Dark gray and seven stories high, Barnhart Hall, University of Oregon’s designated quarantine dorm, towers over Patterson street. Sticky notes are pasted on many of its large, square windows. On a note on the window of Christian Binder’s room, the words “Fuck This” are spelled out for the passerbys below.

Binder was sent to Barnhart to quarantine for two weeks after learning his roommate tested positive for COVID-19. The rest of his room is bare and white, with snacks and school supplies cluttered on the two tables he has pushed together. Binder says after two days, he felt like he had been in Barnhart for an entire week.

Binder, and around 3,000 other dorm residents, arrived at campus this fall with hopes for some semblance of a normal college life despite the growing pandemic. With all of the chaos around him, Binder thought the close community experience of the dorms was exactly what he needed.

On Nov. 5, though, as he sat in his bare room in Barnhart, he felt torn about his decision.

Binder is one of thousands of freshmen across the country moving into the dorms despite the pandemic, hoping for a safe and fulfilling introduction to college. The value of dorm life during the pandemic is complicated and unclear for many of them. Seeing students get away with violating safety protocol can be disheartening for those feeling isolated as they do their best to stay safe.

Since June 1, 2020, 83 students living on campus have tested positive for COVID-19.

With a total enrollment of 22,760 students, UO has found 686 positive cases in students and faculty. In comparison, Oregon State University, with a total enrollment this year of 32,312 students, has found 272 positive cases in students and faculty. OSU’s dorms are also open.

Michael Griffel, UO’s Director of Housing, says he believes the dorms can offer a unique and engaging experience that at-home learning cannot. “During the pandemic, the residence halls are among the very few environments where students can make strong connections with a broad range of the students from across the country and globe, while following public health guidance,” Griffel says.

Back in March, the Oregon Health Authority sent out an announcement encouraging schools to “consider all alternatives before closing,” as they “recognize the instruction universities and schools provide is vital to student well-being” in addition to providing “many students their only access to healthcare and food.”

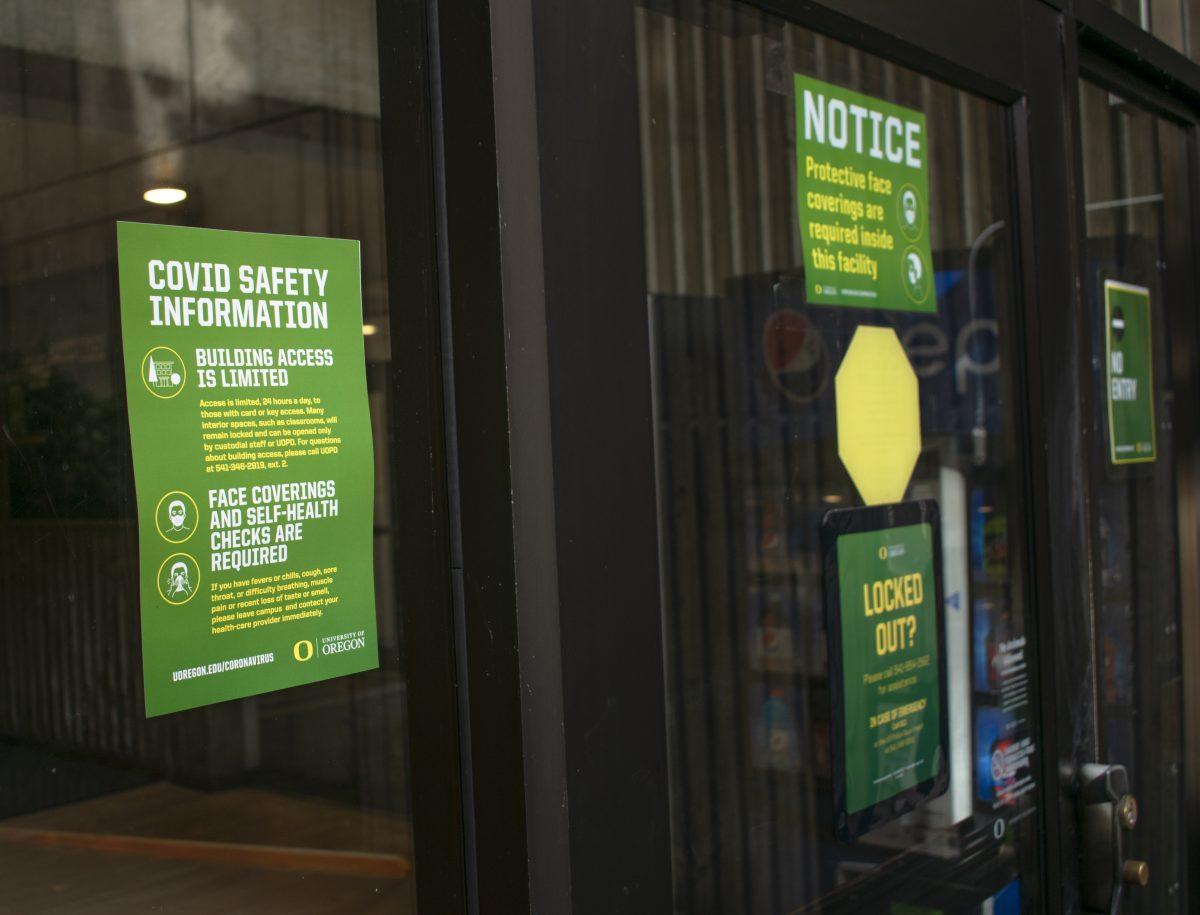

UO’s housing website says the school is doing everything it can do to ensure a safe experience. The site says, “We are committed to meeting, and in many cases exceeding, all of the standards and guidance from the Oregon Health Authority for our residence halls.” These standards are intended to be met through reduced density of residents, extra cleaning and not allowing more than two students to live in the same room.

Max Cronk, a student who lives across the hall from Binder, says UO has been “really proactive” about enforcing safety protocol. Cronk was written up for hanging out in another student’s room by a resident advisor, an older student who lives in the dorms with freshmen and makes sure they adhere to UO conduct. He says it was a learning experience that he needed.

“They had me read some research articles about COVID and write a response paper,” Cronk says. “It was a great way to reflect on the impact of my actions, and now I’ve been much more inclined to follow the rules.”

Binder, on the other hand, says at the end of the day, there’s not much the school can actually do to enforce their safety regulations.

“They can tell students to wear masks and not visit with each other, but that’s not actually going to stop people,” Binder says.

Students living on campus are required to get tested every other week for COVID. They conduct the tests themselves, inserting a cotton swab up their noses. Medical professionals supervise to ensure the samples are collected correctly. Binder says the whole process took 20 to 25 minutes at the beginning of the term but now only takes five to 10 minutes.

On-campus residents who test positive are sent to Barnhart to spend two weeks in total isolation. They are not allowed to leave their rooms at all. Students like Binder, who have come in contact with someone who tested positive, are also sent to Barnhart, but are allowed to leave their dorm for two hours every day. Food is ordered online and made in the dining hall on the first floor, which is then brought up to residents so they can remain in their rooms as much as possible.

Binder says the boredom of being stuck inside all day actually helped him get his school work done. “You get your schoolwork done and then you’re just like what do I do now,” Binder says. “There was nothing else to do. You just had to get used to it.”

After Binder’s roommate in his previous dorm, Living-Learning Center, received the call that he had tested positive for COVID-19, Binder had an hour to shove everything he needed for the next two weeks into two trash bags and rush to a van across campus. The driver dropped him off in front of Barnhart, gave him his room key and drove off.

“I didn’t even eat dinner that night, and I forgot a bunch of stuff since it was happening so fast,” Binder says. “There’s no soap or tissues here, but I didn’t even think to bring that.”

Binder says he used body wash and hand sanitizer in place of soap; he didn’t want to go out and buy any for risk of spreading COVID-19.

Students living in other dorm rooms are also encouraged to keep to their own rooms as much as they can, though unlike quarantined and isolated students, they are allowed to move around freely. Resident advisors were told to write up residents for hanging out in each other’s rooms, not wearing masks or violating the occupancy limits in communal areas. After two or three warning write-ups, violators can be told to leave the dorms, as agreed to in the contract students were required to sign before moving in.

But according to Jadon Faulconer, a resident advisor at Living-Learning Center, rules like that can be hard to enforce when he’s also trying to distance himself.

“It can be really anxiety-inducing to have to be on guard all day, looking for things I have to document,” Faulconer says. “That anxiety also comes from living with a lot of people that don’t seem to be taking the virus as seriously as I do.”

This is Faulconer’s third year as a resident advisor. He says that this year involves more work than before. On top of his typical duties, like monitoring drinking and maintaining quiet hours, he must now look out for all the possible safety violations, which Faulconer says many freshmen are struggling to follow.

“I think it’s really hard for people to adjust their preconceived notions of what their first-year experience is going to be,” Faulconer says.

Rodrigo Olvera, a resident advisor in the dorm Justice Bean, says he’s also noticed freshmen struggling to follow dorm protocols, but that there has been some improvement since the beginning of the year.

According to UO’s website, which has been charting COVID cases among faculty and students since June 1, there was a surge in positive results during late September and early October, just a few weeks after students first moved in on September 20.

“There was definitely an adjustment period for everyone that moved into the dorms,” Olvera says. “It took a while, but now they understand the protocols and are respectful of what is asked of them.”

Binder says he and many other dorm residents feel extremely conflicted about their decision to live on campus. He recognizes the danger but couldn’t help hoping that even a small look into “real” college life through the dorms would make it all worth it.

After losing big moments of his senior year in high school to the pandemic, Binder was craving actual change. To him, going virtual and cancelling graduation made a milestone in his life feel anticlimactic. He considered attending community college from his home in Virginia but decided that living in the dorms was something he wasn’t willing to give up.

Cronk says he also felt dorm life was a must for him, and stands by his decision to move in.

“Getting a fresh start and being in a new place was really something I needed to do for myself,” Cronk says. “It would be a totally different experience to be at home still.”

Determined to get the most out of his limited circumstances, Binder has made his own happiness in Eugene. He goes skateboarding as much as he can, visits the river and takes aerial footage with his drone. He’s also become great friends with his roommate. They often play video games together in their room and keep in touch while quarantining and isolating.

“My roommate and I are a perfect match,” Binder says. “We were both really excited to see each other after two weeks.”

While he’s very excited to have gotten some positive experiences from the dorms, they still don’t meet his original hopes.

If he could do it all again, having seen what the year would really look like, Binder says he probably would have stayed out of school for the year. Now that he’s already made it through one term though, Binder feels inclined to stick around and see if things will improve over time.

Students had until Oct. 15 to withdraw from the dorms and receive full reimbursement. Living in the dorms costs anywhere from around $10,000 to $20,000 per school year, depending on the specific dorm and meal plan. After that, students who left the dorms had to pay $9 a day for each day remaining in the contract. Students planning to live on campus for winter term have until Jan. 2 to withdraw with zero penalties.

Despite his concerns with safety and questioning how “worth it” the dorms are considering the cost, Binder plans on returning to the dorms after winter break.

Barnhart Hall has been reserved as the university’s isolation (for positive cases) and quarantine (for those exposed) center. Binder counted every minute of his two-week quarantine with very little interaction with others including staff. “We have to order our meals the day before, and then they drop them off at our door and leave,” Binder says. “We can’t even do laundry, and I’m running out of clean clothes.”

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)