Story by Jayati Ramakrishnan

Photo by Sumi Kim

Walking in the front door of Zany Zoo Pets means being greeted with both lively animal sounds and human chatter. Shrieks between Angel, the umbrella cockatoo, and Doodle, an African Grey Parrot; the scurrying of rats, hamsters, and guinea pigs mingle with the sound of delighted customers cooing over the cuddly-looking chinchillas and coatimundis. It also means getting slugged with the unforgettable pet store smell: musty, day-old wood shavings collected at the bottom of animals’ pans, the nutty smell of bird seed, and the sharp, salty air surrounding the rodents’ cages. The water animals swim in a huge metal tub that looks and smells like a pond.

Zany Zoo Pets, Inc. is a pet store in Eugene, Oregon that sells both common American pets like puppies, hamsters, and rabbits, as well as exotic animals rarely seen in pet stores. These include Maras, which are giant rodents that resemble small deer, as well as prehensile-tailed porcupines, common musk turtles, chinchillas, and a tiger reticulated python.

Customers could be greeted by the usual pet store sounds of whistling birds and scurrying guinea pigs. Or, they could be greeted with a ring-tailed lemur jumping on their shoulder to say hello. There’s no way to tell beforehand.

This particular lemur, Chester, belongs to the storeowner Nate McClain, and is not for sale. He keeps the company of many exotic animals that are available for purchase at the store. Owning exotic pets is an issue that tends to polarize animal lovers. Introducing nonnative animals to a new habitat causes concern for environmentalists because the animals could damage the ecosystem if they escape captivity. Some animal rights activists believe that exotic animals are not meant to be raised in captivity, and that their quality of life decreases when they live outside their natural habitats.

McClain is fully aware of the polarizing nature of his business. He follows some ground rules that keep the business within United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) laws, as well as a personal code of ethics. He gets animals from local exotic animal breeders, usually no farther than Seattle.

In an effort to procure his animals ethically, he follows a simple etiquette: “I do not do wild animals,” McClain says. “I appreciate the argument that wild animals are not meant to be pets, and I agree. I think it’s a huge transition for them.” Many of today’s exotic pets are offspring of wild animals that were captured for zoos several generations ago. A lot of the animals are now bred by hobbyists, whom McClain likens to comic book collectors. “A lot of exotic animal hobbyists have an encyclopedic knowledge of the animals they keep,” he says. “Which, even though they lack a degree, in my opinion makes them more qualified than people in zoos.”

McClain’s opposition to wild-caught animals stems from his desire to treat his animals properly, as well as his goal to educate the public about the exotic animal trade. Most people don’t realize how many animals in pet stores, including most reptiles, fish, and birds, are captured from the wild. “I don’t know many people who consider a canary or guppy to be exotic, but a lot of these animals are wild-caught.”

Kenneth Montville, College Campaign Director at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), points out that even when bred in captivity, some animals go through wretched treatment. PETA recently conducted an investigation of an intensive breeding facility in Southern California called Global Captive Breeders. The investigation revealed 600 snakes and reptiles living in horrific conditions. “Some people actually needed counseling after seeing the animals in this condition.” Montville recalls snakes regurgitating their food, something they only do when they have respiratory infections, and rats and mice drowning in barrels of water. This was the largest seizure of animals in California history, with a total of about 16 thousand animals rescued.

When these animals are taken away from the facility, a few things can happen to them. “Animals at the Global Captive Breeders in California were incredibly sick so animal control took them, and they were euthanized because of all the pathogens they were carrying. It was too harmful for other animals and other humans—way beyond repair,” Montville says. At another seizure in Texas, some of the animals were taken to various rehabilitation centers, and some were put in animal sanctuaries. It varies on a case-by-case basis.

While Zany Zoo works hard to maintain a high quality of life for all of their animals, it’s a lot of work and some individuals think there’s no way to truly give exotic animals a good home in an environment to which they are not native. Recently, the dichotomy of exotic pet breeding has spawned many debates across the country, especially in light of serious accidents involving traditionally wild animals. In Connecticut in 2009, a chimpanzee mauled a woman.

The monkey had been her friend’s live-in pet. Police came into the house and shot the chimp in an attempt to deter it, causing wounds that killed it. The case incited a national debate about raising wild animals in a domestic environment. The incident raised ethical questions, both about the treatment of the animal and the responsibility that their human caregivers possess. History shows that regardless of how well-trained animals are, they can become uncontrollable at any time.

Montville says that it’s impossible to really use the term “ethical” in the discussion of wild-caught and exotic animals. “The fact of the matter is we can’t even take care of our domestic animals. Every year, six to eight million cats and dogs are surrendered to shelter, and half of them are euthanized because they can’t find good homes—so bringing in more exotic animals is beyond irresponsible.”

McClain agrees with the idea that people need to have licenses and acknowledges the damage that can come from illegally bred animals. He feels that in some ways, the laws could be even stricter. “Unfortunately, you don’t need a license to own a coati (a South American animal related to the raccoon) – I think you should.” Oregon only outlaws animals that are potentially invasive and could cause damage to the ecosystem. This includes primates, crocodilians, wolf and cat hybrids over 50 pounds, and black bears. “If you don’t have the wherewithal or resources to own a chimp, there should be an outright ban.”

Montville feels that one of the reasons exotic pet ownership is such a problem is that the laws surrounding it are so weak. “Wildlife trafficking is an underground trade fueled by the exotic pet industry. The law is meant to combat it, but inspection is very scant.” He adds that budgets for inspection are tight, and that most governments do not consider animal issues a priority.

Zany Zoo has one exception to its “no wild-caught” rule: rescues. This includes everything from animals that people can’t take care of and want to find a better home for, to sick animals that Zany Zoo tries to revive. “We can at least do a good triage here, screen for parasites, and do injections,” McClain says.

McClain also hosts classes for elementary schools at his store and takes animals to local classrooms to teach students about certain types of wildlife. The Zoo also holds birthday parties in the store and operates a free petting zoo on weekends. He says that his goal is not only to educate the public about animals and offer people a good experience for animals they might otherwise fear, but also to show a paradigm of the exotic pet industry that actually works.

Oregon law requires citizens to obtain a USDA license to own an exotic animal if you have more than three breeding females. To get a USDA exotic animals license, a person must fill out paperwork and have a veterinarian assess the animal’s living space to make sure the person is fit to own it. In the case of a pet store like Zany Zoo, a veterinarian comes in once a year. The store also gets annual, unplanned visits from a USDA inspector.

Montville sees a lot of breeders who treat their animals atrociously and believes that the exotic pet industry is so closely tied to the illegal animal trade that it’s better to just avoid buying exotic animals at all. “These animals are not being sold out of care [for the animals] but for the money they’ll bring in. When animals are sold to make a profit, corners are cut, and the animals are always the ones that end up paying the price for that,” Montville says.

Zany Zoo has encountered some disgruntled animal rights activists, and McClain worries that their actions often hurt the animals. “We have had people come in here and open up the bird cages and try and shoo them out the door.” He says that this action, while not only exceptionally illegal, is also bad for the birds – most of them are tropical and cannot handle the temperate Oregon climate.

McClain acknowledges the opinion that animals should not be kept in captivity because they cannot handle the stress. However, while he believes that some animals do not make good pets, McClain thinks that certain aspects of animals’ lives are better suited for captivity. “Animals are not devoid of stress in their natural life,” he says, adding that as the dominant species, humans have a skewed, somewhat softened idea of how animals function in nature. “A sugar glider in the wild has a couple imperatives: find food, don’t be food, and procreate. Everything else is stress.” In captivity, he says, all of those stressors are removed. “So the idea that animals can’t handle the stress of captivity is ridiculous. You just have to do it slowly.”

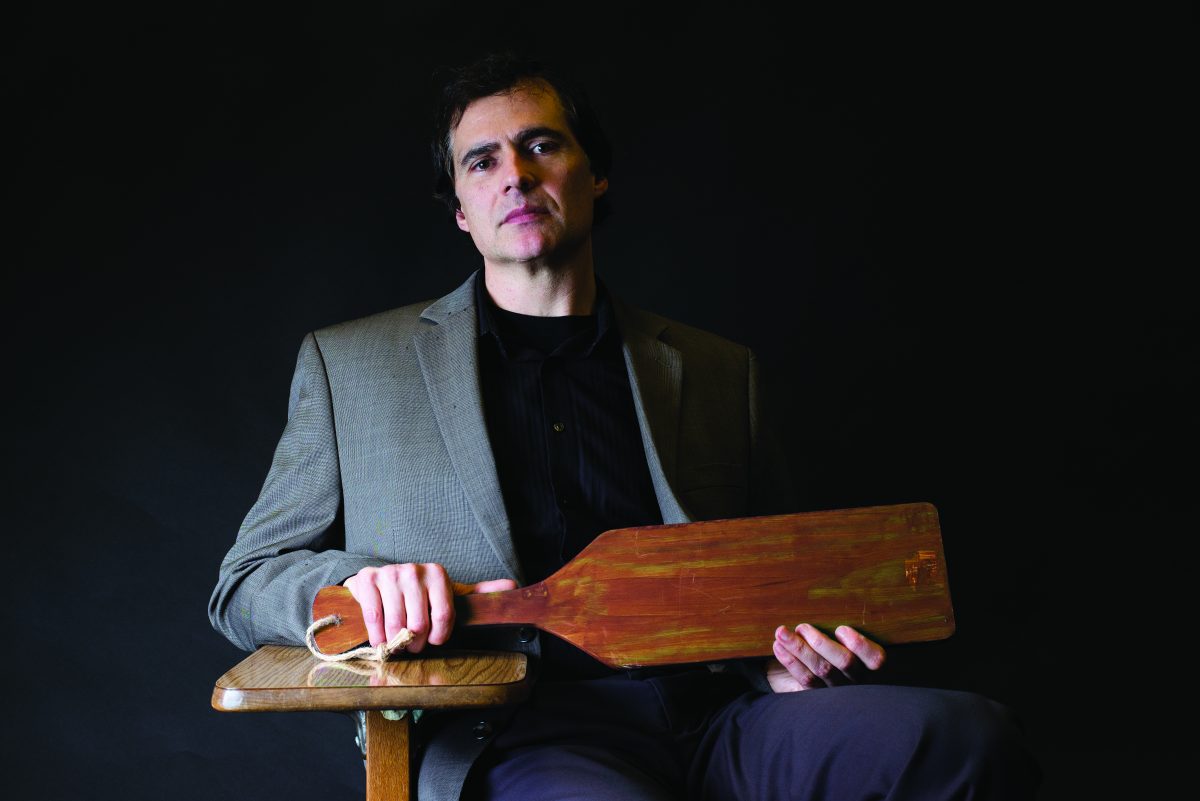

Jeff Todahl, Director of the Center for the Prevention of Abuse and Neglect and Associate Professor in the Couples and Family Therapy Program at the University of Oregon, reflects upon his personal childhood experiences of physical punishment throughout elementary school, including paddling and pinching from teachers.