Roger Jensen loaded his electric bike with hand warmers, fresh socks, flashlights, and hand sanitizer. He strapped a hot tin of shepherd’s pie to the bed of his bike trailer. Content with everything secured, Jensen shoved off into the cool February morning.

His first stop was just down the road, a group of four tents connected by footpaths on a grassy field. Jensen parked his bike close to the pavement and retrieved a case of hand sanitizer from his bike trailer. He set it down at the edge of the closest footpath as one of the tents nearest him began to stir.

“Yo, Bent Spoke,” Jensen said to the cluster of tents. “We’ve got food for you here.”

Jensen took the lid off of the tin in his bike trailer and began scooping hot shepherd’s pie into a disposable bowl. A man stepped out of the tent onto the footpath. He introduced himself as Raul.

“One for my girlfriend too,” Raul said.

Jensen handed him his bowl and started dishing up a second. Raul promised to distribute the bottles of hand sanitizer as soon as the others returned to their tents. He took the bowl and waved to Jensen before walking back to his tent.

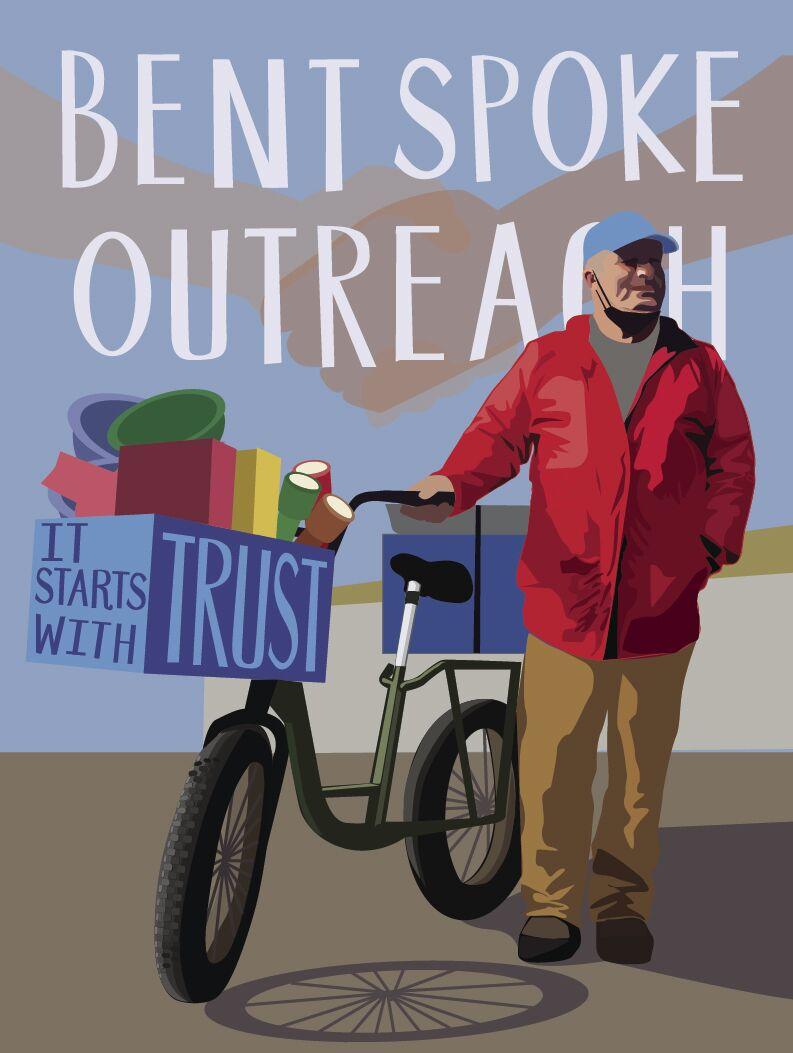

This was the first of more than a dozen stops Jensen would make on this ride today. As Bent Spoke Outreach, Jensen delivers hot food, water, survival gear, sanitation items and fresh clothing to unhoused individuals living in the outskirts of Eugene. Jensen delivers by e-bike and trailer, which allows him to deliver to people who would otherwise be inaccessible by car or van.

Lane County’s homeless-by-name list identified 3,136 homeless individuals living in Eugene in January 2022. Most of the unhoused population in Eugene live on the streets and parks closer to the city center, and Eugene outreach groups tend to focus on distributing food and aid directly to those more densely populated locations. Outreach groups like the Way Home and Free People!, for example, provide food pantry services to the densely populated Washington Jefferson Park.

Unhoused people who have been displaced from large encampments like 13th and Chambers, or who choose to live away from settlements like Washington Jefferson, have a harder time coming in contact with food distribution and aid services.

Jensen began operating Bent Spoke Outreach in January 2021 when he realized that many of the unhoused in West Eugene were unable to take advantage of the aid offered in the inner city. He started out making food to deliver on his own, and he didn’t always have the support he needed.

“I was making a couple hundred peanut butter and honey sandwiches for each ride,” Jensen said.

With Jensen making deliveries up to three times a day, six to seven days a week, it quickly became apparent that he couldn’t do everything himself. He started accepting food and supply donations from individual donors and set up an Amazon wishlist to outsource survival gear expenses.

Over time, Jensen accrued a network of agencies and individuals who support him in what he does. The Way Home and Burrito Brigade, among others, are agencies who already extend their services to unhoused people of Eugene. According to Jensen, Bent Spoke Outreach serves as a conduit for food ministries, like the Way Home, to reach individuals who live away from the city center.

Jensen kept riding on the Fern Ridge Trail towards West 11th Avenue to a small cluster of tents and a trailer at the north end of the Richardson Bridge. There he met up with Tyler, who’d been living here in his trailer for about a month after moving around from different locations in West Eugene for about six months.

Jensen and Tyler chatted for a few minutes as Jensen handed Tyler a couple of hand warmers and a bowl of shepherd’s pie. A friend of Tyler’s had taken some of his tools and refused to give them back for some time, Tyler said. Only recently did his friend make amends and return the tools.

“It’s been a rough week for friendships and personal relationships,” Jensen said.

“Out here’s like that in general,” Tyler said. “It is harsher in the winter, though.”

Some unhoused people in West Eugene live in locations completely inaccessible by car, secluded and difficult to find on foot. Even when Jensen can access even the more remote encampments, keeping track of all the unhoused people in his network can be a real challenge. Many don’t have a reliable cell phone or computer, so Jensen works to meet with people in person. He checks in with most of his regulars three to four times a week, but sometimes people just disappear. When this happens, Jensen will check jails and hospitals, but if they aren’t in either of those places, he has few options for tracking them down.

“I don’t know if they’ve found a couch to sleep on or if they’ve passed away,” Jensen said.

Because contact with the unsheltered people in his network can be tenuous, Jensen relies on word-of-mouth to keep track of many of his contacts. Jensen describes some of his contacts as “peer leaders,” which are people who take on more responsibility within their encampments and who other unhoused individuals gravitate towards for help or security.

Coordinating with peer leaders helps Jensen account for as many people’s needs as possible. Jensen will meet an average of 140 to 180 people during each outreach ride, and he can’t afford to spend too much time with each individual. Instead of going door to door, checking in each tent, Jensen can rely on peer leaders to distribute food and survival gear and disseminate information.

Terry Sampson, who’s been living unhoused in Eugene for 15 years, is one of those peer leaders. On this ride, Jensen was having trouble tracking him down.

“You know Terry?” Jensen asked Tyler as he refastened the lid to the shepherd’s pie.

“Yeah, is he all right?” Tyler said.

“Yeah, they made him move last night,” Jensen said. “The police gave him a 24-hour notice.”

“Tell him to swing by my place,” Tyler said.

Near mid-day, Jensen found Sampson with some friends off of Seneca Road, a few blocks away from where he’d been the night before.

Sampson met Jensen early in the formation of Bent Spoke Outreach and gradually turned into a valuable part of Jensen’s West Eugene network. When the two met for the first time in February 2021, Sampson had brusquely turned him away.

“He told me to fuck off,” Jensen said. “I said, ‘okay, but I’ll be back.’”

Jensen did come back, and over the next few months, Sampson warmed up to Jensen’s aid. Jensen said he considers Sampson a peer leader — other people living on the street trust and look up to him.

Right now, Sampson said, he prefers living away from the city center. He’s wary of living too close to inner-city sites, like Washington Jefferson Park, where frequent site clearance and drug usage make for an unstable standard of living.

When asked if he’d opt for living in a Safe Sleep site if he had the opportunity, Sampson said he didn’t trust them and that he would still be concerned about having his belongings stolen.

“That’s why I don’t sleep at the warming shelters,” Sampson said. “I don’t trust them.”

Sampson’s concerns about theft are not unfounded. For many unhoused individuals, everything they own is in and around their tent. Leaving their belongings unattended for any amount of time might result in important or personal items being stolen. Fear of theft and hoarding are survival instincts for many unhoused individuals, said Jensen.

Jensen plated up some shepherd’s pie for Sampson and his friends. Sampson’s bicycle and bike trailer were parked across the street. Sustained wear and tear made the bike unrideable. If he wanted to move from one location to another, Sampson would need to stand and push the bike, laden with all of his belongings, to the new location.

Sleeping outside on public or private property in Eugene for any amount of time is also risky. Some Eugene city ordinances permit certain types of public camping, but section 4.815 of the city’s municipal code gives the Eugene Police Department the ability to enforce public camping restrictions, and can force unhoused people like Sampson to move. The code defines prohibited public camping as “any place where any bedding, sleeping bag, or other material used for bedding purposes, or any stove or fire is placed, established or maintained for the purpose of maintaining a temporary place to live.”

Sampson, who sometimes sleeps on a tarp with a rain cover, says these restrictions are inhumane, especially given the winter climate in Eugene.

“Camping is something you do on the weekends,” Sampson said. “I am surviving, I am living, but I’m not fucking camping.”

Jensen said he has posted up with a camping chair outside of someone’s tent, given them a bus pass and waited for them as they traveled into town to fulfill aid appointments. This brief guarantee of security is something not often afforded to the unhoused.

By mid-afternoon, Jensen’s tin of shepherd’s pie was just about depleted, but he needed to make one last stop before he ended his ride for the day. He exited the Amazon Creek bike path and pulled into the parking lot of HIV Alliance.

Along with providing syringe exchange and HIV testing services, HIV Alliance also supplies Naloxone to syringe exchange clients, first responders and the general public. Naloxone, sometimes more commonly known as the nasal spray Narcan, is an opioid antagonist that, when administered during an opioid overdose, can restore normal breathing to the patient. Bent Spoke Outreach is not a healthcare or addiction service, but having Narcan handy helps minimize harm until Emergency Medical Services arrives to provide more comprehensive care.

As HIV Alliance staff prepared Narcan kits for Jensen, he sat down at the adjacent booth for a quick COVID-19 test. Jensen would be going on his first vacation in a year, he said, and he wanted to make sure he tested negative before traveling. Jensen would be in Spokane, Washington, for the next 10 days in, spending time with loved ones and considering starting a Bent Spoke Outreach branch there.

Between mutual aid, the unhoused population and the city government, Spokane seems more disconnected than Eugene is currently, Jensen says. Spokane’s 2020 point-in-time count reported that 35% of the city’s 1559 homeless individuals were living unsheltered, a 10% increase from the year before.

Jensen says he doesn’t plan on leaving the Eugene area until he knows that Bent Spoke will run smoothly without him. Jensen is Bent Spoke Outreach’s only consistent rider since its inception, and his role as West Eugene’s only outreach-by-bicycle service is not easily filled or replaced.

His tin empty, Jensen took the loop trail west past the Amazon Corridor. He parked his bike in the warehouse in front of Everyone Village, one of Eugene’s Safe Sleep sites. Jensen has been living on-site at Everyone Village since December 2021. The warehouse at the front of the property serves as Bent Spoke’s base of operations, where Jensen can store survival gear for future rides and maintenance his e-bike.

When Everyone Village opened for new residents in late 2021, Jensen helped 27 people relocate off the streets and into transitional or semi-permanent housing. In January alone, Jensen helped relocate 18 people.

“For a lot of residents, having a lock on the door is a first,” Jensen said.

Jensen remembers an individual he’d helped move from the streets to Everyone Village. Jensen knew he was a peer leader in his community. When he found out that that individual had been living in a tent for 27 years, Jensen encouraged him to apply to live at Everyone Village. Thanks to Jensen’s recommendation, the individual was soon moved in and adjusting to life indoors.

Pastor Gabe Piechowicz, a key leader at Everyone Village, handed him the keys to a tiny home. Later that night, that individual came up to Jensen’s conestoga and asked him, “Should I leave the porch light on at night or shut it off?”

“That’s your home,” Jensen replied. “You get to make those decisions.” Jensen had known this individual for 11 months, and he had never seen him smile before that moment.

As of February 2022, about 200 of Lane County’s 4000 unhoused people live in a programmatic alternative shelter project. As each project site develops, vacancies will open up, but no one site can offer a panacea housing solution. Not every unhoused person in Eugene will have the opportunity to move into a Safe Sleep site this year, and not everyone will want to.

Whether they’re living in a house, an RV or a tent, Bent Spoke Outreach tries to establish relationships and build trust with as many people in the unhoused community as it can.

Jensen unlocked the door to his conestoga, a soft-roof single-room shelter. Today’s ride was shorter than most, and Jensen had dozens more people to check up on before his trip to Spokane. He decides to rest up before reloading his bike and doing the whole thing over again that evening.

Terry, an unhoused individual living in Eugene, picks up food from Bent Spoke Outreach. Terry says that being unhoused is not comparable to camping. According to Terry, camping connotes leisure, while his life is characterized by survival.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)