Mahfoudha al-Balushi knew about Middle Eastern stereotypes, but she wasn’t sure what questions to expect from people when she came to the University of Oregon from her home country in Oman.

So when a stranger approached al-Balushi on the street and asked how her camels were, she didn’t quite know how to respond.

“She thought that I had camels. Imagine. I had no answer for her,” al-Balushi says. “Maybe she was a kind lady, I don’t know what she meant exactly, or maybe she decided from the media that all people from the Middle East are riding camels.”

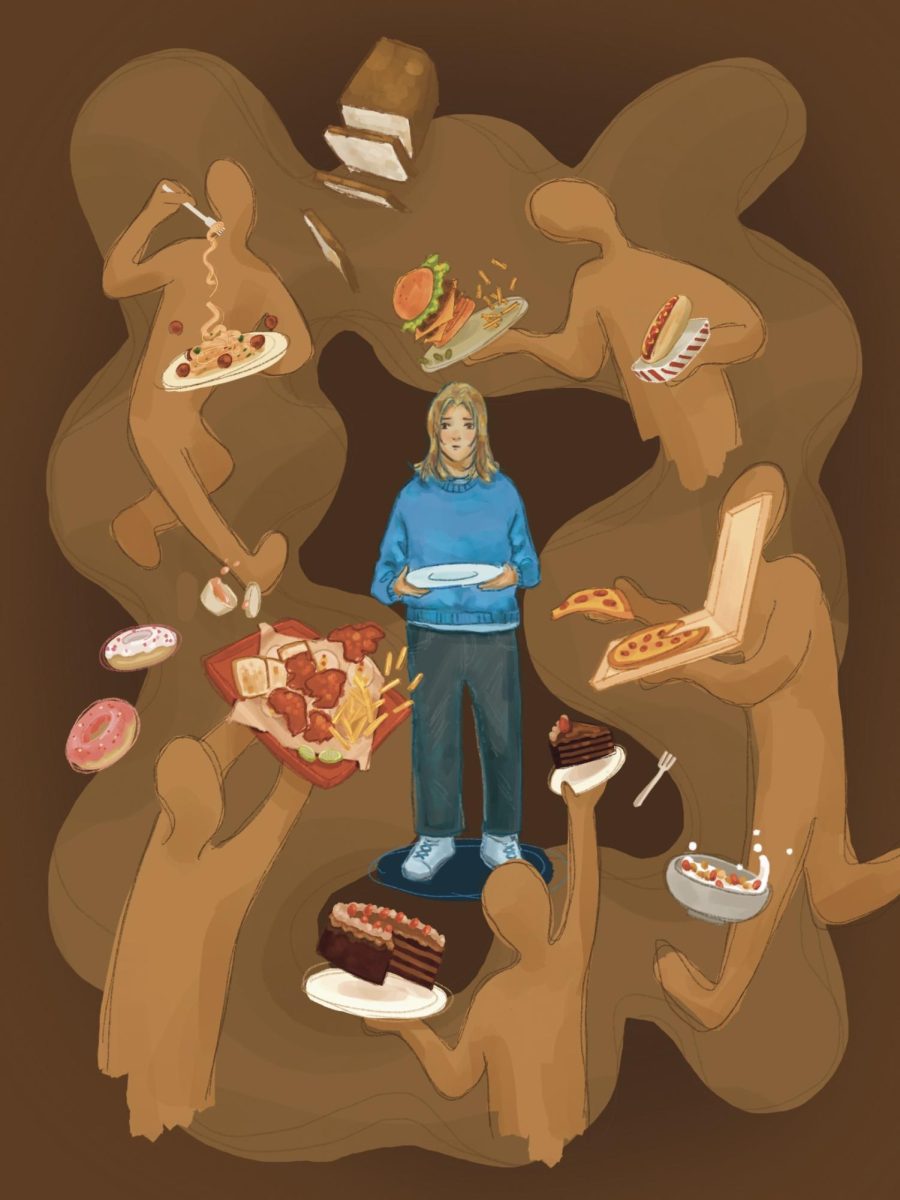

For some people who have never traveled to the Middle East, when they hear about the region they think about what they’ve seen in the media.They imagine sprawling deserts filled with roaming camels or their minds jump to more grim ideas about ISIS and war.

When it comes to the perceived ideas that all Middle Eastern countries are plagued by conflict, the reaction is arguably warranted. News coverage of the Middle East widely fixates on violence. Browse the stories in any major news outlet that has a “Middle East” section like The New York Times and there’s no shortage of headlines such as “Saudi-Led Airstrikes in Yemen Kill More Than 60 in Prison, Rebels say” or “Suicide Bombers Hit Hamas Police Checkpoints in Gaza.” Body counts and bombs are a staple of Middle East news sections.

The news can be a helpful, easily accessible source of information to better understand a region and its complexities, but issues start to arise when the news is the sole source of information someone has on a region and its people. Stereotypes start to take shape that may be accurate in some cases but widely fail to reflect reality.

Novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns of this problem in her “The danger of a single story” TED speech.

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story,” she says.

This issue of the single story has a tendency to plague countries within the Middle East. Oman – a quiet, peaceful country located in the Arabian Gulf – is no exception.

Mohamed al-Bulushi, Mahfoudha al-Balushi’s brother who lived in Louisiana for five years while studying for his bachelor’s degree, had many American friends and classmates who believed in a single story about the Middle East.

“When they asked me where I was from and I said I’m from Oman, first of all, they don’t know Oman. They don’t know if it’s a country, a name or something like that,” he says. “When I told them Oman is near Dubai or Saudi Arabia, or that Oman is in the Middle East, they think that, like, ISIS is over there.”

Mohamed al-Bulushi was disheartened when he heard this initial belief in the single story, but he says that once he explained Oman is perfectly safe – and ISIS-free – his friends in Louisiana were quick to understand the reality of the situation.

“I kept telling them the truth and the facts about what’s happening. That these wars are happening in other parts of the Middle East,” he says. “And it’s not the Middle East actually, it’s just in Syria and a couple of other countries.”

Mahfoudha al-Balushi says the single story, reinforced by the media, is precisely to blame for spreading these stereotypes of the Middle East, but the people who believe it are not necessarily at fault.

“In one way, you cannot blame them because media is the only source they have. They cannot travel, they cannot see the world, so how would they know what is happening there?” she says.

Chloe Simmons, a master’s student at the UO who spent eight weeks studying abroad in Amman, Jordan, says she had friends and family who knew little to nothing about the Middle East beyond what they heard from the news.

“A lot of my friends and family just think of the Middle East as like a blanket statement of a country and they don’t know specific countries within it except for the big ones we hear about in the news like Syria or Yemen,” Simmons says.

When Simmons finally returned to the United States from her studies in Jordan, she says the people who were initially against her travel plans were surprised to see her return unharmed.

“There was genuine shock that nothing happened to me and that Amman was a safer place than they expected it to be,” she says.

Simmons says she used her experiences in Jordan to educate her concerned friends and family to the realities of traveling to the Middle East.

“The biggest thing I keep saying to my family is that it is just like here,” she says. “They have a huge idea that it’s all very Bedouin still or that the Middle East is still in the desert and people are traveling by camel. People there still drive cars.”

Mahfoudha al-Balushi had to dispel stereotypes in many of the conversations she had with Eugenians as well, but she says she was not discouraged by the interactions.

“You have to be very patient and explain what’s happening in your country,” she says. “You cannot just say, ‘No, my country is peaceful,’ you have to show them pictures and chit chat with them. You cannot change everything, but at least teach them something about your country.”

When it comes to really addressing the issue of the Middle East single story, Mahfoudha al-Balushi and Mohamed al-Bulushi agreed that the key is for people to travel and experience the different Middle Eastern countries for themselves.

“Don’t judge a book by its cover. You have to go. If you come to Oman and we know, we take it as our responsibility to take care of you. We invite you to our home, we host you, we give you some coffee and fruit, this is a traditional thing,” Mohamed al-Bulushi says.

Mahfoudha al-Balushi explained that this practice of welcoming visitors is grounded in Omani culture. “We welcome people from any part of the world. We don’t mind inviting people over for coffee or food. It’s the culture. It’s how we were raised,” she says. “As a person and as a human being, you really need to experience it for yourself. You need to travel.”

Abdulaziz al-Balushi wearing traditional Omani clothing. The hat al-Balushi is wearing is called a kuma and his robe is called a dishdasha. Omanis wear a kuma and dishdasha for just about every occasion. Photograph by Payton Bruni.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)