Story by Elisabeth Kramer

Photos by Branden Andersen

Quentin Holmes knows where he’s going. As president of the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery Association, Holmes is familiar with every gravestone on the cemetery’s 16 acres, an inner knowledge that guides his trek across the grounds (but never over the graves). Today he’s interested in one particular section, just left of the cemetery’s heart: the plot of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR).

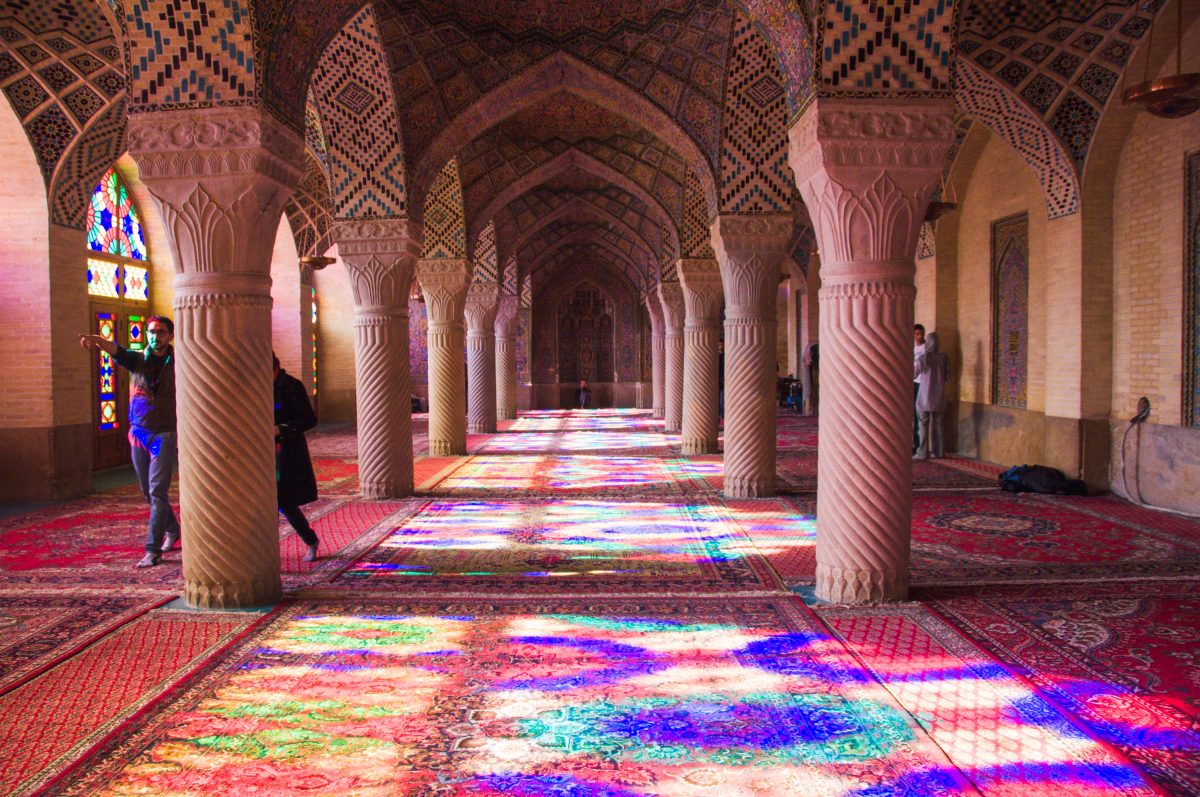

Here rows of markers surround a towering 25-foot, 8-ton statue commemorating a Union infantryman. After decades in the Oregon rain, the gravestones should appear more weathered but many gleam a brilliant white, new to the 139-year-old cemetery.

“Of the people who are here now, everybody has a stone,” Holmes says, gesturing toward the plot. “That would never have been done if it hadn’t been for the Sons of Union Veterans. We owe them a very great deal.”

Four years ago members of the Sons of Union Veterans—an organization, as the name suggests, composed of men descended from Yankee soldiers—approached Holmes about the cemetery’s unmarked graves. Many of them were in the GAR plot.

“The Sons of Union informed us that the men in the unmarked plots are entitled as veterans to have a military marker that the government will furnish,” Holmes says. “So they gathered the official proof that each man had served and sent that off to the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. In due time came back a stone for each man.”

Depending on the deceased’s military affiliation, the Sons of Union Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans cover the cost of mounting the marker and hosting a memorial ceremony. Every veteran receives such treatment in honor of the service they gave more than 150 years ago.

Above and Beyond

Perhaps the most notable Civil War veteran in the state, Louis Renninger is one of only four Congressional Medal of Honor recipients buried in Oregon. He’s also a reason why the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery has survived the growth of the University of Oregon.

“People ask ‘How come you’ve got 16 acres of cemetery in the middle of a busy city? Wouldn’t that be worth a lot of money?,’” Holmes says, “but because Renninger is buried here, this cemetery can never be moved.” The Union veteran’s unique award, which he received at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863, helped earn the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery its spot in the National Register of Historic Places, thus providing the degree of federal protection that keeps the cemetery in its current location.

“He has done above and beyond what anyone could be expected to do,” Holmes says. “He deserves to be at rest wherever he’s at. He cannot be disturbed.”

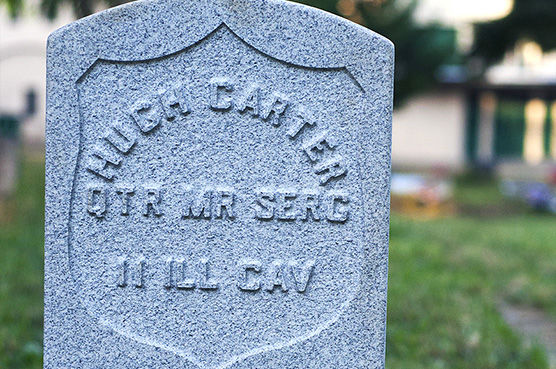

Renninger is one of more than 50 Civil War veterans buried in the cemetery. Although the majority of the graves have been recorded and marked during the past decade, new information continues to surface. Most recently, Sons of Union members Harold J. Slavik, Jr. and Randy Fletcher received a gravestone for Sergeant Hugh Carter. A Union veteran, Carter’s plot remained bare until handwritten records allowed Slavik and Fletcher to file for a marker, which was placed in July 2011.

“I don’t think anyone should be in an unmarked grave,” says Fletcher of the event’s significance. “At least we can do something about the military ones.”

Such is the thinking of Slavik, who has spearheaded the effort to locate Civil War graves in Oregon. Since becoming a Grave Registration Officer for the Sons of Union Veterans eight years ago, Slavik has walked almost every cemetery in the state. In all he’s identified more than 5,000 final resting places and expects to find at least that many more. It’s a mission that takes his own time and money, but one Slavik says is vital to honoring military service.

“We don’t want to lose these men,” he adds. “Whether the family wants to acknowledge that they served this country or not, as a veteran I want to.”

With a background in geology, Slavik uses United States Geological Survey quadrangle maps (each covers about 50 square miles) to locate the cemeteries in every Oregon county. He then systematically visits each spot to record the site’s graves.

“I walk up and down the rows looking at the dates of birth on the gravestones because a lot of Civil War veterans are buried under family or private gravestones,” Slavik says. “You wouldn’t otherwise know that they’re Civil War veterans.”

Once a grave of a potential veteran has been found, Slavik, like other Grave Registration Officers, uses online resources such as Ancestry.com and the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System to find enlistment, service, discharge, or pension records to verify the deceased’s military service. That information is what’s sent to Veterans Affairs, which then ships the marker to cemetery representatives like Holmes. For both Union and Confederate soldiers, the stone memorial stands above ground at about three feet. A slight point crowns the Confederate markers.

“As the story goes,” Slavik says, “the point is to keep the damn Yankees from sitting on the gravestone.”

A Memorial For Eternity

As the final step in the memorial process, mounting the marker allows those who did the research to celebrate yet another veteran remembered. Sons of Union Veterans or Sons of Confederate Veterans arrive at the ceremony in full Civil War regalia to honor the deceased’s service. The ceremony includes the firing of a three-volley musket salute.

“There’s nothing more awesome than going out and placing a headstone,” says Brent Jacobs, a Sons of Confederate Veterans member. “It’s a good service and people really appreciate what we’re doing.”

Although his involvement has not been as extensive as Slavik’s, Jacobs is Oregon’s other main contributor to the grave registration program. Currently Camp Commander for Colonel Isaac Williams Smith Camp #458 in Portland, Jacobs originally joined the Sons of Confederate Veterans in 1999 after discovering his ancestral connection to one Captain John Tyler Jacobs of Virginia.

“I told my grandpa about his own grandpa,” Jacobs says. “Captain Jacobs was captured in Montgomery County, Missouri, recruiting rebels. He fought over states’ rights, not slaves.”

In explaining this difference, Jacobs says he often encounters a “kneejerk reaction” against the Confederacy.

“People enjoy easy, short answers about the Civil War like that the North was good, the South bad; [Abraham] Lincoln good, [Robert E.] Lee bad,” he says. “I try not to get into long discussions about it all. If you want to hate black folks, go join the Ku Klux Klan. If you want to break away from the Union, go join the League of the South. [The Sons of Confederate Veterans] is not that organization.”

Unlike Jacobs, Slavik didn’t do the initial research that brought him to the Sons of Union. Instead, a friend of Slavik’s discovered through genealogical research that he has at least one Civil War veteran in the family.

“Turns out one of my great-great-grandfathers showed up in New York in October 1861 from Königsberg, Germany,” Slavik says. “He got off the boat and [US Army recruiters] said, ‘Hi. Glad you’re here. Sign this—you’re a citizen. Sign that—you’re in the army. Go over there and put the blue suit on.’”

Albert Janovski (also spelled Janowski) joined Company K of the 54th New York, an all-German speaking regiment. Units composed of men of the same ethnic background were not uncommon, Slavik says. In fact, when he established his own Sons of Union camp in 2007, Slavik named it after a member of an all German American regiment: Louis Renninger.

A Place to Rest

Back in the Eugene Pioneer Cemetery the statue of the Union infantryman casts a long shadow across the graves of his fellow veterans. Red, white, and blue flowers, mementos from Memorial Day, dot a few of the graves; the markers stand sparkling in the day’s dying sunshine.

“Everybody who is buried here has a stone,” Holmes says, “but not every stone has a person.” Turning to his right, he points to a grassy area not far from the memorial. “There’s one man who has a stone in the Civil War plot but his body is over here. He wanted to have a memorial next to his buddies.” Holmes turns back to look at the final resting spots of those men, many of whom once were anonymous beneath the ground.

“There’s something,” Holmes says, gazing at the infantryman, “about having gone to war together and having gone through more hell than you and I can ever imagine—there’s a kinship that gets developed that goes beyond our mortal means.”

Categories:

Immortal Markers

September 26, 2011

Immortal Markers

0

More to Discover