Story by Keegan Clements-Housser

Photo provided by Finding Face

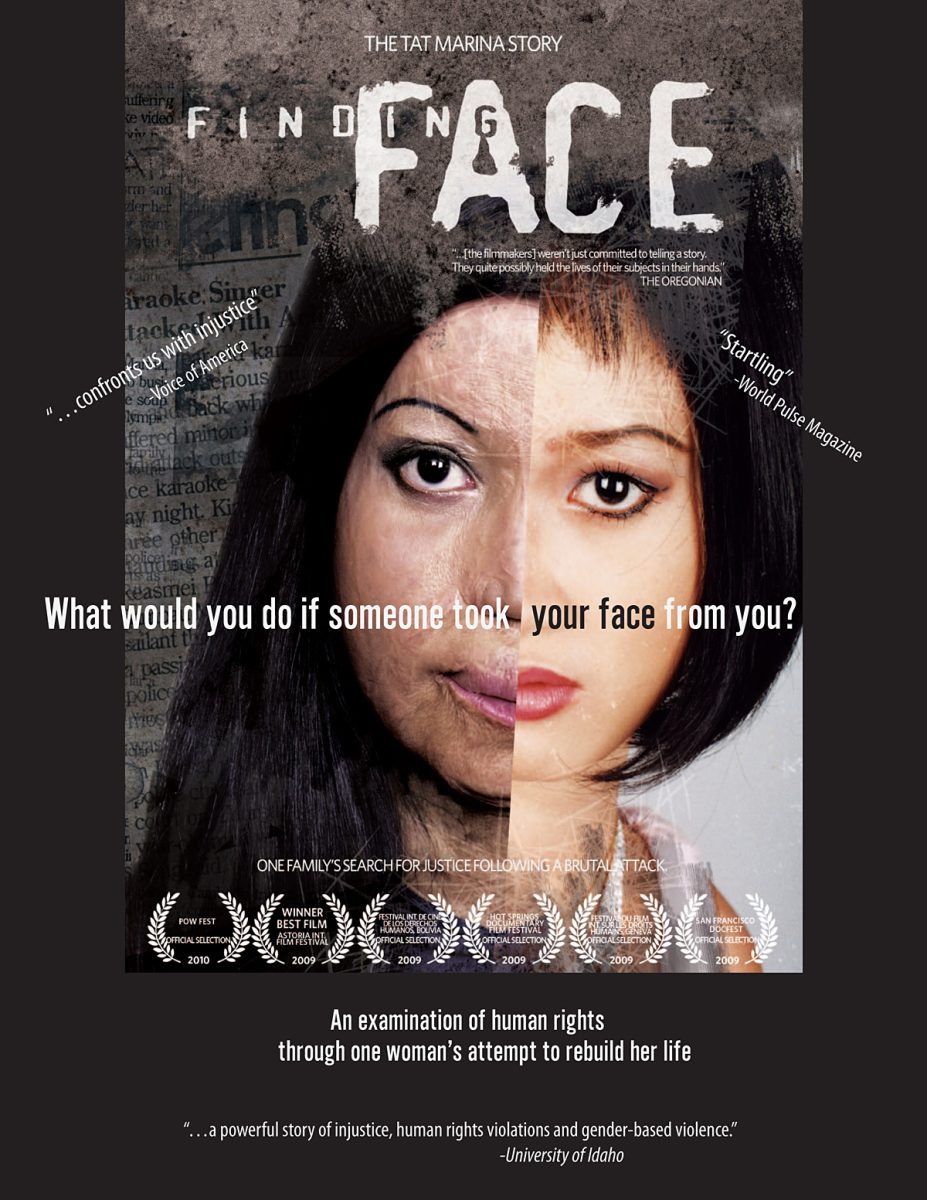

Today, Tat Marina is horribly scarred.

Even after a series of over twenty plastic surgery procedures to repair the damage that was done to her face and forty-five percent of her body when she was beaten into unconsciousness and coated with nitric acid, Marina remains almost unrecognizable. She’s certainly not recognizable as the music video starlet she once was before she fell victim to the rising trend of domestic acid attacks.

This isn’t the first time Marina’s story has been heard in Eugene—last March, the University of Oregon’s Women of Color Project showed a screening of the documentary Finding Face, which features Marina as part of an attempt to raise awareness of global domestic attacks against women.

Yet a little more than a year later, no one involved in the project remains on campus, and her story—outside of a few select people in the Women’s and Gender Studies department—remains largely unknown. The story was even revisited this January, when the documentary aired once more on local channels KEPB and KOAC.

Admittedly—or perhaps tellingly—it was aired at the less-than-prime time of 4 a.m. with many involved in the original airing, including in Women’s and Gender Studies, unaware of its return.

Marina, like many acid victims across the world, was attacked in an act of jealousy. The at first unwitting and then unwilling mistress of a prominent Cambodian politician, Marina ran afoul of the man’s wife, who decided to do something worse than kill her competition; she decided to force Marina to live in a horribly disfigured body for the rest of her days. Also like many others, Marina’s attacker was never sentenced for any crime or even questioned, despite being well-known and clearly linked to the attack.

Such attacks—and the lack of justice thereafter—are hardly uncommon, especially in developing nations, even though comprehensive statistics on the attacks are hard to come by. For example, according to the Bangladesh-based Acid Survivors Foundation (ASF), one of the organizations that does track acid violence, in 2010 there were 153 reported attacks in Bangladesh alone, with more believed to be unreported. Out of all of these attacks, only seven individuals were convicted in connection to the crimes.

However, these attacks aren’t limited to developing nations. In 2006, twenty-eight-year-old Karli Butler, a resident of Chicago, was attacked with car battery acid not because of anything she did, but in retaliation to the actions of her then-boyfriend.

“He was allegedly doing some bad things on the street to people, like robbing them,” she says. “Instead of them retaliating against him, they retaliated against me.”

The acid coated thirty percent of Butler’s body. In the aftermath of the attack, she was left running down the street naked in search of help, having desperately pulled off all of her melting clothes.

Despite the brutality and commonality of these attacks—indeed, in 2010 Chicago was the scene of an additional four domestic acid attacks on women—they remain relatively obscure.

According to Emily Hutto, online advocate for the makers and subjects of Finding Face, the reason behind the obscurity is simply how media covering this topic is handled.

“There are a lot of big-time organizations that are reporting on and doing things to combat acid violence, such as Cornell Law School and other groups in collaboration with them,” she says. “[But] you have to go through an institution to even hear about it.”

The biggest problem, Hutto says, is the lack of a trickle-down effect when it came to media about the issue. Although she conceded that large groups like the United Nations Women and Population Foundation do put lots of effort into tracking and preventing acid violence, Hutto explains that nobody hears about their efforts or the case itself because the right media support doesn’t exist yet, and the organizations themselves aren’t communicative enough. Or, as she puts it: “When was the last time you got someone from the UN on the phone?”

However, there are more approachable organizations dedicated to assisting survivors of acid violence, as well as making sure organizations like the UN are aware of acid attacks and their victims. One such organization is the United Kingdom-based Acid Survivor Trust International (ASTI).

With partner organizations in Pakistan, Cambodia, Uganda, Nepal, and Bangladesh, ASTI focuses on getting much-needed medical help, legal support, and general aid to acid attack survivors, according to Programmes Director Kate Bagley.

“After we’re done helping them with the medical part of their treatment, we help them get job skills,” she explains. “Or [we] get them integrated back into their villages and their families, give them psycho-social therapy, that sort of thing.”

When asked what the average person, regardless of their location in the world, could do to help acid violence, Bagley’s answer was straight-forward: donate to ASTI and other groups like it whenever possible, keep yourself informed, and, most of all, spread awareness about the issue.

“Study up on it,” she says. “Do papers on it. Do research on it. Write your thesis on it. That would be great. What we need most is more people looking into it and being aware of it.”

Finding Face will be screening during the DisOrient Film Festival at 12:15 p.m. on Saturday, April 30, at the Bijou Arts Cinemas.

Categories:

Acid Attacks Continue, Documentary Returns

April 18, 2011

Acid Attacks Continue, Documentary Returns

0