I wake up to the sound of my alarm blaring from my phone. I groggily turn it off and check the time: 6:30 a.m. My writing class starts at 8 a.m., and I need to get ready. As I sit up, I begin to feel a pulsating pain rush through the right side of my head. I squeeze my eyes shut as I clutch my head in my hands, and lay back down. I can’t afford to miss class again, but I can’t physically move. I feel as though I’m going to throw up from the pain. It’s a pain that I’m all too familiar with: a migraine.

My boyfriend wakes up next, and sees the pain that I’m in. I give him a head nod, signaling that I can’t go to class again. He gets up out of bed quietly, leaving the lights off, and shortly returns with an ice pack. I place it on my forehead. I’m not supposed to take my prescription during the day, but I do it anyway. I wish Tylenol or ibuprofen worked, but I have nothing else to help take the edge off. I close my eyes, waiting for sleep to take the pain away, knowing that I’m bedridden the rest of the day.

For the past six years, I’ve woken up not knowing how my day will be. Whether it will be a normal day or one filled with pain, the daily uncertainty is not new to me. I’ve been living with chronic migraines since I was 13 years old due to a concussion. This “mild” concussion happened when my brother accidentally dropped me on my head as we were wrestling outside. After it had happened I lost my vision for six months, and doctors could not figure out why.

After multiple MRI scans my neurologist discovered that I was born with Chiari Malformation, a growth where the brain tissue extends into the spinal cord. The growth intensified my concussion symptoms, and that was why I was left temporarily blind. After the concussion symptoms subsided and my vision came back, I noticed that my head was constantly hurting. That’s when I was diagnosed with chronic migraines and Chiari Malformation.

Migraines are recurrent, throbbing headaches that typically affect one side of the head and are often accompanied by nausea and disturbed vision. In order to be diagnosed with chronic migraines you need to be getting them at least 15 times a month. For the past six years I have met these standards, getting migraines sometimes more often than that. As a college student trying to balance classes, work, social life and relationships, I have to remember that I’m spending most of my month in agonizing pain.

The first way I can tell that I’m about to have a migraine is when my environment is no longer controlled. This can happen if I’m in a very noisy area, the lights are fluorescent or the smells are too intense. The scent-filled store Bath & Body Works is a great example; I have never been able to go near that store for more than 10 seconds without it triggering a migraine. If I’m shopping with friends or on a break from my retail job I avoid that store as if my life depends on it.

Because of chronic migraines, I’ve had to avoid a lot of places, but I’ve learned how to make my own accommodations. Sunglasses and earplugs with noise reduction headphones over them are my go-to for concerts. I can still hear, see and feel the music without feeling like my head is getting nailed by a jackhammer. When I go to bed, I wear an eye mask that doubles as an ice pack to help release any tension before I sleep and hopefully prevent waking up with a migraine. But no matter how hard I try to avoid them, migraines are sometimes inevitable. One day I’m in bed trying to sleep it off, and the next I’m trying to pay attention in class while attempting to avoid the bright fluorescent lights.

Kendall Culley is a sophomore at Southern Oregon University who started getting migraines earlier this year. She does not know yet what the underlying cause of her chronic pain is, but still maintains a positive attitude about it.

“Some days aren’t the best and then having a migraine doesn’t make it better, but most of the time I can stay happy and positive, which also helps distract me from it and makes it a bit better,” she says. “It’s the best I can do sometimes, is to just push on and look at the positive, even though I’m not feeling that great.”

While attending college and having a part-time job, Culley says she wishes the people in her life could understand how chronic migraines have affected her. There are days when you can’t do it all at once, but that doesn’t mean you can never do it all.

“I have had many people discredit my migraines, and it’s hard to explain because some people don’t understand how bad it hurts but that I’m still there pushing through the pain,” she says.

A normal day in my life with chronic migraine is unpredictable. Although I am a full-time college student and have a part-time job, I still have to acknowledge that sometimes I can’t do both. There are days when I can’t go to class and days when I have to call out of work.

According to the American Migraine Foundation, migraines might be linked to genetics, and one in five women suffer migraines, compared to one in 16 for men. Chronic migraines can also be caused by other factors, such as concussions, car accidents or a medical condition. One out of 11 adolescents get chronic migraines, but are often left undiagnosed.

It’s difficult to know why migraines, especially in adolescents, are overlooked. Also according to the American Migraine Foundation, “Migraines in children and teens often goes untreated because, unlike adults, children have a more difficult time understanding the pain and disruption caused by their migraine.”

Adolescents’ pain might also be overlooked because doctors and school officials see it as just a headache, or as an excuse to get out of school for a day. Last year I was referred to a doctor who was a migraine specialist. She said that the pain was all in my head and that my neurologist was purposely giving me the wrong dosage of medication. I never went back to that doctor again.

Author and activist Charlotte Laws, who has had chronic migraines since she was a toddler, says doctors and practitioners often don’t acknowledge migraines as they should. In her case, this could have been because she was only a child or because they misunderstood her pain. Doctors will often downplay a migraine, making the sufferer feel as though their migraine is not as bad as it truly is.

“The migraine sufferer usually knows way more than his or her doctor about migraines,” Laws says. “I always have to teach my doctor about a migraine as he or she desperately flips through medical books trying to keep up with me.”

Despite suffering from migraines from a young age, Laws says she was only diagnosed when she was18 years old. She called her childhood migraines “eye aches” because she did not know what migraines were.

“My adoptive parents called me a hypochondriac throughout my childhood because they thought I was exaggerating or inventing the pain. The migraine episodes lasted for three days nonstop during childhood,” she says.

Her pain was so great that she occasionally considered taking her own life. “After days and days of nonstop pain, sometimes I thought about suicide. I remember this happening as an adolescent and teen,” she says. “I would get desperate to stop the pain. There were times that I actually beat my head or banged it against a wall — this did not make me feel better, by the way. I don’t have these suicidal thoughts anymore.”

There is no cure for chronic migraines. There are many different medications out there that I have tried: Maxalt, Imitrex, Sumatriptan Injections, Topamax. But my body eventually gets used to certain medications, and they no longer work. Maybe someday scientists will create a medication that completely alleviate my migraines. Maybe they will release a special tool that will predict migraines for me days in advance.

But Laws doesn’t see that happening soon, because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sometimes makes decisions for those who suffer from chronic pain.

“I used to take the medicine Cafergot PB which worked really well for me, but at some point the FDA decided it was ‘not necessary,’” she recalls. Not only does the FDA do this, but so do insurance companies. Insurance companies have a habit of denying coverage of necessary medications that migraine sufferers need. I’ve encountered this problem with my own insurance company; they denied certain medications simply because they felt as though I didn’t need it.

It’s no secret that migraines can affect someone’s career, relationships and social life. I feel like my pain is treated as an inconvenience for everyone except me, and I’m glad I’m not the only one this happens to. Laws mentions that one of the ways migraines have affected her social life is when she was pregnant with her daughter, as the medicine’s possible side effects could harm the baby.

“It was nine months of a total nightmare,” she says.

Migraine sufferers have to deal with the stigma that migraines are over exaggerated headaches, and that our chronic pain is invalid. Sometimes we don’t feel heard or accepted because of it, and that can make life very difficult. Just because you can’t see that I’m having a migraine doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

My migraine episodes tend to last anywhere from six hours to two full days. When this happens all I can do is sleep, minimize my screen time and use any resources to make the pain minimal. It feels as though I have to put my life on pause whenever I get a migraine, and there isn’t anything I can do to change that. As I lay in bed waiting for the throbbing in my brain to end, I remember that I am not the only person suffering from this disabling pain. I hope that someday those who don’t suffer from chronic migraines understand that migraines are more than just a headache.

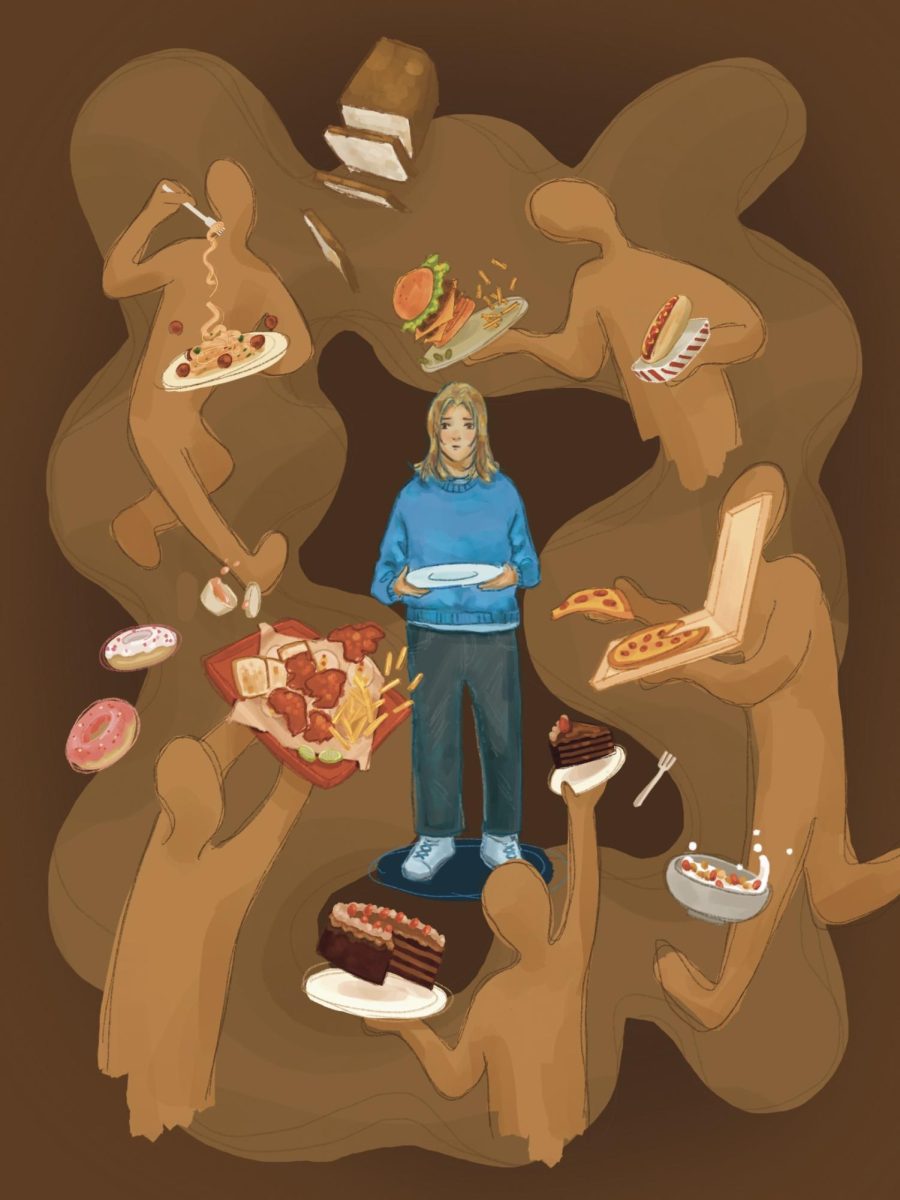

Art by Eleanor Klock

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)