Warning: This story contains descriptions of child abuse

Soon after Marty* retired, the nightmares started. He’d jolt awake from them in a frenzy. Sometimes, he’d be so anxious that he’d throw up.

That was 10 years ago. Marty is 72 now.

“When they first started happening, I couldn’t even remember what the hell they were about,” he says. “All I knew was that I would wake up in this mentally wrecked state of mind.”

Marty struggled with depression and anxiety for most of his life, but the nightmares brought him to new levels of misery.

Marty’s biological mother died in a car crash when he was four years old, and his father remarried. Marty had two stepsisters, but he was the only sibling from the previous marriage. He says his stepmother especially targeted him for being the “foreign child.”

She started beating him when he was seven, and kept beating him regularly until he turned 16 — that’s when he moved out of the house.

He went to counseling soon after the nightmares started, but he couldn’t figure out what they were about or why he was having them. His therapist couldn’t either.

Then four or five months after the nightmares started, he started remembering them.

“They were just my mind going back to childhood situations,” he says. His mind was unoccupied with work now that he was retired, and dark memories from the past emerged from the murky waters of his subconscious.

He describes a recurring nightmare.

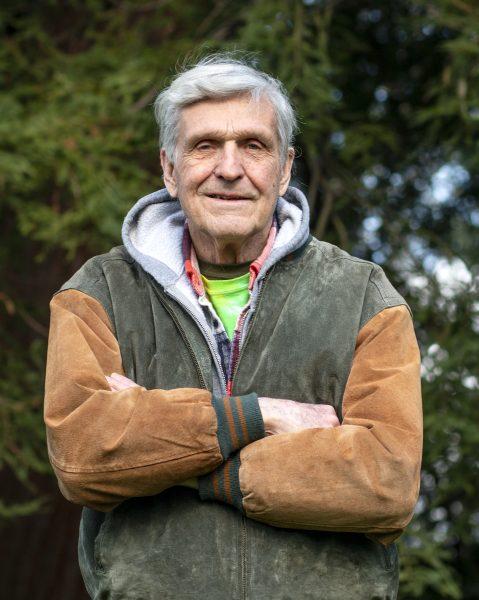

Marty’s stepmother began beating him at age seven and continued to do so until Marty moved out of the house at age 16. The years of abuse left Marty with depression, anxiety and PTSD. Marty says that psilocybin mushrooms have helped him find happiness and work through his trauma more than prescription antianxiety medication or antidepressants ever did. (To maintain anonymity and privacy, Marty’s real name and identity were withheld from these photos per Marty’s request.) Photo by Payton Bruni

Marty’s stepmother began beating him at age seven and continued to do so until Marty moved out of the house at age 16. The years of abuse left Marty with depression, anxiety and PTSD. Marty says that psilocybin mushrooms have helped him find happiness and work through his trauma more than prescription antianxiety medication or antidepressants ever did. (To maintain anonymity and privacy, Marty’s real name and identity were withheld from these photos per Marty’s request.) Photo by Payton Bruni

His stepmother was interrogating the kids about makeup powder that was dusted on the bathroom floor. Like always, his stepmother was picking on Marty more than the others. She took him into the garage, to his “beating spot.” He stood in the three-foot gap between the washer-dryer and the car, a black-and-yellow, 1957 four-door Chevy.

“She just started pounding on me and pounding on me and pounding on me until I caved,” he says. He told his stepmother he’d spilled the powder, even though he hadn’t.

“Hell, I was only seven years old.”

Marty’s voice is packed with emotion as he speaks. It happened 65 years ago, but he’s replayed the situation over and over in his head.

His little sister was the one who’d spilled the powder on the floor to spite her mother, but Marty didn’t know that while his stepmother was beating him — he only found this out five years ago.

While he is open to talking about being abused as a child now, he kept his trauma to himself for almost 60 years.

“I was married the first time for 13 years, and I never told that woman. And after that, I was married again for 24 years, 11 months and something days, and I never told that woman,” he says. “It was buried,” he pauses. “That’s a burial job.”

Marty attributes his newfound openness to a new habit — eating mushrooms containing the psychedelic drug psilocybin every day.

Since he started taking the mushrooms in August 2019, he says he’s been feeling happier. And he’s made strides in working through his depression, his anxiety and his PTSD from child abuse.

“I’m more open, straightforward, more present, more grounded,” Marty says. “I can laugh at my bad attitude now.”

There’s only one issue. Psilocybin, the psychoactive substance in mushrooms, is federally a Schedule I drug, on the same legal level as heroin, ecstacy and LSD — substances the Drug Enforcement Administration says have no accepted medical use and high potential for abuse.

People have been using psilocybin for thousands of years. Researchers found sculptures of psilocybin mushrooms at archaeological sites in Mesoamerica dating back to 500 B.C. The oldest archaeological evidence shows that humans have been eating these mushrooms for over 10,000 years, according to a paper by ethnobotanist Georgio Samorini.

And recent studies show the drug’s potential for treating PTSD, anxiety, depression and substance abuse. So scientists, psychologists and activists are pushing to get psilocybin decriminalized, legalized or licensed for therapeutic use in the U.S.

Last year, psilocybin was decriminalized in Denver, Colorado, and Oakland, California. In Oregon, two bills relating to psilocybin may be on the ballot this year: initiative petitions 44 and 34. If passed, 44 will be the first to decriminalize psilocybin on the state level in the United States, and 34 will be the first to license it for therapeutic use.

Psilocybin is not physically addictive, according to Michael Pollan’s 2018 book, “How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence.” It’s also nearly impossible to die from an overdose of the drug.

But “bad trips” sometimes happen. These experiences can be psychologically scarring and can damage mental health instead of making it better. However, bad trips normally stem from being in the wrong mindset for a trip or the wrong environment. And since psilocybin research restarted in the 1990s, people have been given more than a thousand doses of psilocybin, and nobody’s mental health has been harmed, according to the book.

Initiative Petition 34 would try to create treatment centers where licensed therapists could prepare patients to minimize the risk of a bad trip. The bill would just allow the drug to be administered inside these facilities during guided treatment sessions.

Patients would be given large doses of psilocybin in licensed centers. Licensed therapists would then lead them through an intense trip intended to break behavioral and mental loops of depression, anxiety, addiction, trauma and fear. They’d be screened to make sure they’d respond positively to psilocybin before a session. They’d be briefed and prepared for the trip. And they’d be debriefed afterwards, to talk about how they can revisit the experience to use the trip to change themselves.

“While there are many different reasons people could potentially benefit from psilocybin therapy,” Initiative Petition 34 Spokesperson Sam Chapman says. “It’s not for everyone, and we’re not pretending it will be.”

If passed in November, there would be a two-year planning period before it took effect. In this period, the governor would create a board of experts who would make recommendations to the Oregon Health Authority on rules that should be included in the law.

Oregon is the second-worst state in the country for mental health and addiction services, and psilocybin could be a good tool to help fight the mental health crisis, according to a press release provided by Chapman.

Initiative Petition 44 would decriminalize noncommercial possession of all Schedule I, II, III and IV drugs, and replace criminal charges with small fines. It would also re-appropriate funds from state marijuana taxes to fund addiction treatment centers for those found with drugs.

Canvassers are currently collecting signatures to get the bills on the ballot. In Eugene, signature-gatherers have been stopping students outside the Erb Memorial Union and on 13th Avenue near campus. They’ve been talking to people outside of grocery stores and restaurants around Eugene. The deadline for submitting signatures is July 2.

At Johns Hopkins University, researcher Roland Griffiths and his team at the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research have been conducting psilocybin therapy sessions since 2000, similar to those that would be conducted in Oregon if the initiative passes. According to the center’s website, research has shown that psilocybin has therapeutic effects in people who suffer from addiction and treatment-resistant depression. Researchers at the center administer large doses of psilocybin in their trials.

Marty only takes small amounts of psilocybin, around 0.1 grams per day. This is less than a tenth of a regular recreational dose and a thirtieth of the doses given in psilocybin therapy. The technique is called microdosing. He grinds the mushrooms into a powder. He mixes it into melted chocolate and makes little chocolate squares. He nibbles the chocolate through the day.

But the results that Marty has had from microdosing are similar to those that people who’ve been in trials at Johns Hopkins have experienced: breaking out of patterns, reducing dependency on substances and seeing old issues in a new light.

“I still think these things are the greatest things since sliced bread,” Marty says about the mushrooms. He takes a prescription bottle out of his bag, opens it and shakes a couple of squares of psilocybin chocolate into his hand. He puts the chocolate back in the bottle and snaps the lid shut.

Author Michael Pollan says that psychedelics can help people to see their own behavior in a new light.

“The camera on the scene of your life gets pulled back to a new height and you can see the absurdity of something you’re doing,” he says about taking psychedelic drugs.

Under the influence of psychedelics, he says, old truths, like “cigarettes are bad for you,” take on a new authority that can lead to change. In Marty’s case, he realized how past trauma was causing him to act now. By seeing the pattern clearly, he was able to break it.

“Psychedelics lubricate cognition, it just relieves you of that set of connections that you keep falling back on,” Pollan says. “And at least temporarily, new connections form.”

In Marty’s case, he says psilocybin has helped him become more open to other people. He says it’s helped him reduce his dependency on marijuana. And he says it’s helped him work through his PTSD from child abuse — something he’d carried around his whole life.

Before trying mushrooms, Marty went through a medicine cabinet’s worth of antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs. But he says none of them helped him work through his issues.

Marty also smoked through pounds of marijuana to keep his issues at bay. He says he’s struggled with a need to use substances his whole life.

He says he thinks he would have been an alcoholic if he didn’t have celiac disease, which makes him unable to drink.

“But I smoked the shit out of weed for 50 years,” he says.

Marty says microdosing has made him less dependent on cannabis. He smokes half of what he used to. And Marty says he doesn’t feel like he needs to take pharmaceutical drugs anymore.

Sharon Newton, who’s been friends with Marty for 10 years, says he seems more relaxed and outgoing in social situations than he used to be. She says he would be in “a deep, dark hole” right now without them.

Newton also says she’s noticed Marty change in other ways. Back when she met Marty, she noticed he’d hunch up his shoulders when he got excited while he was talking. Newton thought it was creepy at first.

“Then I figured it out. It was because he was flinching, expecting to get hit. After years of doing that all the time, it becomes the natural thing for you to do,” she says.

Since Marty started microdosing, he says he’s been able to stop himself from hunching. He says he can see patterns of behavior caused by his PTSD now.

While Marty has used psilocybin as a balm for his mental health, people have been using the drug for other purposes for thousands of years.

The Aztecs ate psilocybin mushrooms as a religious sacrament, calling it teonanácatl, or “flesh of the gods,” according to Pollan’s book. It was their method of having mystical experiences that connected them to the divine.

Pollan writes that in the 1960s, hippies used psilocybin and LSD to break out of the strict cultural norms of the 1950s.

Ken Babbs is a member of the Merry Pranksters, an LSD-taking counterculture group whose trip across the country in the school bus “Furthur” was memorialized in Tom Wolfe’s book, “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.”

Ken Babbs poses for a portrait at Washburne Park in Eugene, Oregon. Babbs, a member of the Merry Pranksters group, advocates the use of LSD and psilocybin mushrooms in an effort to better oneself. Photo by Payton Bruni

Ken Babbs poses for a portrait at Washburne Park in Eugene, Oregon. Babbs, a member of the Merry Pranksters group, advocates the use of LSD and psilocybin mushrooms in an effort to better oneself. Photo by Payton Bruni

Babbs says taking LSD and psilocybin helped him become a kinder, more open person, at an interview at his home he built out of pieces of an old barn in Dexter, Oregon.

“It changed me. I was a real dickhead when I was young,” Babbs says. “It changes your perception of how to be with other people and how to be yourself.”

“When you’re growing up, you’re imprinted with all this stuff that helps shape you, who you are. And it forms a screen in your head, right in here.” He taps his right temple with his forefinger and leans forward with his elbows on his worn wooden dining table.

“But when you take LSD, it blows that screen apart. And new shit is coming in,” he says. “And your mind is exploring places it’s never been.” He picks up the glass of red wine he’s drinking, takes a sip and sets it back down.

Carolyn Garcia, another member of the Merry Pranksters, was married to Jerry Garcia, the lead guitarist and vocalist for the Grateful Dead. She’s known as “Mountain Girl” in the Prankster crowd.

Using psilocybin has helped her be more present and find a new appreciation for nature, Garcia says. She describes the first time she took psychedelics.

Garcia was sitting on the ground under the redwood trees in Palo Alto, California, on a sunny day in 1964. As the LSD she had taken took effect, she looked down at the redwood needles below her and saw them rotating and swirling in little circles on the ground. She listened to the gurgling of the creek nearby, the wind rustling through the trees and the birds chirping.

Taking psychedelics has helped her connect to nature ever since, and it’s helped enrich her day-to-day life, she says.

Garcia says she supports people who use psilocybin for medical use, but she feels that Initiative Petition 34 is too narrow and should include licensing for uses of psilocybin that don’t have to do with therapy. The bill was revised last year to be more focused on therapy, a move Garcia doesn’t agree with.

“There’s too many people involved here who’ve been handling mushrooms for a long time all over the world, and to try to sequester that activity and hold it just to therapists in carefully monitored situations seems unfair,” she says.

For Marty, though, psilocybin use has been deeply rooted in therapy. And that’s what Initiative Petition 34 is about.

Marty says his romantic relationships all ended partially because he was unable to share his emotions. Not only was he not telling his partners about his PTSD from child abuse, he was also not telling them how he felt.

Marty says he remembers his first wife yelling at him, imploring him: “Tell me how you feel! Tell me how you feel!” But he couldn’t get himself to open up.

Then, about 65 years after his stepmom beat him in the garage, about 10 years after the nightmares started, a couple of months after he started taking psilocybin, he went back to his two ex-wives — and he told them about his trauma.

His first wife was shocked. She’d never expected something like this. But mainly, she was relieved. Marty says she finally understood why he could never tell her how he felt.

Marty was also relieved. He says telling her about his trauma was a key stepping stone on his path towards disclosure, ownership and acceptance.

His second wife was also happy Marty told her. He says she finally understood why Marty never knew how to fully love her — he didn’t console her even during her darkest moments, like when 9/11 happened.

He says psilocybin helped him tell them and everybody else about his child abuse, something that’s been essential to his recovery.

“The more times I tell this story, with more depth and detail, the easier it becomes.”

*Marty is referred to by first name only, per his request.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)