Trevor Walraven was sentenced to life in prison in 1998, at 14 years old. He was tried as an adult on an aggravated murder conviction. Walraven says for the first 13 years of his incarceration, education was far from his top priority. Even if he wanted to, he says there weren’t good educational resources he could get involved with.

Walraven bounced around several different facilities in Oregon, both juvenile and adult. But he spent the bulk of his time at Oregon State Penitentiary, a maximum-security prison in Salem, starting in 2004.

“I very much lived on the inside,” Walraven says. “I developed a career while I was there and I didn’t know if I was ever going to get out.”

He had a job in the maintenance department in the laundry room in the prison. Trevor decided to learn everything he could to make that job a career.

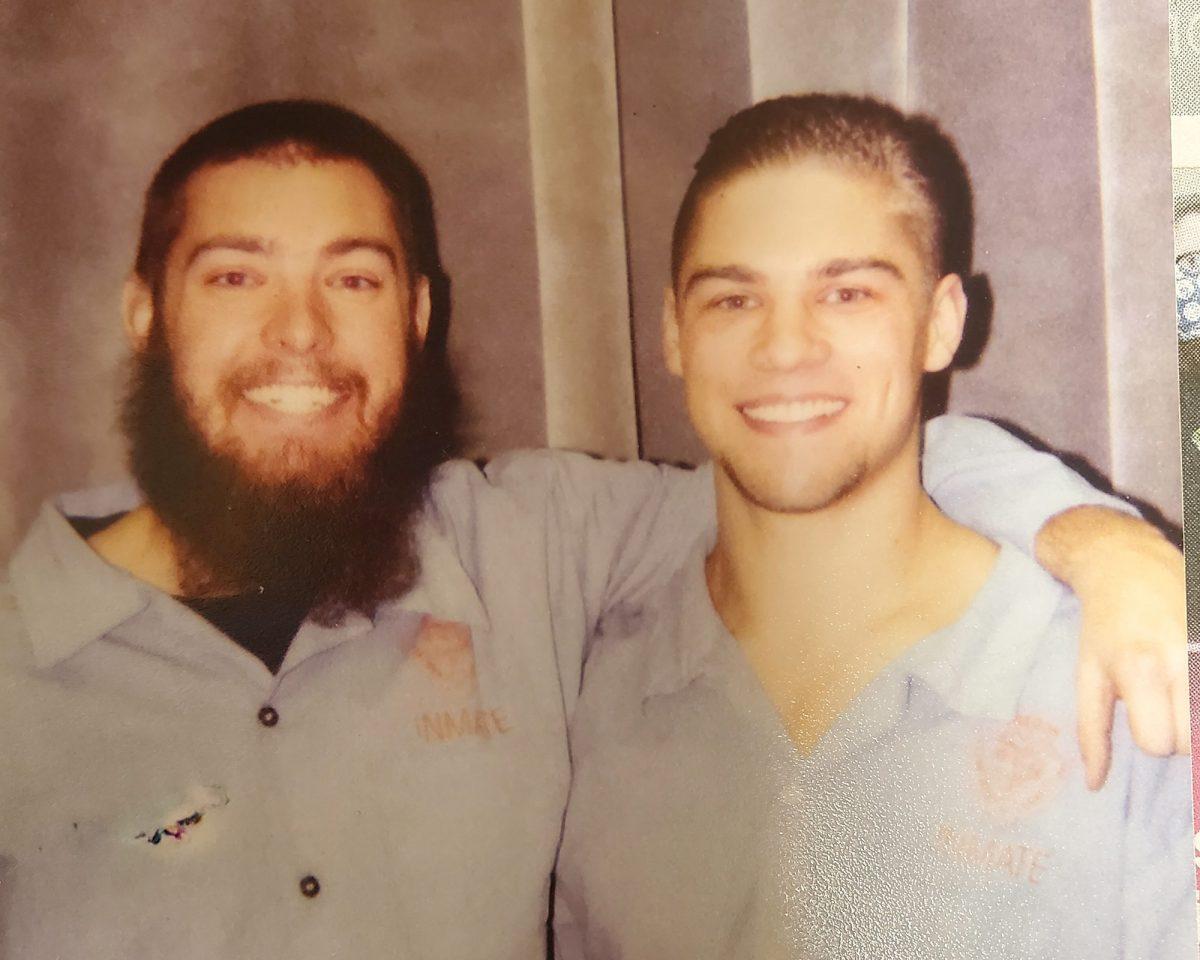

Walraven and his brother were both incarcerated at Oregon State Penitentiary. They lived and worked together. Walraven’s brother attended the University of Oregon before his incarceration, and he started taking Inside-Out classes in 2011.

The Inside Out Program brings together two groups of people with different life experiences — incarcerated people and students from four-year universities. The University of Oregon is one of over 150 colleges and universities around the country that facilitate Inside-Out classes with their local prisons. The classes provide an opportunity for the students to take higher education classes together and learn from each other as people with different lived experiences and life circumstances.

The program helps incarcerated people get an education behind bars, which helps them find a greater sense of self-worth and for some, envision potential lives outside of prison. This can sometimes help people stay out of prison once released. According to a report by the RAND Center, 40% of formerly incarcerated adults are reincarcerated within three years of release. The study found that when incarcerated people participated in education programs, the rate of recidivism reduced by 43%.

Currently, only Oregon State Penitentiary and Oregon State Correctional Institution offer upper-division university classes to incarcerated students. However, a variety of not-for-credit educational opportunities are also offered at the 14 prisons around Oregon, like book donations, book discussions and educational TV programming.

These not-for-credit programs, through the Prison Education Program, provide incarcerated people an opportunity to learn without the added pressure of for-credit programs or learning with other college students. The leadership of incarcerated students pushed to make these options available and many students who start by taking not-for-credit classes end up taking for-credit classes, says Katie Dwyer, the Coordinator for the Prison Education program at UO.

The first for-credit classes in the women’s prison, Coffee Creek Correctional Facility in Wilsonville, Oregon, will be offered to start this summer, Dwyer says. The program at UO currently offers classes at Oregon State Penitentiary and Oregon State Correctional Institution.

To date, the Inside-Out program through UO has served 800 incarcerated students and 800 students who aren’t incarcerated in 62 different classes, according to Dwyer. Worldwide, 150 different higher education institutions run an Inside-Out program, serving over 60,000 students, according to the Inside-Out Program official website.

At UO, most funding comes from specific departments and the Clark Honors College. Dwyer says the UO Foundation, the Office of the Provost, individual donations and the Associated Students of the University of Oregon are some of the major donors

Walraven’s brother encouraged him to take classes through the Inside-Out program because it had been such a transformative experience for him. Walraven was hesitant at first.

“I just didn’t think that I could fit in, that I could learn alongside students,” Walraven says. “So there was a lot of anxiety, a lot of questioning my ability.”

In 2011, Walraven took his first Inside-Out course. Within the first half of the term, the professor asked Walraven to help facilitate the class the following year because of his level of engagement and his leadership skills.

The program prioritizes people-first language, referring to university students as “outside students” and the students who are in the prison as “inside students,” to recognize the peer relationship between all of the students, says Ellen Scott, a professor of sociology at UO who teaches classes on the inside. The program could have chosen to differentiate participants as “students” and “inmates” but Scott says this defeats the purpose of the program, which works to humanize all people and recognize that both parties are students of the university.

When students from UO walk into a prison, they are required to walk in a single-file line in alphabetical order. No talking too loud. No running. They pass through a series of checkpoints, the doors locking behind them as they advance. Students are forbidden from wearing blue or jeans because people inside Oregon prisons wear blue.

Walking through the metal detector at Oregon State Correctional Institution, Bianca, a current intern at UO’s Prison Education Program, remembers watching students try a variety of methods to make it through without setting off the alarm. Covering up a button, slowing down, going in sideways — students were not allowed into the prison until they successfully passed through the metal detectors.

Due to the semi-anonymity rule of the program, inside and outside students only learn each other’s first names. To stick with this rule, the program asked that students in this article be referred to by their first names only. Walraven is an exception to this rule because he is open with his story in the work he continues to do for the program and was okay with his last name being shared.

Both inside and outside students can apply to be interns. This involves helping to lead classes and sometimes providing support for both inside and outside students.

Once the students pass through the security checkpoints, they join a room full of incarcerated people for class. The classes meet once a week for 10 weeks, and the program offers college credit to both inside and outside students.

Each Inside-Out class consists of 10 to 15 students from inside the prison and 10 to 15 UO students from outside the prison. They collectively sit in a circle, and the classes are mostly discussion-based.

The classes are open to all inside and outside students, but they must complete an application and an interview before being accepted.

“There’s a tremendous sense of excitement before each class,” Walraven says. “A sense of challenge, a feeling of hopefulness, a sense of gratitude for the opportunity to be in a room with other individuals who are willing to just kind of see past everything and look to who an individual is today.”

“Wagon wheel” is a traditional ice breaker for the Inside-Out program, according to Walraven. An inside circle of chairs faces the same number of chairs on an outside circle. Students from UO sit on the inside circle, and incarcerated students sit on the outside circle.

The professor asks a series of ice breaker questions, starting simple: If you had a superpower, what would it be? If you could be any animal, which one would you choose? The professor then progresses to questions related to class content. After every question, the outside ring rotates so that by the end, every outside student has talked to every inside student.

Though Walraven was anxious in these classes at first, the Inside-Out classes became a formative part of Walraven’s last few years in prison. The anxiety lifted for Walraven after his first few classes, and he was able to experience the humanizing nature of the program. His fear of not fitting in was replaced by a feeling of excitement before each class.

“All outside students knew that we had done something that was arguably deservable of incarceration,” Walraven says. “Having conversations with students that were in ways vulnerable, but ultimately just super neutral, non-judgmental, very humanizing conversations around everything under the sun, that in and of itself was transformative.”

Julie, a former intern, knew that the Inside-Out class would change them. Their father was incarcerated and Julie says being in classes with inside students and hearing their stories brought a new lens to view their father’s story with.

“Folks would talk about their own experiences being in solitary confinement, and my father was in solitary confinement,” Julie says. “Hearing folks tell their stories really just brought a different dimension to that lens because my dad never told me what it was exactly like being in solitary.”

After taking an Inside-Out class, Julie became an intern for the program.

“I just want to make a note that this is not like, an anthropological learning about people,” Julie says. “This is learning with, struggling with, learning together. Each of us being a teacher for one another — through our stories, through struggling with the material.”

Walraven remembers a sociology class he took where the professor said, “once you know, you owe.” That line stuck with him and helped Walraven to recognize his responsibility to the community and to the people he had harmed.

“I was someone who had not taken responsibility for my actions that led to incarceration,” Walraven says.

Walraven is not the only student from the inside who had a meaningful experience in the program. Shawn was incarcerated at 18 years old. He started taking Inside-Out classes in 2007, when he was 31 years old, at Oregon State University while inside the Oregon State Correctional Institution. He ended up being an intern for the program.

“The courses were humanizing,” Shawn says. “To look at us not just as the worst act or our crime, but to see us first as humans, that’s very healing for a prisoner, because as a prisoner, you are ostracized.”

Shawn says the experience was socially transformative because it was a chance to interact with people who had different lived experiences from the people inside the prison. Those few hours in an Inside-Out class with students from the university felt like being outside of prison, Shawn says.

Shawn graduated with a degree in humanities from UO in 2019, the first student from inside the prison that was able to do so because he already had an associate’s degree and spent over a decade taking classes and working toward his bachelor’s degree through the Inside-Out program. In July 2020, Shawn was released from prison. He is currently in grad school at UO for Prevention Sciences, which he can do because he got an undergraduate degree through the Inside-Out program while incarcerated.

Shawn says Prevention Science is a social work and research program that focuses on negative health outcomes. Shawn focuses on “juvenile and emerging adult development as it relates to delinquency.”

“The classes provided me access to education,” Shawn says. “Prisoners that receive education recidivate at a much lower level than prisoners who don’t receive education.”

While getting people degrees is a bonus of the Inside-Out program, the overall goal is to get inside students involved and excited about education, Dwyer says. She says all seven people who’ve gotten degrees from inside the prison already had associate degrees.

Dwyer says inside students can only take up to two classes per term, but students are not guaranteed to get into a class or have options of classes they have not taken. Similarly, the 1994 Oregon Measure 17 requires that all inmates work full-time while incarcerated in Oregon. Education doesn’t count toward those 40 hours a week. This means it takes a long time for students to earn a degree if that is their end goal.

Walraven calls the Inside-Out program his “aha moment,” prompting his leadership and involvement in programs such as Inside-Out and the “lifers club” within the prison for the last five years of his incarceration. The “lifers club” is a group of incarcerated people who are serving long sentences, mostly for homicide cases. Walraven served as the president of the club and acted as the liaison between the club and prison faculty.

“Through the Inside-Out class, I recognized that I had potential that I wasn’t utilizing,” Walraven says. “Seeing others value my voice just gave me a different perspective.”

While outside students have the luxury to do their coursework anywhere — on the main lawn at UO, on a plane traveling home, in a coffee shop — inside students are confined to a seven-by-eleven-foot cell, doing the same work.

“They are sitting in a cell, they have very few windows, they don’t have a choice of where they go, and they haven’t moved their body by more than one mile in decades,” says Emily, a former Inside-Out intern. “Realizing that was dizzying to me. It made me so uncomfortable and really struggle to handle or process the freedoms I had.”

The process of leaving the prison after the Inside-Out class is mostly the same as entering: a series of checkpoints without needing to pass through a metal detector. But as the outside students and faculty leave, they are barred off from classmates. And when outside students are not at the prison in classes, they have no contact with the inside students.

One of the main rules of the Inside-Out program is that outside students and faculty are not allowed to stay connected once the classes are over.

According to Dwyer, most Departments of Corrections around the country require that volunteers in the prisons do not stay in contact with incarcerated people except when they are in person for specific volunteer opportunities. The national Inside-Out program enforces this protocol through the semi-anonymity in only knowing first names and the no-contact rule, which forbids students from staying in contact after the classes finish.

Dwyer attended the first Inside-Out class at UO in 2007. She remembers it being hard to not form lasting relationships.

“It was really, really hard to know that I was heading out for summer break,” Dwyer says. “And then to know that some of the people that were in that class were serving life sentences.”

Over the past year, Inside-Out and the larger Prison Education System have drastically changed as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic. The classes offered to inside students are taught completely through the mail.

Dwyer is hopeful that starting next fall, Inside-Out classes will be able to meet in person again.

Many of the current and former outside interns express the importance of this program in shaping their future career goals. The former inside students, Walraven and Shawn, are both still involved in the program as trainers and speakers.

In 2016, Walraven was released from Oregon State Penitentiary after years of not knowing whether or not he would ever get out. After his release, Walraven co-founded the Youth Justice Project and helped the passage of Senate Bill 1008, changing the way youth are tried in Oregon by reversing the waiver mandate that allowed youth 16 to 18 to be automatically tried as adults.

Through his leadership on the inside, Walraven helped push to make Inside-Out classes and programs through the larger Prison Education Program accessible to almost everyone in the prison.

“Our program would not be what it is without people like Trevor,” Dwyer says.

While hesitant at first, Walraven ended up taking as many Inside-Out classes as he could. Although no longer incarcerated, Walraven is still very much involved with the Prison Education Program. He has helped coach future Inside-Out facilitators, spoken to Inside-Out classes around the country and continues to help with planning for the future of the Prison Education Program.

(Left) Walraven stands next to his brother, Josh (right), in OSP while they were both incarcerated. Trevor says his brother, who started taking Inside-Out courses around 2008, was one of the reasons he took his first class in 2011. (Photo Courtesy of Trevor Walraven)

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)