Blockbuster Video had 65 million registered customers in the late 1990s. Its blue-and-yellow movie ticket sign hung on 9,000 stores across the country. But only a decade later, the business began to fail with the rise of online streaming services like Netflix.

The company filed for bankruptcy in 2010, but one last Blockbuster remains in Bend, Oregon, and is run by a family who cares deeply about the store’s continuation. Ironically, viewers can now watch a documentary about the last Blockbuster on Netflix — the streaming service that put the company out of business in the first place.

This story isn’t unique to movie rental shops. All kinds of brick-and-mortar businesses across the country fell to the rise of the digital age. When Pew Research Center conducted a survey in 2000, only 22 percent of Americans said they had made an online purchase that day. In 2016, that statistic jumped to 79 percent.

Brick-and-mortar businesses selling products like books, pornography and music have been going out of business across the country with the emergence of online competitors like Amazon, Pornhub and Spotify in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t made anything easier for brick-and-mortar businesses with constantly changing business restrictions imposed by federal and state governments and a huge shift toward a more digital economy. In 2020, over 12,200 brick-and-mortar stores were forced to permanently close, according to a Forbes report.

Many bookshops, DVD porn shops and music stores, among other brick-and-mortar businesses, have closed during the pandemic. But small businesses Tsunami Books, B&B Distributors and House of Records in Eugene, Oregon, have managed to survive as some of the last businesses standing in their respective industries because of community members who still value buying goods in real places, from real people they can see, talk to and support.

Tsunami Books:

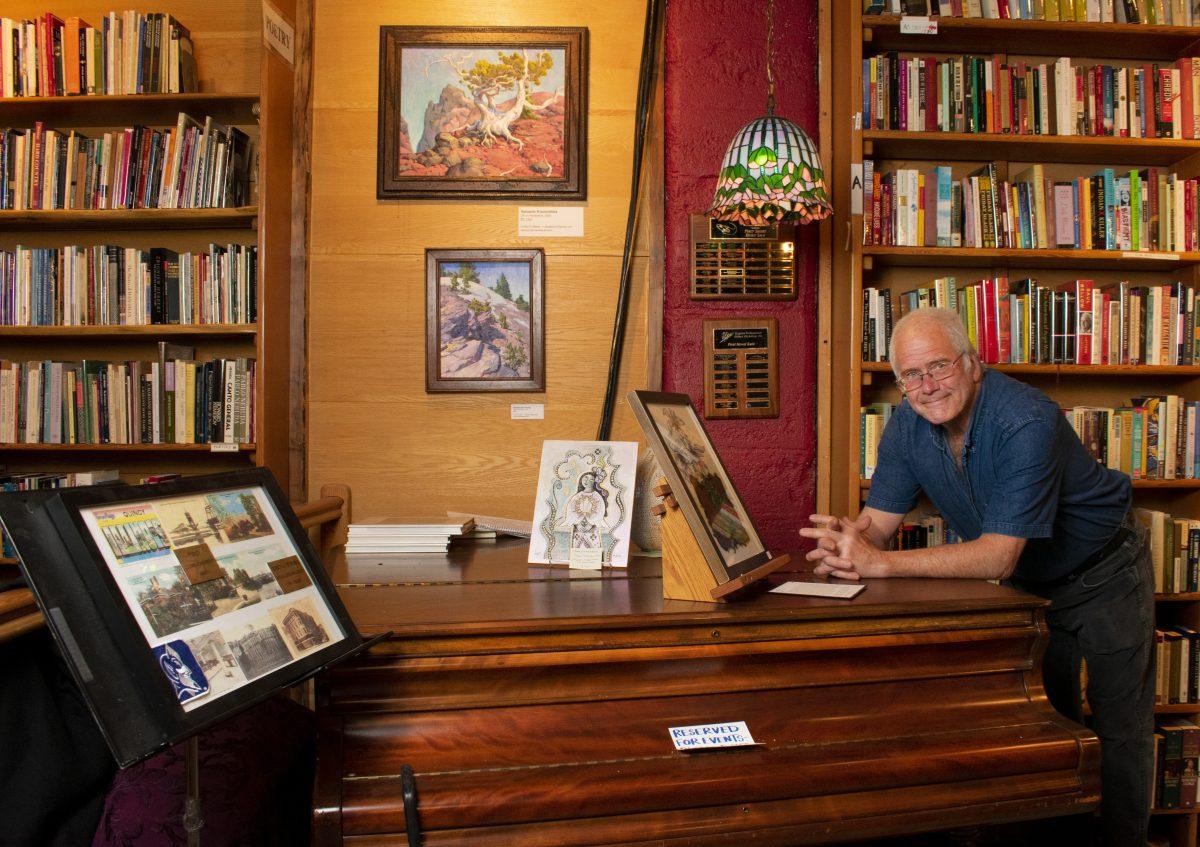

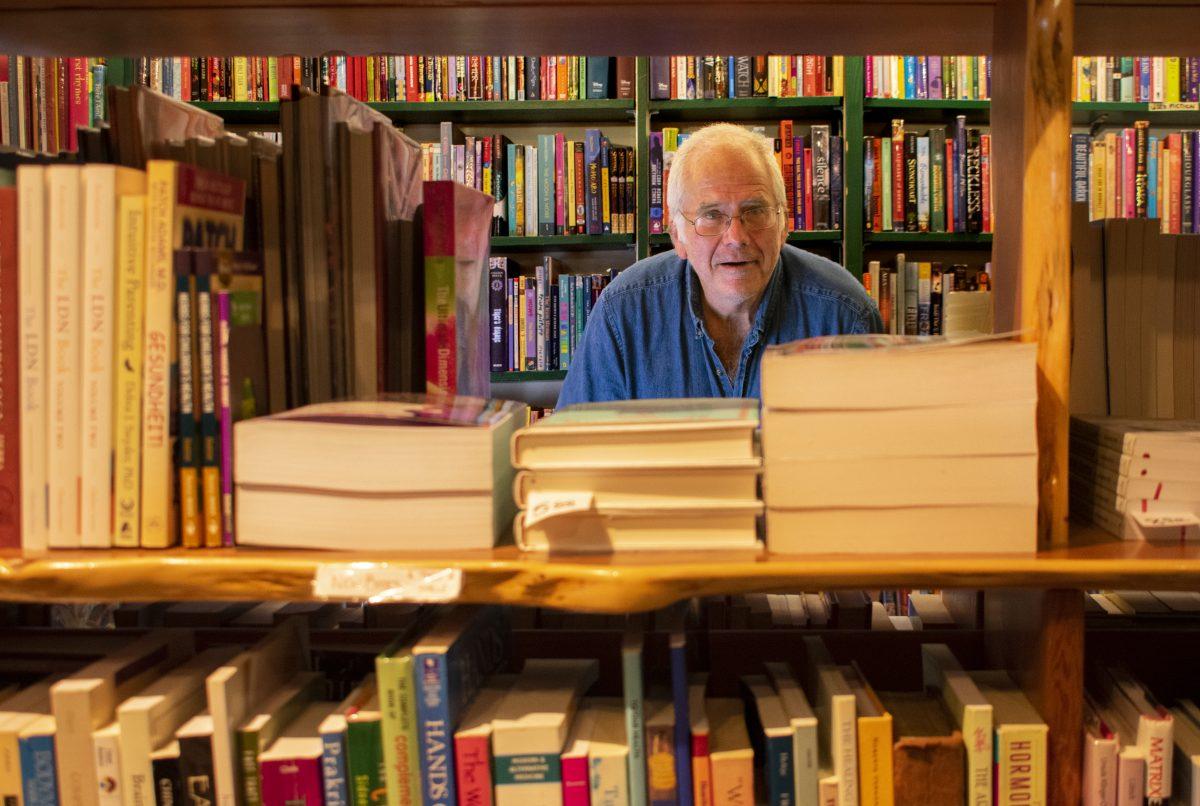

67-year-old Scott Landfield’s bookshop is well-loved. Shelves are piled high with classic and new novels, religious texts and historical books. Staff favorites are noted on handwritten cards littered throughout the bookstore. Even the walls themselves are filled with Eugene history: the entire store is built with second-hand wood, with timber from over 75 different Oregon schools. And some of the chairs in the back of the shop are from the original Autzen Stadium.

“We’ve never bought anything new,” Landfield says. He’s been the owner of Tsunami Books for the past 24 years. Landfield used to have a partner, but he left 12 years ago. Though Landfield is the only owner now, he stays involved in every aspect of the bookstore.

“I clean the bookstore first thing. I clean the toilets,” Landfield says. “I figured, you know, if a CEO isn’t cleaning their own building’s toilets, they should be fired.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic started in Oregon in March 2020, Landfield says he worked hard to keep business flowing. But it wasn’t paying off right away. The phone wasn’t ringing. The bookstore wasn’t making any money. For the first time in his career, Landfield says he hated his job. But he says he knew that keeping the business running would pay off eventually.

“We figured, well, it’s books,” he says. “We all go home and read books, all of us. And we believe in books. So, we will suffer because of books.”

Landfield says he was worried about keeping the store employees during quarantine because of the unemployment benefits that were being offered to those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. But most stuck around by choice, and eventually, the shop adapted to the restrictions. The team has since opened up an online store, and they have been shipping books globally.

Amazon has become a powerful company in book sales since the emergence of online retailers –– the company accounts for 70% of online book sales, according to a report from Authors Guild, a professional organization for writers. Earlier this year, Amazon reported reaching over $100 billion in sales during the first 2021 financial quarter.

But one of the most important parts of a brick-and mortar-shop like Tsunami, to Landfield, is the community. According to Landfield, people stepped up to help the business out when the shop was struggling the most during the pandemic.

“We have been an underdog forever,” he says. “We always saw ourselves as a community bookstore. When we needed money, the community stepped up. Little 7-year-old kids were giving us $10 bills.”

24-year-old Maggie Gebhardt went to Tsunami four years ago for a poetry reading. Since then, she’s been back twice. One of the things she likes about the business is that it feels comfortable and that the selection is hand-picked by staff. Shopping locally is a priority for Gebhart.

“It’s not corporate-feeling,” she says. “I just think it’s nice that the people who are here curate a lot of the selection.”

For the first time in 25 years, Landfield says the business can pay the rent every month without his help — there have been times when he’s loaned the shop money from own credit card. Looking forward, Landfield says he wants to retire in the next few years. But he will miss working at the bookstore.

“I got to see kids grow up and the kids continue to come through, you know,” he says. “Books are for the mind and for the heart, to touch things for our inner selves, our best selves.”

B&B Distributors:

B&B Distributors is a small shop nestled near a Taco Bell and a laundromat on West Sixth Avenue in Eugene. The outside of the building is grey with a bright-red sign reading “Adult Store” on the front. Inside, shelves are lined with hundreds of adult DVDs and sex toys.

23-year-old Kat Kay has been around the family business since it started in 1995. Once the pandemic hit Oregon and she graduated from the University of Oregon, Kay became more involved with the shop. She says her dad and uncle are nearing retirement, meaning that Kay and other family members will start taking over the business. Her job right now is manning the register, taking inventory and doing some of the branding work for B&B Distributors.

“I definitely enjoy that I get to help people learn more about themselves and their sexuality,” she says. “This is a place that can cater to anybody because everybody has sex.”

The store is focused on a brick-and-mortar kind of retail, rather than e-commerce, which has become less common since online retailers have grown in popularity. Adam and Eve, a primarily online adult store, has increased 30% in sales during the pandemic, according to a report from the New York Times. Meanwhile, IBISWorld reports that the brick-and-mortar adult store industry has declined 0.4 percent in profit from 2015. And websites like Pornhub that offer pornography online for free serve as strong competition to stores like B&B Distributors that sell DVD porn.

Kay says that because of the internet, the industry has changed quite a bit — people can have products delivered to them within just a few days. But there are some benefits to buying sex products in person.

“We get a lot more older males who aren’t as able to get their porn online,” Kay says. “It’s definitely catered to people who are not as inclined to use the internet.”

According to Pew Research Center, 25 percent of people 65 and older don’t use the internet. Kay says accessibility is important to B&B Distributors. In the future, Kay would like to grow B&B’s online presence to reach new audiences and people who wouldn’t otherwise come into a brick-and-mortar shop.

“You can have someone who is knowledgeable about the products that you’re face-to-face interacting with,” she says. “So if you have questions about which one’s best, you can get those recommendations right away.”

Kay remembers helping a customer find products during the beginning of the pandemic. A woman walked into the shop wearing gloves, a mask and a face shield. It was obvious to Kay that she cared about being safe.

“She told me that since the pandemic, she no longer felt safe hooking up with partners anymore since she needed to social distance,” Kay says. “As a result, she needed some toys for stimulation for the first time in her life.”

Kay was happy to make her pandemic situation more comfortable and to keep her safe and healthy. She was able to give suggestions, tips and tricks to get the customer products that were right for her — something websites like Pornhub or Adam and Eve could never offer.

House of Records:

House of Records lives in a sage-green house finished with a copper-red trim on 13th Avenue in Downtown Eugene. Inside on May 3rd, 55-year-old Greg Sutherland stood polishing a record with scraps from an old cotton T-shirt. He calls records artifacts and says polishing them is his favorite part of the job.

That morning, he finished sifting through 500 disks. It took him a few days to get through them all. He liked about 300 of them. For Sutherland, this is routine. “I’ve done the same thing every day for a decade,” Sutherland says.

Sutherland has been the manager of the House of Records for 35 years. He was a big fan of the store while he was in college at the University of Oregon. After three years of being a dedicated customer, the store hired him in 1986.

Records have been important to Sutherland for decades. And House of Records has a special charm that Sutherland can’t quite put his finger on. But it drew him in 38 years ago. He thinks it’s one of the best in the Pacific Northwest, right up there with popular shops in Portland and Seattle.

The House of Records has had some success in its sales since the pandemic hit Eugene. Sutherland says that a lot of that can be attributed to stay-at-home orders.

“People are getting to know their record collections more because of the pandemic,” he says. “They’re not going out and spending money at concerts.”

According to a report by Statistica, record sales have increased 30 fold from 2019 to 2021. The record player trend began a resurgence around 2010. Although vinyl sales have increased, so has the use of streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) released a report in 2018 saying that streaming services account for 75 percent of total music industry revenue. But an article from Engagdet speculates that the rise of vinyl sales can be partially attributed to streaming services –– streaming allows customers to explore music before purchasing a vinyl copy.

Sutherland says that a lot of recent customers have been younger college-age students. However, this isn’t new. When vinyl record sales took a massive hit during the late 90s and into the early 2000s, Sutherland says it was college kids who brought it all back.

“All the history of the entertainment industries, the movies, radio, television, it’s young people who get it moving,” Sutherland says. “They’re the ones who are paying attention and who care the most.”

Sutherland’s favorite part of working in a brick-and-mortar shop is the experience of holding and feeling the record itself.

“I don’t necessarily care as much as some people do about the atmosphere of record stores, but it’s important,” he says. “The tactile sensibility of feeling and holding the thing that you’re about to spend money on is still powerful.”

Barack Obama’s “The Audacity of Hope” and Oregon author Gary Snyder’s “No Nature” are just two of the many books on Landfield’s list of favorites. As the son of two bookstore owners and currently writing several books himself, Landfield has spent most of his life surrounded by literature. “Some of the books in here are older than me,” says Landfield with a grin. “Then again, I’m older than a lot of them too.”

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)