“I’m scared,” John says, slipping in and out of consciousness.

John is in his mid-sixties, suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema, and he’s on his deathbed. Amy May is sitting next to him, trying to find the right words to bring him the peace that he needs.

“I hear that you’re scared,” she says. “But I’m here with you. You are not alone.”

A Willie Nelson song plays softly in the background, filling the silence in John’s temporary housing unit.

May and John, who Ethos is referring to because he was unable to give consent to be referred to by his full name, had known each other for about a year. During that time, she’d spent countless hours helping him work through the trauma he’d experienced during a life full of homelessness and addiction. He had been in hospice since before he met May, and while his caregivers were helpful, he told May they did little to help ease his loneliness and anxiety about death.

May is a death doula, a type of counselor who provides mental, spiritual and emotional support to the dying and their families. Through her work, she has helped dozens of people like John find peace at the end of their lives.

During their twice-weekly visits, May and John worked together to process the emotions that were bubbling to the surface as he got closer to the end and developed a plan for how he wanted his final days to go. As a fan of old-school country music, John made sure that Willie Nelson and Hank Williams were a part of that plan.

He died that night, a few hours after May left his facility. But she says she thinks the day she spent at his bedside made all the difference.

“I sat there with him, I held his hand, chatted with him about the day,” she says. “And I was grateful. I am so privileged to be with people at this part of their journey.”

Amid a rapidly aging U.S. population and an increasing demand for end-of-life care, the coronavirus pandemic forced death doulas like May to adapt to an often uncomfortable remote work environment. And with 3.7 million dead from COVID-19 since the pandemic started, death is on many people’s minds. Like no other event in recent history, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of end-of-life workers.

Death doulas say the pandemic has led to an increased demand for their services ― particularly in families who lost loved ones to COVID-19 ― and higher enrollment numbers in death doula training programs. The International End-of-Life Doula Association, a nonprofit that provides a comprehensive death doula training course, saw a 29 percent increase in enrollment in 2020 from 2019, according to its operations and training division.

“We’re selling out months in advance,” says Shelby Kirillin, a Virginia-based death doula and a trainer with the association. “It’s quite startling to see the uptick in people wanting to be trained as a doula.”

Kirillin, who worked as an ICU nurse before becoming a death doula, sees the increased interest in death doula work partially as a result of the pandemic sparking conversations about death. But the shift toward more supportive end-of-life care began with the birth of the hospice industry in the 1970s.

Hospice care is available to terminally ill people with less than six months to live and involves a team of healthcare professionals providing medical care and symptom management meant to improve quality of life, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Association.

The first hospice agency in the U.S. was founded in Connecticut in 1974, and since then, the number of hospices and end-of-life workers has increased dramatically. Now baby boomers, a generation born between 1946 and 1964 that makes up 70 million people in the U.S., are starting to die of old age, and are increasing demand even further for hospice services.

According to a 2020 report by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, there were nearly 1.6 million Medicare-insured people receiving hospice care in the U.S. in 2018, an increase of 4 percent from 2017. In a 2015 report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that the number of people receiving hospice care increased by seven times from 1990 to 2013 and that the number of hospice providers tripled during that same time.

But while hospice workers can provide medical support to the dying, they often deal with multiple clients at a time and are unable to offer the same level of emotional and spiritual support as death doulas, Kirillin says. She says her friend, who works with 30-40 clients at a time as a hospice social worker, says she wishes she could do more to support them emotionally but feels limited by time.

“I think that’s why end-of-life doulas are becoming a thing,” Kirillin says. “It’s this generation, the baby boomer generation, that now is dying. And they’re seeing how we treat death and being like, yeah, no. There’s more to death than just medicine.”

Hospice can also fall short in its often restrictive eligibility requirements, Kirillin says. To qualify for Medicare-insured hospice, a person must have a prognosis of six months to live or less. Some hospices also require that the individual not be receiving treatment, meaning that terminally ill people with less than a year to live don’t always have access to the support they need.

“There’s people that, let’s say, have metastatic cancer everywhere, that are doing radiation and chemo,” Kirillin says. “They know they’re dying, they know that they have less than a year to live, but because they’re going through those treatments, they are not eligible to go into hospice.”

There has been a documented need for higher-quality end-of-life care since long before there was an established death doula community. In a 1995 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a team of physicians from around the country identified significant shortcomings in communication between terminally ill patients and their doctors.

The observational study took place at five major U.S. hospitals over four years and found that only 47 percent of the doctors surveyed knew when their patients wanted to forgo CPR. Similarly, 46 percent of all do-not-resuscitate orders were written within 48 hours of the patient’s death, and family members surveyed reported high levels of physical and emotional discomfort in their loved ones in the days leading up to their deaths.

According to Kirillin, death doulas have existed since long before there was an established community or professional training programs. But since the emergence of the first professional doulas through the founding of the International End of Life Doula Association in 2015, the field has exploded in popularity.

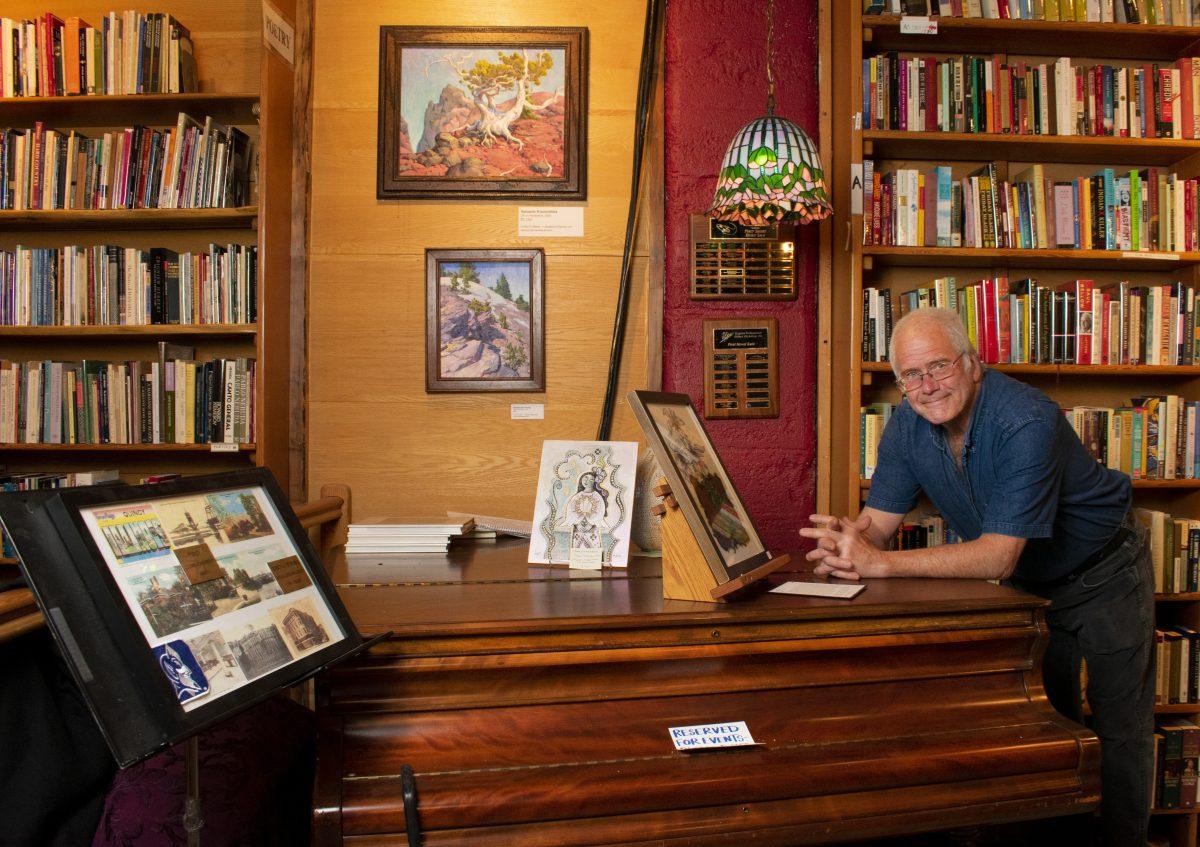

May, who started working at Eugene’s White Bird Clinic as an intern in 2017, is now the clinic’s only death doula. She created the position after meeting John and realizing there was a need for personalized end-of-life counseling in Eugene, particularly for those who are unhoused or suffer from substance abuse issues.

May says she takes a client-centered approach to her work, so what she does changes depending on each person’s needs.

“What I hope to do is show up and provide some comfort and support and really be with that person and help them be with themselves,” she says.

Like many death doulas, May had to see the majority of her clients remotely over the past year.

For her clients whose minds and bodies are quickly deteriorating, it is nearly impossible to arrange a Zoom meeting without help from a caregiver, meaning that only those who were living in a facility or had help from hospice could see her virtually.

And even then the process can be challenging, she says. Discussing intensely emotional topics, like life regrets and death anxiety, through an electronic device can be too much for someone who already has difficulty hearing and communicating clearly.

In the spring of 2020, as tens of thousands of Americans were dying from COVID-19 each week, the number of referrals May got from hospice agencies dropped significantly, meaning she did not receive any new clients. She says one client was referred to her but cut ties after a failed attempt at an online consultation.

“It was hard for the person to hear me and understand,” she says. “They weren’t able to sit up and communicate clearly. And this is a really sacred, delicate, precious conversation. To do it over the internet takes away from that experience.”

Local hospitals closed their doors to visitors when the pandemic hit, meaning that May also had limited access to some of her existing clients as they got close to the end. She was working with two homeless men who were hospitalized right before their deaths, and she couldn’t be there to guide them through their final moments.

“That breaks my heart,” she says. “I feel sad that I couldn’t be there with them.”

Pennsylvania-based death doula Jamie Eaddy, a colleague of Kirillin’s at the International End of Life Doula Association and the organization’s Director of Program Development, says that much of her job involves going over plans with her clients and working with families to commemorate their loved ones in what Eaddy calls a “legacy project.” While COVID-19 restrictions have complicated this process, Eaddy and her clients have found creative ways to adapt.

“When I’m working with families, I try to help them use their imagination, especially during the times of social distancing,” she says.

She recently worked with the 91-year-old matriarch of a large family who was bedridden in her home, slowly succumbing to COVID-19. The woman had four adult children, all of whom had children of their own. But only one could be present with her during her final days due to the possibility of viral exposure. In her prime she had been known for her cooking skills, so Eaddy suggested that the siblings put together a book of their mother’s recipes and eat one final meal together over a Zoom call.

It took some planning. The eldest child, who was also the designated caregiver, had to gather all the recipes together, which were scattered throughout the house on notepads and index cards, and give them to one of the grandchildren, who then brought the finished book to the other siblings.

The family cooked and ate Mom’s famous mac ‘n’ cheese together over Zoom from their respective homes, laughing and reminiscing about their childhood, all while she watched from her deathbed. By this point, she was no longer eating or talking, but Eaddy believes she knew what was happening.

“She wasn’t giving us much more than an occasional smile,” she says. “But depending on your beliefs, I believe she was still experiencing some of what was taking place.”

While death doulas frequently work with the elderly, Kirillin and Eaddy say they also work with many younger people facing death.

Kirillin says she worked with a 27-year-old woman with two young children who had an inoperable brain stem tumor. She hosted a Zoom event for the woman and all her closest friends in what Kirillin called a “circle of love ceremony” — a living eulogy where everyone lit candles, ate food together and told the woman how much she meant to them.

“It was sad, it was happy, it was funny,” Kirillin says. “It was real life. And everything in between.”

She says the mean age of her clients is 40-60, and she believes that if anything good will come out of the pandemic, it will be an increased cultural awareness of the importance of end-of-life planning.

Through their work with the doula training program, Eaddy and Kirillin have noticed a substantial shift in the demographics of the people registering for their courses. According to Eaddy, there were far more young people signing up for the association’s training program in 2020 than in years past, something she and Kirillin say they believe is at least partially due to the pandemic.

“So many people think, ‘Oh, yeah, death will happen when you’re like 80 or 90,’” Kirillin says. “But I think hearing about people dying throughout the age spectrum is an eye-opener to people. It really brought mortality to the forefront like nothing ever has for this generation.”

Before the pandemic, May was one of only a handful of death doulas working in Eugene. But with the pandemic sparking new conversations about death, the doula community has grown locally as well as nationally.

Mandy Gettler works in the University of Oregon’s Innovation Partnership Services and volunteers with local hospices. She says death never bothered her, and she felt drawn to a career in end-of-life counseling ever since she lost her older brother to a terminal heart condition as a child and witnessed how unprepared her family was for the loss.

At the onset of the pandemic, Gettler had just completed her training with the International End of Life Doula Association and was flirting with the idea of starting her own death doula business, having provided informal end-of-life counseling to friends and family members in the past. But she says the conversations about death that the pandemic brought up and the extra free time it gave her made her realize it was time to start her own practice.

“It just kind of all aligned,” she says. “This is my one opportunity to take some time off and rest and figure out what I want to be when I grow up.”

Through her practice, End of Life Doula Services, Gettler offers personalized end-of-life support to her clients. She uses guided imagery, meditation, emotional support and extensive planning to help her clients and their loved ones cope with grief and death anxiety. Gettler has not yet taken any clients, but she’s working to advertise her services to the community and has hosted events meant to get people thinking about their end-of-life plans.

“I can’t think of another time in my lifetime, or even in my parents’ lifetime, where everyone from all walks of life were so affected by death and dying,” she says. “But there’s some agency in that. I’m not dead yet. I get to make choices. I can start making plans.”

Along with an increased interest in death doula work, 2020 also saw an increase in the number of people utilizing Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act ― a piece of 1997 legislation that allows individuals with less than six months to live to take a lethal dose of prescribed medication with physician approval.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, 2,895 people have received prescriptions since the act’s inception, and in 2020, there were 370 prescriptions written, compared to 297 in 2019.

Susan Smith is a volunteer coordinator for End of Life Choices Oregon, which is a Portland-based nonprofit working to help people navigate the act. She says that while community outreach and increased awareness of Death With Dignity likely played a role, she believes the uptick in prescriptions can also be attributed to the pandemic and other challenging events of the past year.

“Between the politics and COVID-19 and the fires and climate change, we’re really being bombarded by challenges all the time, and it’s stressful,” she says. “And when you’re sick, and you’re going to die anyway, some people might have said, ‘Okay, I don’t want to stick around for the rest of this.’”

Smith and her volunteers partner with doctors and work closely with death doulas to ensure their clients have everything they need to make the transition smooth. She says they are often present when their clients take the lethal medication, but that it all depends on the dying’s wishes, and that sometimes, they would rather be alone during their final moments.

“We’re kind of coaching them on how to take this very bitter medication,” Smith says. “And it all needs to be ingested before they fall asleep. So we’re death coaches, kind of like the doulas.”

In September, at the height of the devastating wildfire season that laid waste to parts of rural Oregon, she visited a man who was dying of cancer and had decided to use Death With Dignity to end his life. He lived in an isolated community in the heart of a fire evacuation zone. His neighbors had fled, but the man wanted to die at home, so Smith, his doctor and a few of his hospice caregivers suited up in their personal protective equipment – protecting them from both COVID-19 transmission and the wildfire smoke – and made the journey as the sky above glowed orange and ash fell like snow.

“There was music on. It was very beautiful,” she says.

Death is hard for most people to talk about, but May, Gettler, Kirillin, Smith and Eaddy say the best way to ease people’s anxieties is to normalize conversations about the dying process. They recognize the fear and intense emotions that accompany it but encourage people to see it as a normal part of life that can be just as beautiful as birth, especially at a time when mortality is so present in people’s minds.

“I think anger and sadness are both responses to pain and fear,” Gettler says. “And what can be more fearful than something that you never get to practice? Nobody gets to practice dying.”

Death will always be sad, Kirillin says, but the best way to make the process easier for both the dying and their loved ones is to recognize the inevitable and start preparing before it’s too late.

“I think it’s a survival instinct in humans,” she says. “We will fight until the end because we don’t want to die. But so far, mortality is still 100 percent, no matter what medicine has thrown at us.”

For May, every client’s death is sad. She says she feels grief for all of them, but more than that, she feels privileged to be able to share such an intimate moment of their lives.

With John, she says the gratitude was mutual. The last time she saw him, she was sure to make that clear.

“I thanked him a lot that day,” she says. “Thank you for letting me be part of your life. Thank you for allowing me into your world. Thank you for trusting me with your story. It’s been such an honor to be here with you through it.”

“I am most grateful for the trust extended to me by clients to walk the path with them, even for a short while. I love witnessing the profound love human beings are capable of sharing,” says May. “Death can open windows to personal power, understanding, and inner knowing that we might have thought weren't possible. I absolutely love talking to folks about these personal insights and transformations.”

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)