She didn’t quite understand what she was watching. Sitting in her childhood home outside of East Berlin, Katharina Jones watched an East German official fumble through the announcement: The Berlin Wall was open.

The late evening news reported that people were moving towards the border. It started as a small trickle of people, unsure but hopeful that what they had heard on the news was true. Unprepared border guards turned them away at first, but people kept coming.

Soon the trickle of people would turn into the largest celebration the world has ever seen.

Jones woke up to her father’s whispering the next morning. She says he beamed with excitement in the darkness. Hearing the news in her father’s voice, it finally resonated with her. She could now travel freely between East and West Germany.

In the early morning hours, they drank champagne to the sound of the radio.

After celebrating with her father, Jones headed off to her early-morning nursing shift. Even at work, everyone’s eyes followed the news on television screens. While she was at work, her younger siblings had already entered West Berlin without even showing their identification cards. The barrier of applying for a visa, paying fees and going through interrogation in order to cross into West Germany was gone.

At the end of their work day, Jones and her family walked the Bornholmer Strasse bridge, one of the checkpoints in the Berlin Wall. On the bridge, Jones could barely move with so many people headed towards West Berlin. The stench of gas-oil exhaust from the East German Trabant cars trying to cross remains with her to this day.

On the other side of the Wall, welcoming West Berliners awaited. People greeted each other with hugs, laughter and tears. They drank and danced with strangers as if they were old friends. People exchanged their stories with each other. Previously intimidating and removed police officers became friendly and joined the celebrating masses.

It was a party for the birth of a new Germany.

Geteilte Deutschland

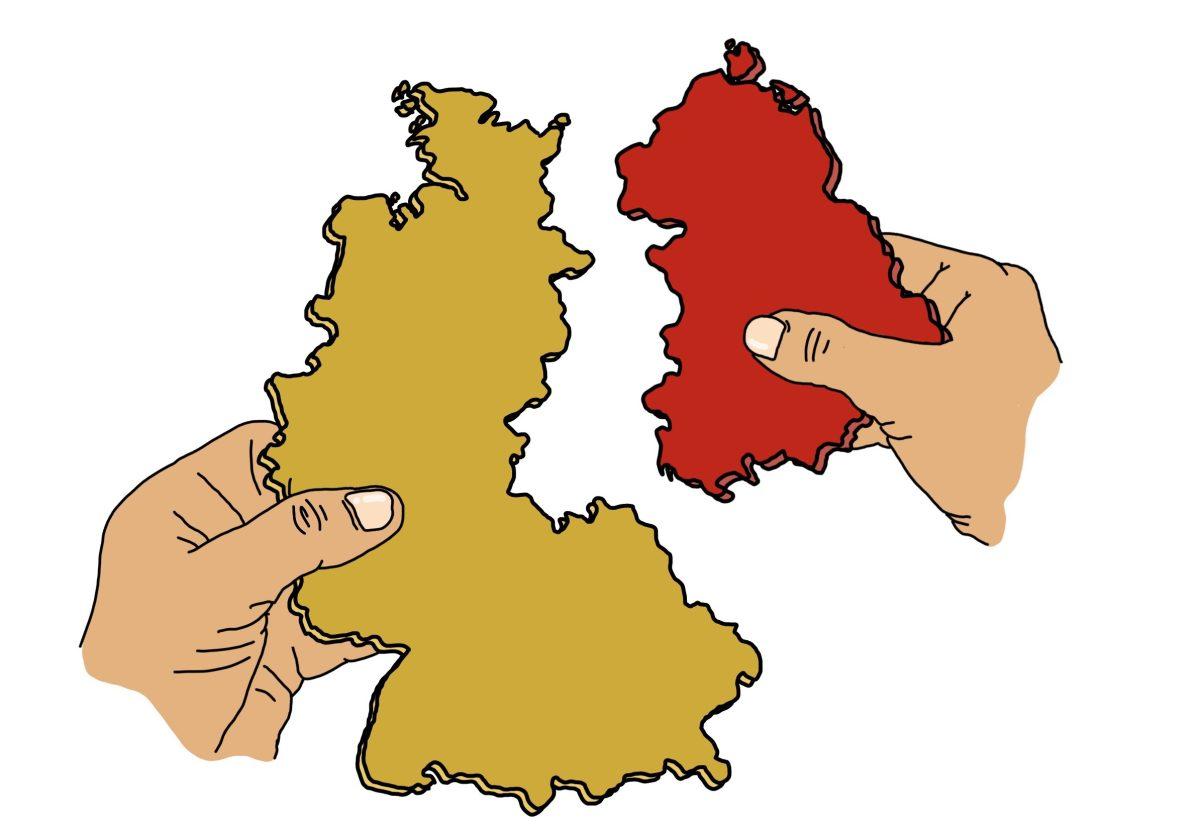

After World War II, with Germany defeated, the Allies decided that they would split the country into four zones, each occupied by one of the Allies. Although Germany’s capital was in the East, Berlin was also split into four by the Allies. Seven years later, in 1952, the U.S.S.R. decided to close the border between West and East Germany, officially setting up the Iron Curtain that divided the capitalist and socialist powers.

Losing their ability to travel to the West, many East Germans turned to the more accessible West Berlin. To stem the East Germans leaving the country, the German Democratic Republic (GDR) started constructing a wall that divided West and East Berlin in 1961. The Berlin Wall, which stood for 28 years, was a symbol of the Cold War tensions between the capitalist West and the communist East.

For Jones, who was born in East Germany in 1970, the fall of the Berlin Wall would disrupt her life in ways that she never predicted and that would last beyond her time in Germany.

Leben im Osten

Jones grew up in the small rural town of Schwanebeck-West, right on the outskirts of East Berlin. Her life was normal by East German standards. Like most, Jones secretly watched West German television. Despite seeing glimpses of the West on television, Jones grew up knowing that she’d never be able to see it in real life because of East Germany’s strict travel regulations.

In East Germany, the most important rule to follow was supporting the GDR. One’s livelihood depended on it. Lack of support could result in threats of unemployment, limited access to education and arrest. If people were critical of the GDR, they tended to criticize in private because the stasi, the GDR’s secret police, could be listening in. Growing up with these restrictions, Jones says they felt natural.

“There was this kind of control on everything you did,” Jones says. “We used to joke that in our country that everything that was not specifically allowed was forbidden.”

While Jones grew up tiptoeing around the limits of East German life, she was free to speak her mind at home. Criticizing the GDR was a common conversation at dinner in Jones’ house.

Jones’ father, Wolfgang Meiske, was a critic of the GDR. Born to working-class parents in Berlin, Meiske identified as a communist in his youth. He was barely entering his twenties when the Wall was built. As he grew older, he became disillusioned with the GDR’s promises and cut ties with the party. He preferred to think for himself and encouraged his children to do the same.

Meiske’s critical and independent qualities passed off onto Jones. Like her father, Jones grew critical of the GDR. She constantly saw flaws in the East German system and wanted to change them. She dreamed of a better socialist state that could give people good lives and security.

“She was quite independent in her way of thinking and what she wanted to do,” Jones’ sister Dorothea Meiske says.

Jones wanted change in the GDR because she couldn’t imagine herself living the same life that her parents had. While she loved her family life, Jones felt that the traditional path was not for her. She longed for a place where she could feel at home. In East Germany, the limits made it difficult to find that comfort.

“I was sure I would not spend my life in that narrow country,” Jones says.

Die Wende

After moving to East Berlin when she was 18, Jones was quick to join the opposition movement. Through a connection with a friend, Jones joined an oppositional group called the Umwelt-Bibliothek (Environmental Library), which was concerned with the environmental damage caused by the dated industrial practices in the GDR.

Jones worked as a librarian, keeping track of the Umwelt-Bibliothek’s collection of prohibited books and information about the environmental issues in the GDR. Jones also wrote a few articles for the group’s newspaper Umweltblätter, which spread information concerning politics and protests.

Housed in a church, the Umwelt-Bibliothek stayed just outside of the GDR’s reach, and it quickly became a hub for the opposition movement that led to the fall of the Wall.

While Jones says she believed in the mission of the group, she also joined because of the thrill of being part of a movement. It made her feel alive. These were the people that made the news and pushed for change in the GDR. They were outspoken and self-confident, qualities that she wanted herself. At times, Jones was even intimidated by some of the group members’ confidence because these were not qualities that were encouraged in the controlled GDR.

“I definitely wanted to be part of the change, but I also wanted to be part of these cool people,” Jones says.

In the months leading up to the 40th anniversary of the founding of the GDR, Jones says she basically lived in the Environmental Library. The church floors became her bed and organizing opposition demonstrations became her job.

Just like her group, there were others just as unsatisfied with the GDR. After the revelation of a fraudulent election in May 1989, people began fighting back against the GDR harder than they had before. East Germans wanted civil and political rights that they had been deprived of for 40 years.

By autumn, tensions built up as demonstrations occurred regularly throughout the country. East Germans were growing restless, demanding the same rights and living standards that people in the West had.

Jones says that it was clear that the police would come down hard on the protesters on the anniversary of the GDR’s establishment. She was scared of the dangers of protesting in the street. She knew the police would not hold back on using force and arrest.

When the anniversary came, Jones watched the protests inside the Environmental Library, where she took care of the injured protesters and helped organize the demonstrations.

Despite the police’s force, the protesters planned even larger demonstrations for the next few days expecting even fiercer reactions.

On October 9, two days after the GDR’s anniversary, young East Germans gathered for the demonstration. It steadily grew, but the protesters didn’t meet the same resistance that they had days before. Jones was experiencing a new freedom with her fellow East Berliners.

“We could all of a sudden go out and speak our mind, which was a totally new experience,” Jones says about the October 9 demonstrations. “If you grow up with that, it kind of goes without saying, but experiencing it as a gift was quite special.”

October 9 marked the beginning of the end of the GDR.

Mauerfall

About a month later, people flowed towards the Berlin Wall after the unexpected announcement that East Germans could travel freely to West Germany.

The GDR originally planned to allow regulated travel between West and East Germany because of the increased social pressure. However, with little information at hand, East German party official Günter Schabowski gave an improvised answer to a journalist’s question about when the new travel policy would take effect.

“As far as I know — effective immediately, without delay,” Schabowski said after scanning his note for the right answer. On November 9, 1989, with his answers, people began moving towards the Wall.

When Jones arrived in West Berlin, she was overwhelmed by the colorful billboards and noise of the other side. West Berliners warmly welcomed the crowds flowing in. It starkly contrasted to the gray quiet that Jones was used to in the East. While she had seen glimpses of life in the West on television, seeing it in real life was a completely new experience.

Jones, in the midst of celebrating, felt both freedom and grief.

She knew that imminent unification would give her freedoms that she didn’t have before. She could speak her mind and choose her occupation. She could also travel out of the country like she had wanted to for so long.

“It meant more freedom, even if that doesn’t mean that everybody feels better or that everybody is better off,” Jones says.

At the same time, she knew that the work of the Environmental Library and other groups like it would come to an end with the open borders. They were just starting to make progress in the GDR. With the newly open borders and expectation of reunification, it was clear that the more wealthy and capable Western system would take over in the East.

Dorothea Meiske, who was in high school at the time, was excited by the newly opened borders. Like Jones, she hated the travel restrictions in East Germany. But in the months leading up to the fall of the wall, Dorothea joined the demonstrations resisting the GDR without much concern for the consequences. She hoped that these demonstrations would bring about the change that she already felt coming.

“It was a lot of uncertainty,” Dorothea says. “For me, in a good way. Things that felt so stuck, so it is forever, kind of shifted suddenly. There was a lot of possibility and a lot of hope.”

In school, the students no longer took the pre-army training seriously. The pre-army training was a crucial step in career development in the GDR, but Dorothea says that it felt like they were on the verge of disappearing. The GDR was losing its grip.

“Even so with all the things building up, we didn’t expect that. And it was not even what anybody was fighting for because nobody believed it. We were fighting for a little bit of freedom,” Dorothea says. “I don’t think anybody really imagined that it would just be open. So fast. Or at all.”

Unlike Jones, her father was ecstatic that the Wall fell. Having grown up in a united Berlin, the establishment of the Wall deeply touched people in Jones’ father’s generation. Jones says that in the time before the Wall came down, her father told her about a dream where he was walking in a demonstration, surrounded by young people. In the dream, he had trouble keeping up with the crowd, but instead of falling behind, the people around him took his arms and supported him, carrying him along with them.

Ossis und Wessis Treffen Sich

The celebration continued for about seven days after the Wall fell. The ecstasy of this historic moment would quickly fade as the rashness of the fall kicked in and people from both sides became overwhelmed.

“First, it didn’t come so fast. I mean, we could go to West Berlin and come back,” Jones says. “But then it came to us.”

Jones remembers the day when the GDR adopted the West German currency, the stores had changed overnight. She stood in front of the shelves, not recognizing the new colorful products from the West. The plain East German products could not compete with goods from the West.

The everyday products East Germans would use were no longer on shelves, and small things such as using money and phone booths became difficult.

Sending in applications and going to interviews to convince someone to hire her for a position was completely new. It was strange for East Germans like Jones, who came from a system that guaranteed them jobs.

“They did have the security of a cradle-to-grave minimal social support system,” Peter Laufer says. Laufer is a journalism professor at the University of Oregon and worked as a journalist in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell. “They could get education. They could get a job. And they could eat, even if they were not the choices or the quality that was on the West side.”

The quick union of the two countries’ economies left thousands of East German professionals unemployed. And everything that East Germans had owned in the GDR became subject to new rules, causing many of them to lose their properties and security.

“That part was really awful, especially for the generation of my parents,” Jones says. “My father sent out, I don’t know, hundreds of applications because all of a sudden his position was endangered.”

While official German reunification was still months away, the process began with the people. Neither side was ready for the other.

While West Berliners initially welcomed people like old friends, the influx of people became too much for the small piece of the West in East Germany. Laufer describes the prejudices that grew in the months following the fall of the wall in his book “Iron Curtain Rising.”

“The new crowding was soon deplored,” Laufer writes. “The shabby dress and naïve window-shopping of the East Germans were derided by sophisticated West Berliners.”

Jones also quickly experienced the prejudices that came with reunification. Once, while she was working as a nurse, a patient’s daughter stood by complaining to Jones about how lazy and deceptive East Germans were. Meanwhile, Jones was lifting the woman’s mother from a hospital bed to a chair.

“After the Wall came down, they wanted to be full, accepted, real Germans, but they felt like second-class Germans,” Jones says. “That feeling had always been there in the way we grew up.

As she began to interact more with people from the West, Jones says she found some Western habits to be cold and frustrating. In East Germany, it was natural for friends to spend all their time together without talking about it. In the West, friends were more independent. Jones observed this individualism in how each person would pay for themselves when going out to eat in West Germany.

“That would not happen in East Germany,” Jones says. “ Our East German style was sticky. Friends really stuck together.”

As much as Western culture frustrated Jones at times, she also sought out new opportunities she only had access to after the Wall fell. She looked at West Germans and tried to learn from their strengths while also keeping the parts of her that she liked. As she started working with West Germans, she found that she liked their drive and clarity.

“Later I found that there’s a lot to it that I actually really liked about their way of doing things,” Jones says. “They tend to be clearer often, more outspoken, more articulate and more open-minded.”

With the integration of the Western capitalist system came easier access to anything that Jones was interested in. Jones picked up books on topics ranging from philosophy to psychology. She also tried different jobs and traveled to different countries. She once lied about being an author to get a job creating movie audio for the blind. Another time, she ended up working for an environmental organization in Russia in the middle of the biting cold winter. She only stayed there for six weeks before returning home.

While many of her jobs never worked out for very long, Jones says she is grateful that she had the freedom to explore her options. Without the restrictions of the GDR, she could live a free life with all the good and bad that came with it.

“Looking back, I think that for me it was sometimes really hard,” Jones says, “but also deeply satisfying, in the hindsight, to try so many things.”

Mauer im Kopf

While Jones has since moved to Eugene, Oregon, she still keeps up with what’s happening in Germany. In the news, she sees the same problems that were there 30 years ago. There is still a divide between West and East Germany, even without a wall.

The adverse economic effects of reunification that occurred in the East have not been completely remedied. According to Laufer, East Germany still remains less developed than West Germany. After years of prejudice and the lack of development in the region, East Germans felt neglected by their own country. The feeling of being marginalized gave way to right-wing sentiments in the East.

“A lot of the far-right, anti-immigrant, racist attitudes that are exemplified by the political party Alternative für Deutschland, the AfD. It has a strong base in the Eastern states,” Laufer says.

Jones says she acknowledges the right-wing politics that have taken root in some of the East. Still, when she sees comments in the news that perpetuate East Germans stereotypes, she gets angry because she knows that it is not the whole story.

Jones remembers East Germans as being warm and close like her friends that she made in her youth. She remembers them as capable and smart like her father. And she remembers them most of all as strong for resisting their government, both quietly and out on the streets.

Jones knows that the scars that the Wall left behind on the German people are still healing.

“You have these huge differences and you cannot just say ‘Okay, let’s make it all equal,’” Jones says about the divide within Germany. “It takes time. It takes generations.”

Art by Eleanor Klock

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)