Dale Enzenbacher lives in a storage unit converted into an apartment. Within a complex of tan and green storage spaces, Enzenbacher’s stands alone. His front door is layered with a colorful collection of art and miscellaneous decorations around a sign stating, “The Creator Is Hidden in His Workshop.” Inside, his intricate fantasy and science fiction drawings cover the walls while trinkets and sculptures occupy nearly every surface. His mattress leans against the wall to create space for what becomes his art studio during the day.

In a way, the clutter creates comfort. With the local radio on in the background, Enzenbacher sits down to focus on his art as he has done every day in this space for more than three years.

“It’s where I feel peaceful doing my work. It has become very automatic, and after I work a while it’s just like meditating,” Enzenbacher says.

He is part of the historically offbeat community of artists in Eugene’s Whiteaker neighborhood, many of whom are also struggling to maintain their footing as the neighborhood experiences a transition. What was first an anarchist, artistic, and activist hub is now one of the city’s top destinations for entertainment and nightlife.

In 2007, Ninkasi Brewing Company moved into the Whiteaker and has since made four expansions including larger production facilities, offices, a tasting room, and a local distribution space. In the wake of Ninkasi’s success, other microbreweries, distilleries, wine bars, and restaurants have entered the scene. The changing demographics of businesses and patrons mark a transformation that is pricing out longtime Whiteaker residents and compromising the whimsical flavor of the community as the area slowly becomes Eugene’s “Brewery District”.

“It’s sort of like a tourist attraction, it’s a circus show to them, taking pictures and pointing,” says Brian Schaffer, a Whiteaker resident for more than ten years. Schaffer previously lived across the street from Ninkasi in a building that is now a chic farm-to-table restaurant. “You see more places opening who are catering to people who they want to bring into the neighborhood, people who don’t actually live here,” he says.

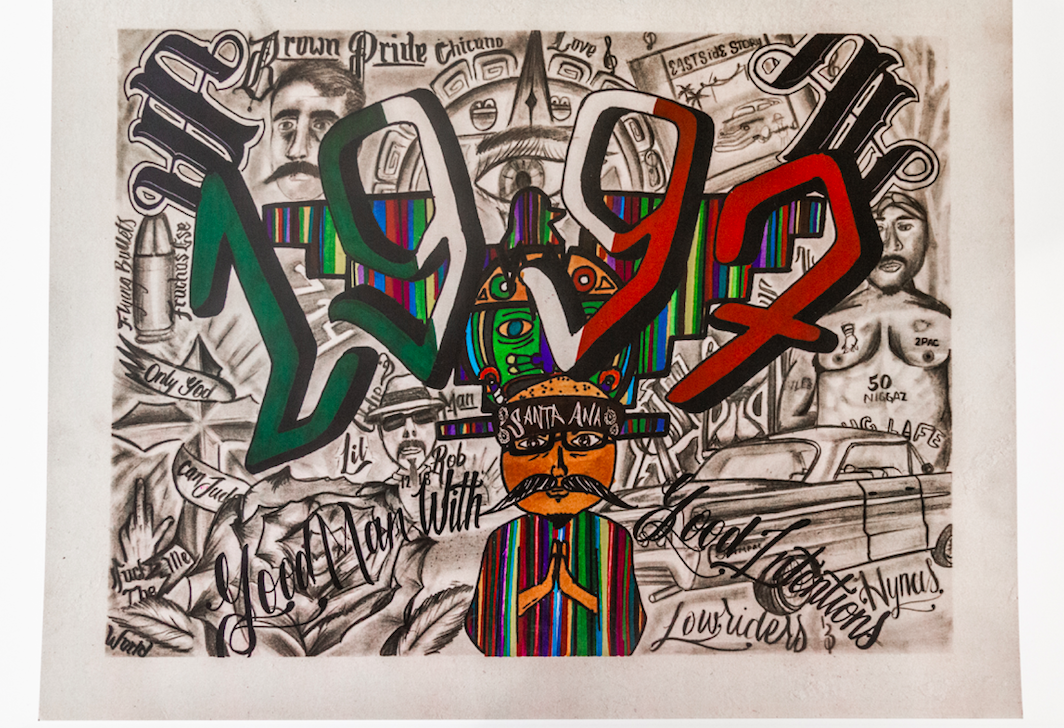

Many of the artists experiencing the effects of accelerated changes in the Whiteaker possess an eccentric skill set, working within the category of Outsider Art. This style emerges when artists lack formal training and therefore reject traditional creative methods. Outsider artists create “raw art,” which has not yet been molded by instruction or cultural norms and often comes in the form of surrealist fantasy interpretations of the world.

The genre came out of a realization in the early 19th century that psychiatric patients’ authentic content, independent from the art scene of the time, was a form of art in itself. Jean Dubuffet, a French painter and sculptor who helped lead the movement then called art brut (the term Outsider Art wasn’t coined until 1972 by art critic Roger Cardinal), believed this kind of expression was a more organic method of creation requiring raw skill. The result is highly imaginative art that, even in a world of advanced special effects, would be difficult to replicate.

The Whiteaker is a local hub for this contemporary style of expression and is struggling to maintain this iconic creative culture. In an effort to preserve it, artists are converging to help one another stay afloat through neighborhood organizations like the Whiteaker Independent Visual Arts Council (WIVAC). WIVAC’s primary focus is on assisting artists in the promotion and sale of their artwork.

“We hope the artists will be able to generate enough extra income to be able to stay housed in the neighborhood in the face of impending changes,” Haint Bradley, a Whiteaker artist and creator of the WIVAC, says. Many members of the group have fluctuating incomes, unstable housing arrangements, and lack access to fundamental promotional resources, such as the Internet.

“The whole gist of the idea is to use the uniqueness of the art, the high concentration of visual artists, and the free spirited culture of the neighborhood to save its own self from gentrification,” Bradley says. But this is only the first step in a long process with the goal of developing the Whiteaker as a national destination for art. “I don’t want to make any money on anyone,” Bradley says. “I am just doing it for the sake of the art and the artists. That’s my payoff.” This dedication and diligence has come to define Eugene’s Outsider artists, who paint, draw, sculpt, and chisel because of a love for it rather than satisfying any extrinsic motivation.

Ron LaFond, a Whiteaker resident and artist since 1980, has been involved with Bradley in the organization and promotion of the WIVAC. LaFond contributes to the neighborhood’s Outsider Art scene through his surrealist paintings and computer-generated artwork. For him, the recent development of the neighborhood reflects a pattern of art’s ability to attract newcomers.

“This is going to happen to any town, and it usually happens where the artists live because the artists are the ones giving it character,” he says.

Sam Gorrin is a local artist who has felt the positive impact of Bradley’s initiatives. When Bradley saw Gorrin and his work spread out on the ground in a local park, he was blown away. The WIVAC was able to locate a living arrangement with low rent where Gorrin can live and produce his artwork, a significant transition for someone who for years has bounced from place to place, unable to find stability.

Inside the apartment found for Gorrin, a single set of floodlights reveal his detailed pen and ink drawings covering the walls. Boxes of his minimal belongings hug the corners around his makeshift mattress and art supplies; everything he owns is within this space, which is the best he can afford and the nicest place he has ever had.

“There hasn’t been a single thing in my life that has been constant other than my art,” he says. “If I was going to have to be homeless in the back of my car and that’s what it took to sit there and draw, then fine.”

Crouching down to twist metal for his jewelry projects, there is a sense of accomplishment written on Gorrin’s face. After years wandering, couch surfing, and living out of his car, he is now in a place where he can store and sell his work and sleep comfortably. Although his prices are low, Gorrin has even saved enough money for a drafting table which will be his first formal work station.

“I spent a really long time feeling like there wasn’t anything I had to show for all my time here. Art reminds me that I’m here and that I actually did something with my time.”

His progress and recent success is an unusual story in a pool of unfortunate instances in which artists aren’t able to establish themselves. They have to choose between living on the streets and moving out of the neighborhood to nearby areas such as Bethel or Trainsong. While the WIVAC works to avoid this, the forces of gentrification and the Whiteaker’s growing reputation as a pub paradise are proving difficult to work against.

The Whiteaker is a small-scale example of gentrification happening in cities across the country where original culture is compromised and a new “character” takes hold. Businesses are drawn to areas with color and potential where they can feed off the energy in the community.

Nicole Nelson is Ninkasi Brewing Company’s director of the “Beer is Love” program, which focuses on community outreach and support. Beer is Love involves donations, sponsorship of events, and participation in community activities. Nelson has worked for Ninkasi for five years and has experienced the challenges associated with integration into a neighborhood.

“We are in a mixed industry and residential zone so sometimes you are stepping on peoples toes,” Nelson says. “We have done big expansions in a neighborhood that values small business. All of a sudden, we’re a really big business and there are some growing pains that go along with that.”

While a substantial percentage of Ninkasi’s 100 employees do live in the Whiteaker, the large walls and growing national fan base of the company’s beer naturally create tension between the business and longtime residents who feel the company has changed.

“We still view ourselves as the village brewer and Ninkasi became what it is because the village supported us. That’s a hard part of development. As you expand and grow and more people try your product, sometimes it looks like you don’t hold the same values, but we do,” Nelson says.

In a neighborhood where change seems inevitable, maintaining values and exercising them at an even deeper level could be imperative. The preservation of the Whiteaker’s colorful personality begins with addressing lesser-known artists and struggling members of the community.

“It has got to be a mutual respect between the breweries and the artists, who were here first,” Enzenbacher says, who lives next door to Ninkasi’s brewery. “We can’t be scared of the word gentrification,” he adds, stating that we must address what this word means for the businesses and artists of the Whiteaker. Enzenbacher maintains a positive outlook on local support for artists, hoping the increasing volume of people entering the neighborhood to sample beer will result in more sales of local art.

Although the Brewery District is strong and growing every day as trendy pubs crop up across the Whiteaker, the artists are becoming stronger as well. If any sort of cultural partnership between artist and business is going to take place, the clock is ticking and the artists are waiting. For now, the artists will keep creating and support will keep coming from organizations like WIVAC.

“I’m never going to give up,” Enzenbacher says. “If you’re an artist, you have to stick with it and keep coming up with ideas. If something doesn’t work, just bend it and pursue the idea in a different way. You have to keep running up against the wall and eventually the wall will give way,” he says.

Categories:

The heART of the Whiteaker

February 3, 2015

DMERYL PHOTOGRAPHY

Artists in the historic Whiteaker neighborhood struggle to preserve its unique character.

0

More to Discover