Story by Stephen Frey

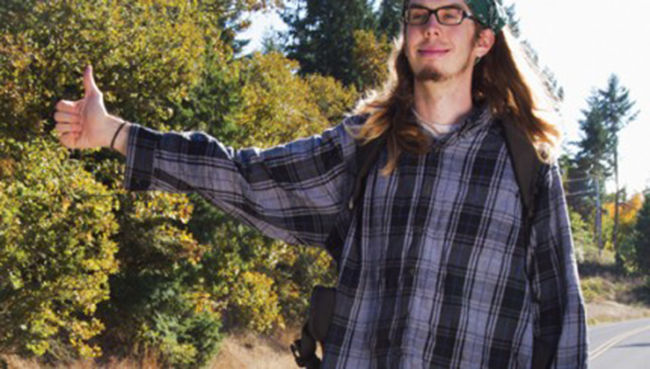

Photo by Emily Fraysse

When I was 19 years old, I walked out of my front door in Portland, Oregon, with a small backpack full of books and underwear. No money, minimal planning. It wasn’t running away from home; it was a personal experiment to form a new way of seeing things. On my way out, Mom gave me a $10 bill, “to buy some granola bars or something,” which I quickly disposed of in a neighbor’s mailbox. I walked to the southbound I-5 freeway and stuck out my thumb. I continued hitchhiking into Mexico and eventually passed through 11 Latin American countries until I reached Santiago, Chile, nine months later.

This peek into my old travel journal picks up several months after leaving the US. I’m on the outskirts of Panama City trying to get to Colombia. My possessions consist of a backpack, a hammock, and $48 that I saved working odd jobs in Panama City. There is no road between Panama and Colombia, so to continue my journey I need to hop a ship southward.

June 13, 2010

After a few hours of waving my thumb on the side of a two-lane road connecting Panama City and the Caribbean coast, I am delighted when a semi-truck slows and pulls off to the shoulder. The driver and I chat until he drops me off in the port village of Miramar. Here, the locals inform me that merchant ships never accept extra passengers, much less tall, blonde, eccentric-looking, backpacking gringos like myself.

I march to the dock. The air smells like crisp, salty seaweed left by the tide to dry under the hot afternoon sun. Only one small ship remains in the harbor. There are four short Kuna men wearing denim shorts and baseball caps, busily carrying boxes onto the ship.

Clenching my teeth, I pick a box from the pile, and stack it next to the others on the ship. The sailors seem indifferent to my presence, so our work continues in dedicated silence.

Once all the cargo is loaded, an older man, apparently the captain, emerges from the ship and asks what I am doing. I request to work on board in exchange for passage to the Colombian port city Puerto Obaldia. He frowns, glances curiously at my mud-caked backpack, shrugs, and says, “Why not?”

Yes!!! This is the ticket to South America! I toss my backpack onboard. The crew glares at me as if I am a landlubbing hobo who doesn’t belong here. Well, that’s true.

The ship’s cook invites me to eat dinner with the crew, where he serves us beautiful steaming bowls of rice and soup. Swimming in my meal is the stinking carcass of some creature that looks like a crossbreed between a crab and a space alien. The cook laughs while I probe its spiny exoskeleton with a fork. After dinner, the crew members retire to their respective hammocks. The sunlight has almost faded.

June 14, 2010—day 1 at sea

That space alien was delicious.

Looks like this boat, the Algo Mera, will be my home for a while. The crew consists of the captain, cook, four other grunt workers, and a man with a clipboard. My job, like the other workers, is to throw and catch boxes. The clipboard man is a walking personality disorder with thick-rimmed glasses. He is in charge of counting the boxes we throw and scribbling on the clipboards.

Tomorrow we begin the route south to the Kuna Yala islands.

June 15, 2010—day 2 at sea

This rice pot is especially overcooked today.

Through the screeching sound of my tin spoon scraping away burnt charcoal crust, I hear faint reggae music from the handheld radio in the next room. A stack of plastic plates stained with ketchup and fish oil awaits me in the washing tub. My fingertips are slick with soapy residue. I glance around the small kitchen to make sure no one is watching, scoop up a weightless cloud of bubbles, and clap, sending an explosion of little white soap globs floating into the air. I smile to myself and look through the kitchen door.

Outside is the ocean and a rugged wooden dock. A green parrot perches on the thick nylon ropes anchoring the ship to the dock of the island Soskantupu. The beefy clipboard man paces down the platform. Before him stands a single-file line of indigenous Kuna women, each one holding a handwritten carbon-copy order form for crates of Pepsi.

“¡GRINGO!” Clipboard Man calls to me. “¡Saca doce cajas de Pepsi! Llevalas aqui.”

“¿De donde?” I set the rice pot and spoon aside.

“Alla.” He nods towards the cargo hold below deck.

Scurrying out of the kitchen and down the ladder into the dimly lit hold, I rummage through heaps of cardboard packages and heave the boxes of Pepsi skyward. Counting as each box surfaces, the crew passes the cajas de Pepsi across the ship and to Clipboard Man, who stacks them. “Ocho, nueve, diez … diez, todovia falta dos cajas … once, doce. Bueno, ya listo.”

A light rain begins. The Kuna women remain poised, staring straight ahead. For a moment I am captivated as the rain droplets bounce off seawater. The rain reminds me of my home. Staying safe inside my house, I think, I never could have imagined being anywhere as strangely beautiful as here. I wish my family could see this.

June 18—day 5 at sea

Early in the morning, before the sun comes out, I climb to the kitchen roof to lie on the plastic tarps. The bow of the ship nods left and right, absorbing the calming rhythm of the waves. The ship’s gritty diesel engine chugs underneath the cold iron deck. A dense jungle of vines and ferns on Panama’s mainland coast passes on the starboard side of the ship as we head southeast through the Kuna islands that pepper the coastline.

Merchant ships like the Algo Mera are the remote islands’ only physical connection to the rest of the world, delivering products from the industrial mainland. Before this trip I had some romanticized idea about the Kuna tribes still living untouched by the Western vending machine diet. As it turns out, the Kuna also enjoy eating packaged foods from factories in Costa Rica; the plastic wrappers line the beaches like shiny seaweed.

June 20—Day 7 at sea

Today Panama celebrates Dia del Padre, one of those holidays for which the original meaning has become mostly irrelevant. The modern purpose is, of course, to get madly intoxicated. Many who want an early start (such as our ship’s cook) will take the day off work to ensure they are drooling and stumbling around half-naked before suppertime.

In the afternoon, I climb over the rusty sun-baked metal railing of the ship and walk down the concrete dock. Looking over the endless water from the island shore, I feel as though I’m standing on the rim of a contact lens floating in a swimming pool.

The soft skin of my toes feels the ground change from concrete to pebblestone to sand to soil. The footpath winds like an ant trail through palm groves into a blooming grass field, speckled with bright violet patches of wildflowers. The humid air swirls with intoxicating smells of tropical spices.

I wander into a neighborhood of Kuna houses neatly made of thick yellow and brown mangrove wood. Here I meet a group of about ten children, who spend an hour or so interviewing me about my favorite soccer players, if I have a wife, and all the animals that live in my home country. Feeling satisfied, they invite me to play beisbol.

CRACK. The bat, a two-by-four with a nail poking out, collides with a blue rubber ball and sends it soaring over the grass-thatched rooftops. The child tosses the bat aside and sprints toward first base. The other kids shout for him to run home: “Go ohm! Go ohm!”

Our beisbol game rages on until it is too dark to play. The grown-ups are still celebrating Dia del Padre. I follow flute music and soon the swarm of children leads me to a large clearing in the middle of the island. A generator sputters nearby. A yellow floodlight roped to a towering palm tree illuminates a central circle. An explosion of movement comes as a chorus of 25 colorfully dressed performers springs into the light and begins to dance. Panpipes penetrate the misty blue night air with sweet melodies. The faces of the dancers are radiant and for a moment it seems that an entire constellation of dazzling stars has come down to dance for this little island. A few hours pass. The light, dusky drizzle intensifies to a soggy tropical downpour, and I head back to the dock passing by huts lit by silver moonlight. On the ship I pull my feet back over the rusty iron railing, crawl over cajas of beer cans toward my hammock, and breathe in the familiar, lingering smell of burnt diesel.

June 21

After working eight days on the Algo Mera, this island is our last delivery. I curl my fingers around my last crate of Pepsi, and give it a slight hug just for good measure. By nightfall we arrive in Puerto Obaldia, Colombia. The crew of the Algo Mera leaves me alone on the dock, just as they found me. I step onto a new continent with nothing but my backpack and my memories. Tomorrow I’ll continue down the Pan-American Highway, following the road south.

On shore I lie down in an empty field and feel the breeze. As the cool, clear air above hums with stars, I straighten my spine, spread my arms, and listen. It is in these odd little moments that I feel as if the whole universe is surging through my fingertips. As I travel and connect myself with my ever-changing surroundings, the only direction I have really been going is inward. As the Kuna dancers’ feet skipped through the sand, I felt my body wanting to move with them. Like our little ship, I am a pilgrim adrift, a speck of dust floating in the sky, suspended among a magnificent swirling dance of dust specks.

People ask me about hitchhiking through other countries as if it’s a disease: “Isn’t it dangerous? Why didn’t you die?” For me, hitchhiking became the practice of tapping into internal resources while experiencing external scarcity.

This trip ended more than a year ago, and today where I’ve been is not as important as the way I continue to live my life. Amidst my day-to-day routine at the University of Oregon I must remember to regularly have spontaneous little moments of wonder as if I am still traveling.

And sometimes, just to keep the wind in my face, I still hitchhike up the freeway to visit my family.

Categories:

Destination Unknown

January 9, 2012

0

Donate to Ethos

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Oregon - Ethos. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover