing more than a scary story. An urban legend. Maybe it’s all just something that happened to somebody’s brother’s girlfriend’s cousin.

After all, there is not much left of the tunnels today. The area beneath Hobo’s and Old Town Pizza is one of the few spots where buildings still connect. Nobody has been able to track down anybody who was involved with the slave trade. Nobody has met anybody who helped construct the tunnels. And nobody has spoken with anybody who was shanghaied. But Cascade Geographic Society founder and director Michael P. Jones believes he has.

Most historians see the stories of the underground as nothing more than, well, stories. Apart from Jones’ sources, there is no direct connection or tangible proof to the allegations that circulate the streets of Portland. And without that proof, this is all just an urban legend — a modern narrative that has some documented aspects, such as a specific place and time, but is difficult to trace. Although nothing has been proven, people still cling to this story. It has become an integral part of Portland community legend. Tourists and locals alike come in droves to walk through the underground and bask in the debatable history. What is it that draws people in?

Staggering to the back corner of Hobo’s, Jones struggles to perch himself up on a high stool sandwiched between pool tables and video games. It’s the only place he can manage to sit after his recent foot surgery. “The doctor said that I wore out my bones,” Jones says. “He had never seen anything like it.”

Jones has been working in the underground since he was seven years old, trying to salvage artifacts from the past. Shoes. Shards of glass. Tin cans. These, he says, are all proof that shanghaiing happened. Because the underground today is difficult to access, rescuing these items is a tremendously difficult task. But Jones carries on, bad foot and all, because he says it’s important to preserve this part of Portland’s history.

Everyone in Hobo’s seems to know Jones. Servers wave as they rush back and forth taking orders and bussing tables. He grants them a nod and continues talking. Everybody who is affiliated with the area beneath Hobo’s seems to know Jones, too. Jones says that he has talked with primary sources — families of the shanghaied and the shanghaiiers. Over the years, various people have tracked Jones down to tell him their stories about the underground.

A young man weaves over to the table, fixated on Jones. “I know you, man!” he says, beer in one hand and propping himself up on the table with the other. He tells Jones that he took the tour a few years ago. “Is this place really haunted?” the man asks. “I mean, did all that stuff really happen?”

That question comes up again and again. And while Jones is entirely confident that shanghaiing happened in the tunnels, others are skeptical.

Although he might not be happy about it, in a way Jones understands why others have differing views. He explains that Western culture places too much importance on what is written down in textbooks, what he calls “accepted history,” and too little faith in oral histories, or “unaccepted history.”

He asserts that the westernized shift away from a belief in folklore is dangerous. “Once you start taking the accepted history and ignoring the unaccepted history, you’ve lost a lot of history because . . . what you’re going to find in folklore is a lot of history that hasn’t been put on this other side for some reason,” Jones says, shifting in his seat. A group at the pool table cheers every time one of them makes a shot. Jones ignores the noise and leans in closer to the table. He explains that while Western societies have established a steadfast separation between accepted histories and folklores, other cultures see the two as he feels they are: interrelated.

“Like if you go to [Asia], and in a lot of Native American tribes, storytelling is so important,” he says. “And it doesn’t mean the story isn’t true. But for our culture in the U.S., we’ve ignored so much.”

For Jones, what he hears about the underground cannot be ignored. “I just have to tell these stories,” he says.

But former Oregon Historical Society (OHS) public historian Richard Engeman feels the legends are nothing more than just stories. “This is nothing but hearsay,” he says.

Engeman spent years researching the underground. After amassing piles of research, he has been unable to find concrete evidence to prove shanghaiing occurred in the tunnels.

“If there are any tunnels at all, show me one,” he says. “If there is any evidence of any kind that points to sailors being shanghaied, I’d like to know about it.” When Engeman started at OHS in 2001, he quickly discovered the underground was a topic of much interest within the community. People often questioned him about the tunnels and shanghaiing, so he started looking for historical evidence to support their stories. The first time he called the city’s archive center to inquire about zoning documents for the tunnels, he had to hold the phone away from his ear because the woman on the other end was laughing so hard.

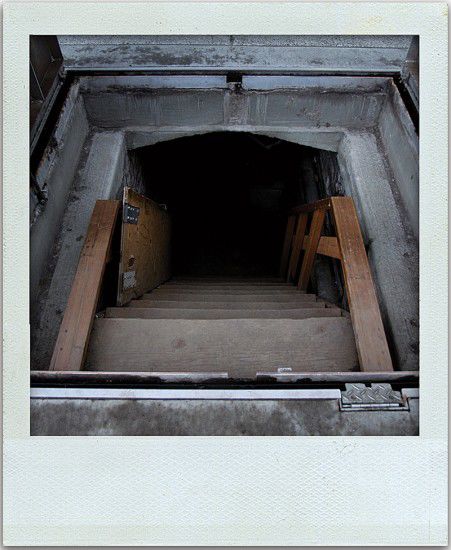

A couple weeks later and a block down, Portland Walking Tours guide Donna Yarborough leads a group of seven down the back stairs of Old Town Pizza. Yarborough, it seems, is the skeptic’s skeptic. Tunnels? No, she tells her group as they enter the basement, they would not be seeing any tunnels on this tour. She leads them to a brick corridor and tells them about the tunnels and shanghaiing, but denies that one has anything at all to do with the other. That brick corridor, she explains, which is no longer than ten feet, is all that’s left of the tunnels here.

Portland Walking Tours founder David Schargel maintains while there certainly were tunnels beneath the city, they had nothing to do with shanghaiing. Instead, the tunnels were built for a variety of purposes, including flood control and utility lines. He also explains that the tunnels were used to carry supplies to the docks — but none of these supplies included men.

Despite the lack of readily available evidence, these tales still persist throughout Portland. Many Portlanders grow up hearing about the tunnels. On a recent CGS tour, more than forty people crammed into the back courtyard of Hobo’s, listening as one of the tour guides delivered a well-rehearsed shtick about the tunnels, shanghaiing, and the very likely possibility that at least one person in the crowd would have a paranormal experience underground. The audience exchanged excited gasps and wide-eyed stares with one another.

“There’s a natural human impulse to be intrigued by tales of dark and mysterious and hidden things,” Engeman says. “That’s a fairly universal impulse, and the impulse to generate stories is also pretty universal. It’s not a mystery to me that somebody can take something and run with it until it becomes a whole other thread.” Engeman says some of the shanghaiing tales rumored to have happened in Portland have also been repeated in San Francisco, Seattle, and other port cities.

This sort of traveling localization is characteristic of urban legends. Many American teenagers have probably heard the one about the babysitter who realizes that the creepy phone calls she keeps getting are being made from inside the house. Or the one about the girl who finds her date hanging from the tree above the car. In Eugene, this story happened at Skinner’s Butte, explains Dr. Sharon Sherman, a folklorist at the University of Oregon. But in Los Angeles, the same thing happened at Mulholland Drive. In Honolulu, it was Morgan’s Corner. Not only do these legends transcend spatial limitations, but they have also recurred in various forms for generations. The one about the man who drives a mysterious girl home only to find that she has disappeared before they get there has been around since the horse and buggy days.

According to The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and Their Meanings, legends transcend time and space “not only because of their inherent plot interest but because they seem to convey true, worthwhile, and relevant information.” The book explains that urban legends often carry important lessons that reflect societal values and encourage an adherence to those standards. A terrible fate awaits those who do not comply.

Sherman has a simpler interpretation for the reason these stories are told and retold. “I think it’s just our fascination with the unknown,” she says. “Anything that’s unknown, people speculate about. And if they’ve heard it happened to someone else, there’s the question in one’s mind: ‘Could this really have happened?’”

Yarborough leads her group into another room in the basement under Old Town Pizza. Nothing resembles a tunnel, but it is dark and musty. Yarborough tells them to snap as many pictures as they can and hands them electromagnetic field detectors (EMFs). The pictures could pick up ghostly orbs, and EMFs, originally designed to find cables behind walls, are commonly used as ghost hunting tools.

Yarborough tells them to look for any sign of the spirit of Nina, a woman who was allegedly killed in the underground. The group wanders around the room, waiting for the light to change from green to red. When the color on the EMF shifts, it signals a change in the surrounding energy. This could mean that electrical wiring is nearby. But it also could mean ghost.

Today, although the same stories persist, Sherman speculates that the nature of urban legends is changing. Like Jones, she thinks people are becoming increasingly skeptical about these narratives today. A few decades ago, people used to accept the stories they heard as fact. But these days, hardly anybody takes urban legends seriously. “There’s no longer that same mystical feeling that I had when I was younger and that other people I knew had about those stories,” Sherman says.

She feels that this modern-day skepticism is partly caused by media saturation. The 1990s teen horror craze brought a series of movies about urban legends, while Web sites, like

Snopes.com, are dedicated to questioning these stories. “And so once people have seen the movies and read the information on the Internet, they no longer believe,” Sherman says.

But how does anybody really know for sure?

After unsuccessfully hunting around in the underground for ghosts, Yarborough and her group head to the White Eagle Saloon, a Portland hotel rumored to be haunted. By now, the group seems a little disheartened. They spent the light rail ride rolling their eyes at one another and barely suppressing their scoffs.

Upstairs at the hotel, Yarborough tells her group to keep their thumbs glued to their electromagnetic field detectors. Then she begins telling the story of Rose, a woman of ill repute, and Sam, a dim-witted piano player who worked at the hotel in the 1920s. When Sam, who had long been holding a torch for Rose, finally proposed, she laughed. Embarrassed and angered by Rose’s cruel reaction, Sam took her upstairs to his room — outside of which Yarborough and her group now stand. Rose and Sam argued, and when Rose emerged all she could do was stumble into the corridor — she had been stabbed. She died right there at the top of the staircase, where the group listens.

Right then, at the climax of the story, all electrical hell breaks loose — one of the EMFs starts going off. It turns orange, then red. A shift in energy. It could just mean electrical wiring. Or it could mean ghosts.

“Rose? Is that you?” Donna asks as she eyes the EMF. The tool turns back to the neutral yellow, then spikes up to red again. “Sam?”

By this time, it’s got everybody’s attention. The group leans closer, huddling together to watch the little meter go up and then down and then up again.

“Is that you, Rose?” Donna asks again.

The lights stop flickering.

Leaning toward the meter, the group waits. They wait for another spike, or any sign that Rose and Sam are trying to communicate with them. They wait, and for a brief moment, their full attention is focused on nothing but the lights on that little meter.

Just for that brief moment, some of the snide side-glances stop. The cynical under-the-breath comments end. For that brief moment, everyone just believes.

Categories:

Tracing Legends

May 31, 2010

Hidden tunnels, kidnapping, murder – urban myths lure tourists and locals alike to Portland’s Underground.

Tracing Legends

0

Donate to Ethos

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Oregon - Ethos. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.