Story by Anais Keenon

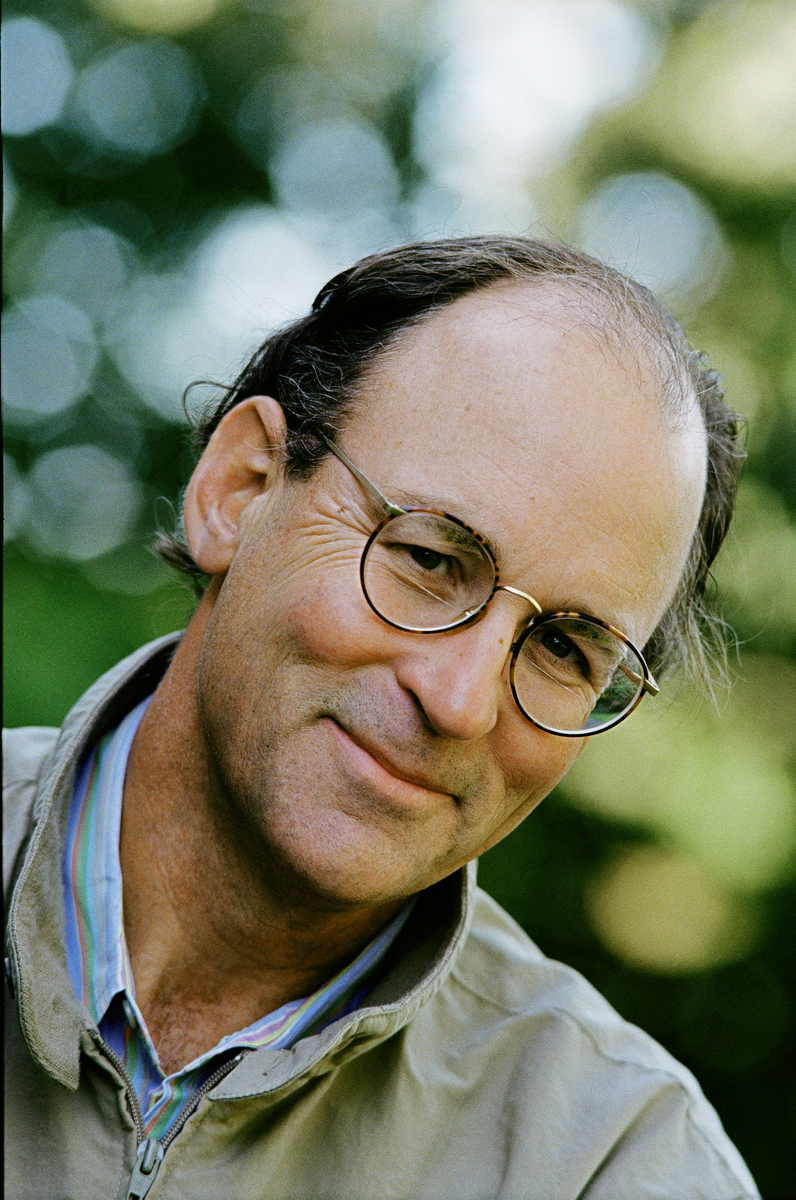

Photo provided by Tracy Kidder

It’s almost 9:00 am. Somewhere in Boston, a famous author is about to pick up the phone and call me. My head is a babbling stream of noise, and I’m increasingly worried about the fact that I can’t seem to form a coherent sentence. The phone rings, and then I hear Tracy Kidder speaking. Wow.

Kidder is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author whose most recent works include Strength in What Remains (2009), My Detachment (2005), and, perhaps most notably, Mountains Beyond Mountains (2003). This last novel—a biography of Dr. Paul Farmer, a humanitarian providing health care in Haiti—has appeared on many college reading lists throughout the United States, and was recently listed as the University of Oregon’s common reading for the 2010—2011 school year.

On Tuesday, March 1, Kidder will be giving a free public talk addressing some of the deeper messages behind Mountains Beyond Mountains and book signing at 7:00 p.m. in the Matthew Knight Arena. Before his speech, Ethos sat down with Kidder to discuss why he became a writer and the art of being a literary journalist.

Anais Keenon: You’ve been called a ‘literary journalist.’ Would you agree with that assessment?

Tracy Kidder: I think a lot of people who are interested in this genre have been arguing over what it should be called for quite a while. For a while it was called the ‘new journalism.’ That was a little inaccurate since it wasn’t new, really. Then they came up with this term ‘literary journalism.’ The problem with that is that it is a bit presumptuous. To call something ‘literary’ in general is to praise it. I don’t know that it is possible to determine what should be called literature until fifty years after the fact, or maybe even longer.

Others have thought of the term fiction, which I have obvious problems with. Changing facts and inventing composite characters is a problem. I don’t mind being called a writer, a journalist, or a literary journalist. I don’t think it matters. I like that the term literary journalist suggests that there is more to it than just collecting a bunch of facts and boldly presenting them.

AK: So as a literary journalist, how do you remain true to the person you are writing about and yet still maintain your voice as a storyteller?

TK: I don’t think there is a contradiction. In fact, sometimes the facts are inconvenient or seem inconvenient. Sometimes I have been writing and not looking back at my notes, and described things in a way that didn’t happen. Then I went back to my notes and saw the error. Usually, the way it actually happened is more interesting. It seems to me to be more interesting. I think trying to render human beings on the page is very difficult.

As for objectivity, if I understand the term, it is worth pursuing. I think it is worth pursuing if it means getting the facts right and looking at your own work with the kind of affection a mother might feel for a child. I don’t think that is the issue: objectivity. I think in general what the real pest is when you are writing about public figures, so it is different. If you are writing about individuals, I think the main task is to try to understand what you have seen and to make that believable to the reader, but also to try to express your justified belief of a version of events. It is perfectly possible to write a very factual account of something. This is a really complicated subject.

AK: In writing your books, what response do you hope to evoke from the public?

TK: I don’t calculate that. I don’t write to do a good deed. That is not my aim. If it had been, not that many people would have wanted to read either book. What I hope for is what I propose every writer hopes for, which is to provide a kind of transportation. If I am a storyteller, then of course my overwhelming interest is in trying to render human character. What you hope for is to get into the reader’s imagination when you find yourself speaking to the characters.

You find yourself saying, ‘Don’t do that!’ Or you think ‘that could be me.’ I look for some form of transportation in stories. If you are interested in people, the people you are writing about, you of course get interested in what preoccupies them. With Paul Farmer, I became interested in AIDS and mal-distribution of public health. I became interested in genocide and the importance of public health in a shattered nation. I don’t write theoretically or didactically.

I have one primary reader, my editor and a few secondary ones. All of them are very valuable to me. I suppose I have them in mind when I write but it is hard to imagine an audience much bigger than specific people. If you were writing for a specific audience you would have to face the fact that you can’t write for everybody.

I think of the life of the great English romantic poet John Keats. In one of his letters he said something about the holiness of the heart’s affection. There has to be some merit in the subject matter of a writer. The writer has to feel it somehow opening up. They have to feel the important gravitational force. I don’t write for an audience but I do have a reader in mind. Not a particular person, but I think one should be polite to one’s reader. Otherwise writing becomes a kind of showing off, and that is no good.

AK: Looking at the body of your work, there seems to be a transition from more localized American themes to an international focus on people in places like Haiti and Burundi. What brought about that change?

TK: I’m not sure! That’s true and yet the actual sequence of things was that I have found myself as I often do, even right now, wondering what to do next. Around 1994 I heard about something interesting that was happening in Haiti, where I had never been. We had sent a huge number of troops there to restore the constitutionally elected government. It sounded like American troops were doing interesting work because they weren’t there to kill people. Having been a soldier myself, I thought that would be interesting. It would get me out of my office. That is when I met Paul Farmer. When I came home I found myself writing another book about something close to home. Once I had finished that, again somewhat at a loss for what to do next, I thought I should see Paul Farmer again. It took me a while to move away from home.

AK: So it wasn’t a conscious decision?

TK: The fact is that I have always changed the subject, generally. I have always changed the main subject like in Mountains Beyond Mountains. I managed to change the subject from one book to the other. I like to say that it is one of the great things about my job! I get to change the subject every four years without changing jobs. The setting hadn’t changed much in quite some time. It seems ironic to me because I now find myself a little too old and fussy to travel easily. Anyway, I am determined to write something in the United States next.

AK: Of all the possible careers in the world, what drew you to writing?

TK: I have an uncle who took out a subscription to The Wall Street Journal. This was a message from him that I was a privileged boy and all of these opportunities could earn me a living. I was stubborn. I had conceived this ambition in college when I took a course from a great translator and poet Robert Fitzgerald. He made me feel that writing can be a high calling and that it might be available to me.

Remember, it was the 1960s and writing was still rather romantic. I also thought it was a good way to meet and impress girls. This was how I came to identify myself as a writer. Before I had anything published, I thought of myself as a writer. Somewhere along the line, you keep coming to forks in the road and you keep taking one fork and another. After a while you could never figure out how to get back to where you were. These things have a momentum of their own and I don’t regret any of it. I have had a great deal of luck. I think anyone who writes for a living and doesn’t admit to be extremely lucky is nuts!

Categories:

Tracy Kidder, Telling His Own Story

February 28, 2011

Tracy Kidder, Telling His Own Story

0