On a warm and dry summer Oregon night, a left-handed Portland Pickles batter steps up to the plate. Hamlin Sports Complex, the Springfield Drifters renovated stadium, is decked out with fans covered head-to-toe in blue and white baseball merchandise, ready to cheer on anything that goes their way.

The Pickles batter fouls one off to the left, over the concourse and over Jamie Christopher’s head. Suddenly, an onslaught of young footsteps stampede the silence in a pursuit to find the foul ball. Comments like “be careful” and “walk, don’t run” emerge from the parents in the crowd. But for Christopher, the general manager of the Drifters, all he could do was crack a warm smile.

“That’s what this type of baseball is about,” Christopher says. “It was really where I settled in, and said ‘we’ve arrived’ and where we turned a corner.”

The Drifters are a summer baseball team made up of strictly collegiate talent. They play in Springfield, but they can recruit from schools all over the country. Aside from providing the community with high-caliber baseball, the Drifters are just a slice of the grand effort to improve sports in the community.

“This is really the first time in my life that I’ve ever gotten to wear a jersey with the words ‘Springfield’ across the front,” says Cade Crist, a catcher for the Drifters and Tacoma Community College who was born and raised in Springfield. “Everything in this area always says ‘Eugene,’ but this is different. It makes me proud.”

Several years ago, things were different. The Drifters, whose goal is to encourage kids to play baseball, weren’t around. The Springfield/Eugene area lacked widely accessible fields that also encouraged sports and physical activity. In terms of local youth, the impact this can have is drastic.

Two local business leaders, Ike Olsson and Kelly Richardson, saw this issue as an opportunity. Olsson, the president of Olsson Industrial Electric, and Richardson, the president and CEO of Richardson Sports, created a financial plan in 2019 to launch a complex at Hamlin Middle School in Springfield. They hoped that complex would become a hub for baseball from the middle school to the college level.

They created the Springfield Baseball Project, a foundation to broaden access to and participation in youth baseball. The first step was partnering with the Springfield School District to improve and establish connections, but one of the end goals was to turn Hamlin’s field into a stadium. This project also included the Drifters as a “forum to build a love for baseball,” Christopher says.

As news of the Drifters hit the Willamette Valley in early 2021, the West Coast League (WCL), which the Drifters are a part of, was expanding from 12 to 16 teams. WCL Commissioner Rob Neyer says they were looking to add another team in the Willamette Valley for a while, but they were just waiting for the right opportunity. Thankfully for him, Olsson and Richardson had already gotten the ball rolling.

The WCL is a 16-team collegiate wood bat league based in Oregon, Washington and British Columbia that features talent from all over the country. It aims to help student athletes prepare for wood bats in professional baseball, as opposed to the metal bats they use in college.

In order to ensure that the newly constructed Hamlin Sports Complex will be used to its full potential, the project also partnered with Bushnell University. The Bushnell Beacons will use the field in the winter and spring, the Drifters in the summer. The $3 million redevelopment included a newly turfed field, dugouts, a press box and seating for 2,000 fans.

Christopher says he hopes the Drifters and the year-long play at Hamlin Sports Complex can serve as a mecca for the Willamette Valley community for decades to come.

Christopher joined the Drifters in April, 2020, six months after Olsson and Richardson had founded the team. The Drifters were in need of baseball expertise in order to get the operations flowing. Christopher, who has spent a lifetime in baseball, checked all the boxes.

When he was hired, Christopher was met with a mountain of tasks to complete, from finding players to raising money to finding host families.

“It’s an astronomical amount of work to run a ball club,” says Eric Leyba, a Drifters fan and assistant coach for Oregon State Softball. “For one person to do it, there’s just so many moving parts. I think from where Jamie has started to now, he’s built an amazing foundation.”

To make it happen, Christopher started his days at 6 am and worked until midnight.

Working and leading up to the team’s official launch on May 31, 2022, Christopher and the rest of ownership maintained one common thread through all their endeavors: community.

“The goal of our organization, first and foremost, was to create a community hub that would benefit local youth,” Christopher says. “We really want Springfield to feel like their team. Anytime I write something online I say ‘your Springfield Drifters,’ because it’s really theirs.”

The Drifters teamed up with Huddle Up, a nonprofit that donates food, clothing and resources to food banks and underserved sports communities, at the beginning of the season. The nonprofit was formed just a few years ago when Olsson got private donations to build a softball field for a school in need. Now, Christopher has joined, and he and the rest of Drifters ownership donate to the nonprofit.

Since Huddle Up’s inaugural project, Richard Schwab Field at Maple Elementary in Springfield, the nonprofit has established connections with Springfield Public Schools, Timber Products Company and Richardson Sports, both local businesses. Huddle Up aimes to increase accessibility to youth sports, similar to the Springfield Baseball Project and the Drifters.

Aside from just donations, the relationship between the Drifters and Huddle Up is to inspire more kids to pick up a ball and bat.

According to the Novak Djokovic Foundation, sports teach kids morals and life lessons, create friendships, and build self-esteem, among other benefits. A lack of youth sports can impact a kid for much longer than just their childhood years, however. Aside from just the health cautions, a lack of sports can also deteriorate a child’s mental health, intensify academic behavior, and worsen one’s likelihood to attend college, according to Project Play. In Springfield, there were barriers to accessing these benefits.

“You think you’d see an increase of kids playing baseball with the Drifters, the Eugene Emeralds and two competitive baseball schools in Oregon and Oregon State, but unfortunately, you just don’t have enough baseball and softball people in the area,” Leyba says.

Leyba also co-owns a batting cage in Eugene called Coaches Athletic, and he says it gets customers from as far as Roseburg and Salem. As positive as this is for business, it puzzles Leyba and increases his concern for the future of the game.

While it has become the Drifters’ goal to help kids on the field, they’ve also inspired kids off the field.

Throughout the course of a game, several concession discounts and certificates are handed to kids who put their Drifters spirit on display by either dancing on the field or being the loudest fan.

“Before putting on a promotion in front of hundreds of fans, I’ve seen kids tense up and even get emotional out of fear,” says Jeremy Leung, a promotional intern for the Drifters and a UO student. “When they’re finished, and being applauded by those same hundreds of fans, the mood always changes. Seeing those kids smile makes the job 100% worth it. It’s amazing.”

The Drifters players themselves have also had a lasting impact on the youth community. While some players represent local schools like Bushnell or UO, others came in from as far as Hawaii in hopes of helping the team win a title. No matter where they’ve traveled from, players have similarly already found themselves to be hometown heroes for the kids.

“After a home game, our head coach’s two sons were on the field and asked me to pitch to them,” says Michael Soper, an infielder for the Drifters and Linn-Benton Community College. “As I started pitching to them, a couple other kids came and asked me to pitch to them. Then, a few more joined, and I was throwing to five to six kids at home plate. It felt cool to be the guy the kids wanted to play with because they looked up to me and came to ask me specifically to play with them.”

Like many other players, Soper stayed with a guest family all summer. Unlike anyone else on the team, however, Soper stayed with the Christophers. Over the course of the season, Soper bonded with Christopher and his son over their love for baseball, through family dinners and even country music, even though the Christophers say it’s not their favorite.

“I’ve dealt with nothing but good people and fans in my time here,” Leung says. “One of the most rewarding parts of the job is seeing the same faces reappear, sometimes with new faces each time. It makes me proud to work in such a communal environment and proud to work for the Drifters.”

Just before the end of the season, the Drifters held a two-day baseball camp led by players and coaches. Christopher plans to run this camp every summer. He also added that “if someone doesn’t have the funds to attend, we will let anybody in.”

The Drifters missed the playoffs and finished the year just 17-37, but the season was a much larger success than their record would indicate. On-field and off-field moments have given fans, the community and Christopher something to be excited about for the foreseeable future.

In the next five years, Christopher hopes to see consistent sell outs with a steady flow of season ticket holders and repeat customers. He added that a championship will come one day, but for now he just wants the community to get involved with their team.

“A few days ago, my high school coach asked if I was going to be back with the Drifters next summer, and he hasn’t been the only one to ask,” Crist says. “I have three years of eligibility left, and I want to spend the rest of it being a Drifter if I’m allowed to. I know I can speak for others, too.”

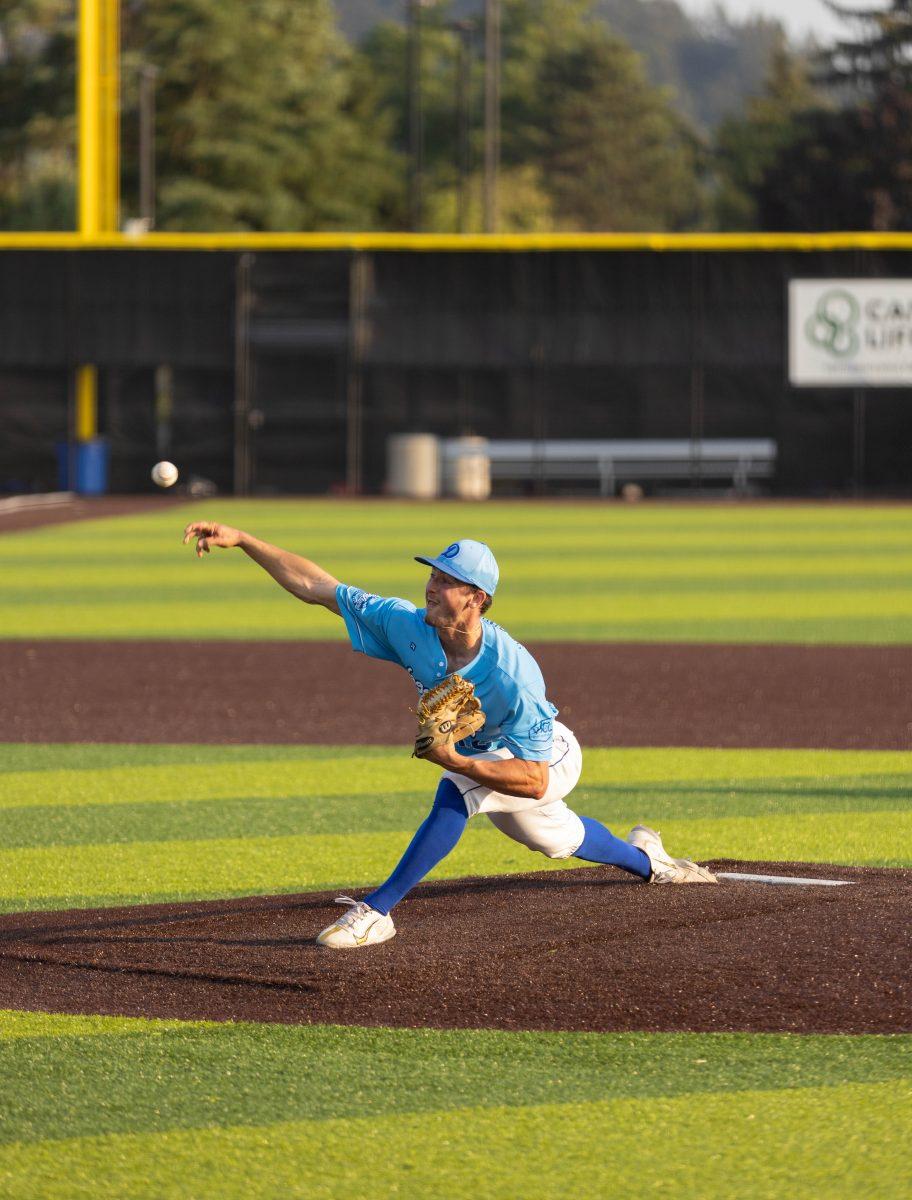

KJ Ruffo delivers a fastball to the plate at the Drifters’ home game versus the Corvallis Knights on July 27. Ruffo will be a junior at the University of Portland this fall.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)