The tapping of children’s feet and the weeping of a grieving woman echoed against the gray, looming walls of La Cabaña prison as nine-year-old Ruben Lara ran around the courtyard. Patches of moss clung to the stones — the only sign of life in a place defined by death. Paying no mind to the trembling hands of his mother comforting his sobbing aunt, Ruben and his cousins continued to play.

Engrossed in his game, Ruben didn’t notice the open courtyard turn into a dark, secluded hallway as he turned a corner. On the far wall, unseen to him, remnants of old gunpowder and dried blood left a silent mark of what had happened there. He stopped to catch his breath, laughing softly at his clever escape until a hushed voice from the shadows cut through his amusement.

“Do not laugh. There is no joy here; this is where people go to die.”

Now, at the age of 74, Ruben can still remember the soulless eyes staring down at him.

Ruben Lara fled the Cuban regime over 40 years ago, but his past never left him. The death of a childhood, the horrors of forced military service, and the desperation to escape still shape his every decision to this day.

Miami’s Cuban culture thrives in Spanglish street signs and festivals bursting with music and island pride. But beneath this vivaciousness lingers something else — something Ruben knows all too well: fear.

When Fidel Castro seized power in 1959, he promised prosperity. Many Cubans, desperate for change, embraced his vision. “Not everybody that joined Castro was bad,” Ruben said, “It was a change that the Cubans wanted because they knew they could be better.”

However, that promise was never fulfilled as Castro deviated from his original ideology.

“Castro and his collaborators took the revolution in a direction that was not the initial project. That direction upset a lot of people that didn’t like that,” University of Oregon history professor Carlos Aguirre said. “About 600,000 left … in the matter of five to six years.”

This reign of broken promises has left a lasting scar on the Cuban community. In the United States, many have shaped their political choices around one goal: ensuring Cuba’s fate is never repeated. For decades, this fear aligned them with the Republican Party’s staunch anti-communist stance.

But as the Trump administration vows to take away choices, some Cubans are reminded of their time in a one-party, one-way world.

The Lara family and friends gather to celebrate Ruben’s birthday

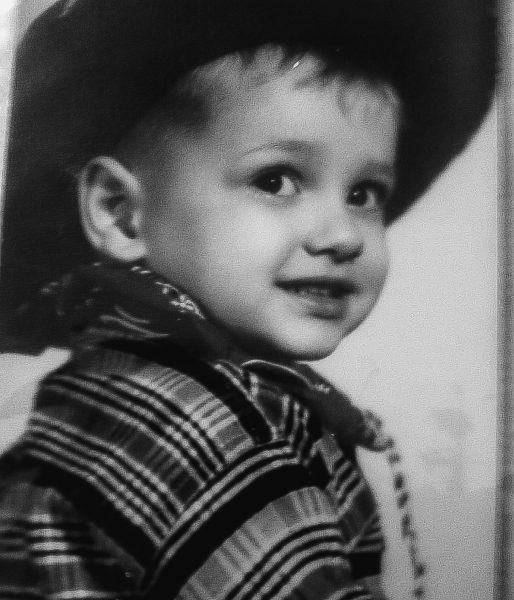

Born in Havana, Cuba on Jan. 1, 1951, Ruben has seen every side of the story. Fulgencio Batista was the “president” of Cuba during Ruben’s childhood, though, according to Aguirre, he was considered “a violation of the constitutional democratic process.” Batista mainly focused on Cuba’s economic success but let social injustice languish throughout the country. Despite this, Ruben recalls having a happy childhood.

“We weren’t rich, but we had a good life,” Ruben recalled, his voice tinged with nostalgia. His childhood was filled with laughter — family get-togethers that lasted until dawn, road trips through Viñales Valley and Cueva de Bellamar, and afternoons spent teaching tricks to his beloved goat, Katrina.

Like most kids, Ruben had a mischievous side. “Oh, he was so mad when he heard I was coming along,” his sister, Mayra Lara, said. “He threatened to pack all his things and leave the house. I think he actually pulled out his suitcase.”

However, this rebellious streak soon ended after Mayra was born. “Ruben was such a caring brother. He would rush home before all his friends would come over so he could tell our mother and I to get ready. He wanted his friends to think he had a pretty family,” Mayra said.

This optimistic perspective was a trait he had developed at a young age. “He was so calm, cool and collected, even as a child,” Mayra said. “My mom would tell him off, and after she was done, he would go and make sure to give her a kiss because that’s who he was. He never wanted to hold that anger.”

But childhood didn’t last forever, and in Cuba, neither did peace.

Batista fled the country in the early morning of Jan. 1st, 1959, allowing Castro’s forces to enter Havana to take control. “I had always been against Castro. I realized the first day that it was bad,” Ruben said.

During Castro’s Revolution, Ruben’s father, an official in Batista’s army, was captured. For eight days, he was held captive in a theater until Fidel Castro officially arrived in Havana.

A young Ruben models his cowboy attire

“I didn’t know if my dad was alive. There was no communication, so we had to think about that,” Ruben said. “I knew then that nothing would be the same, and it wasn’t.”

Castro’s promises of universal healthcare, social justice and equality attracted widespread support across the island. But as time passed, those who had once believed in the idealistic vision faced a harsh reality: unfulfilled promises, escalating repression and a government that betrayed the very people it vowed to protect.

“There were policies and measures and decisions that indicated an increasingly more authoritarian type of regime,” Aguirre said.

A year into his reign, Castro’s true ideological stance became clear. His adoption of communism undermined the democratic hopes many had placed in him.

“Everything was rationed— food, clothes, toys — I mean everything. We had a ration book that we’d take to the market to get everything for the month, but even then, you didn’t have a lot to choose from,” Ruben said, “It was so difficult to get toys that we got a dog so that mainly my younger brother could have something to play with. I wore the same pair of shoes for everything, especially walking to school. I would duct tape and fill them with cardboard because I didn’t have another pair.”

The influence of the Revolution stretched beyond scarcity; it reached into the classroom. Schools became centers of political indoctrination. “We had to repeat phrases like ‘capitalism is bad’ and anything that supported the Revolution,” Ruben said. “They made it seem like Cuban history had led to this point, you know, figures like José Martí would support the Revolution’s ideas.”

But for Ruben, no amount of classroom rhetoric could erase the truth he had seen with his own eyes. “I had a teacher say that the prisons weren’t bad and it was propaganda, but I told her no, I had seen it myself. I visited family members, and no matter what my cousin or I said, she wouldn’t believe a word,” he said.

The community Ruben and many other Cubans had felt in their neighborhoods disappeared as people left the country, and a once-trusting community turned into vigilance committees watching every move.

“Neighbors who you had known and they knew you … you couldn’t act the same,” he said.

People who strolled along the streets, stopping to chat with one another, now acted as informants for the Revolution.

“It was a mentality of ‘you were either with me or against me,’ no middle ground,” Aguirre said.

These groups had one clear purpose: watch, report, punish. It wasn’t long before Ruben’s family became a target.

“At first, we were questioned because my dad was in Batista’s military,” Ruben said. Then came the raids. Car engines roared down the street, followed by the quiet, dreaded knocks. Armed Revolution troops escorted young Ruben and his family outside to watch them ravage the home as neighbors watched. “It was people we had known for years that did that, and they dared to watch it happen.”

The raids happened two more times that month. And each time, there was nothing Ruben could do but stay silent. “I had never held more anger than when I had to hold my tongue in the face of everything. There was nothing I could do.”

Ruben couldn’t even escape the tensions in the solace of his own home. The framed pictures of past gatherings mocked the quiet that had settled over the Lara household.

“We tried to still get together, though it was rare, but everyone was on edge and mainly kept to themselves. When people would leave and say they had fun, it was sad because we all knew it wasn’t the same,” Mayra said.

The warmth of family gatherings had faded, replaced by quiet caution. Even in their own homes, Cubans lived with the unspoken understanding that too much laughter, too many visitors or the wrong conversation could draw unwanted attention.

But beyond the walls of their home, the consequences of dissent were even harsher. Under Castro’s rule, imprisonment became one of the regime’s most feared weapons. The Organization of American States’ Commission on Human Rights reports that one out of every 94 Cubans were behind bars in the 1960s.

That equals 77,313 people in jail during the first few years of the Revolution.

“If you got caught doing anything against the Revolution, you knew you were going to jail, no matter how small it was,” Ruben said. “Someone I knew had thrown a pocket knife at a poster of Che Guevara, and at trial, he was sentenced to 18 months.”

But trials were a mere formality. “You’re convicted before you even step into the room. Lawyers will tell you to just accept it; they wouldn’t even try arguing your case,” Ruben said.

The Revolution had reshaped everything — even childhood. Family trips once spent cruising down the Carretera Central — Cuba’s main highway — were now spent visiting relatives in prison.

At the start of the Revolution, Ruben already had seven family members in jail, three of whom were sent to some of the more animalistic prisons. “We tried to see everyone as much as we could, but most of us were kids. We couldn’t go where some of them were. They were plantados and plantadas — hard cases or difficult prisoners in English — so they were in the crueler [prisons]. You couldn’t see the actual cells or the whole prison, but you could tell it was bad just by looking at [the prisoners]. My cousin was 18 when he went in … he looked as though he had lived four lifetimes by the time he was out,” he said.

Though most of his life had changed, Ruben found small ways to rebel.

During the 1960s, The Beatles defined a generation — everywhere except Cuba. Castro had banned American media, calling it imperialist propaganda.

Simply humming to the joyous sounds of John Lennon could get you beaten or land you in prison. “If you had any long hair, you know, like the ‘Abbey Road’ album, they would come up to you in the streets and just chop your hair,” Ruben said.

Still, Ruben and his friends would huddle around a low-quality metal disk to listen, enjoying having something away from the government. His favorite song? The Beatles’ “Do You Want to Know a Secret.”

Even though he had every reason to, Ruben didn’t let the Revolution take away his kindness.

“Even after everything, he was still my caring brother,” his sister said. As he grew, Ruben was known to raid pantries, searching for anything that could sustain his immense appetite. “He would go after everything in seconds, not a crumb left. He was like a vacuum,” Mayra said. “But he never tried to touch my food. I was picky, which wasn’t great since everything was already limited, and the only thing I really enjoyed was sweetened condensed milk. No matter how hungry he was or how long the can sat in our kitchen, he refused to eat it.”

But his greatest act of love was not what he refused to take — it was what he gave.

“I have to thank him for being here in this country,” Mayra said.

At 17, Ruben knew he couldn’t leave Cuba. Men aged 15 to 27 were military-aged and forbidden from leaving. But he could make sure his family did.

“He didn’t want us to live through that, so he told our mom to take my brother and me away even though he couldn’t come with us,” Mayra said. Ruben knew he would rather face living in this country alone than subject his siblings to what he had suffered for most of his life.

Ruben wasn’t drafted right away. “I wasn’t called in the first draft of the area, so I was able to pick up a job and live near my aunt,” he said. But staying behind came with its own challenges — he was left alone, except for his brother’s dog.

“I wasn’t close with it; it was my brother’s dog. He barely listened to me. But we were all we really had left here, so I came to really rely on that dog to get me through those times alone.”

As he waited, Ruben took work in the fields, but his affinity for numbers led to a promotion. “I was wondering why I hadn’t been called yet, but when I was promoted, I kind of focused on that. Apparently, they found me really useful because they had been hiding my calls to action for the longest time,” he said.

At 25, Ruben was finally drafted. He trained intensively, rising through the ranks to lead an artillery unit. Most of his service was routine: moving tanks, transporting equipment and following orders.

But everything changed when Cuba entered the Angolan conflict.

By the 1970s, Castro had sent thousands of Cuban soldiers to Angola, backing communist factions in their civil war. For Ruben, it meant fighting for a cause he didn’t believe in.

“I haven’t spoken about my time in the military for 30 years,” he admitted. “There are some things, details that you don’t forget, and that’s one of them.”

Before deployment, he was pulled out of his unit due to his family ties in the United States, which raised suspicion of possible treason. Ruben begged the intelligence officer to let him join his crew, not just to prove himself, but because he refused to let his unit go in without him.

“You know, you train with these people for so long … I just couldn’t not go with them,” Ruben said.

Within days of being deployed, his entire unit had died.

With Cuba doing poorly in the war, Ruben was offered the chance to prove his innocence and was sent with a special unit to Angola. The group trudged along the Angolan landscape for 75 days.

The canopy trees towered over, making the land itself seem mournful. The land around them held remnants of past conflicts; spent shell casings riddled about and bodies so mangled, it was difficult to tell what side they were on.

“There was this constant fear you were being tracked as you moved, and sometimes you were, and you had to react. If you have fear in those moments, you died,” Ruben said.

In conflict, for soldiers, morality is just a concept, and death is almost a certainty. It is only afterward that morality is questioned. “I just couldn’t help but think that they were sons, fathers, people … and I just killed them,” Ruben said. The confrontations lasted no longer than a couple of minutes, but their impact still haunts Ruben to this day. “For the rest of my life, I must live with it.”

Experts estimate that over 500,000 casualties occurred during the Angolan conflict.

Ruben’s journey to the United States was anything but direct. During the 1980s, there was no visa pathway from Cuba to the U.S., so people found other routes. Ruben spent six months in Costa Rica, waiting between the life he had left behind and the one he hoped to begin.

Finally, his mother and sister came for him.

“I hadn’t seen him in years,” Mayra said. “But it was more stressful than emotional at first because we were focused on making sure everything was fine at the embassy. When we finally got to the hotel room, that’s when we all burst into tears and hugs.”

Despite being apart for years, the siblings still shared a sense of playfulness. “I had gotten a can of sweet condensed milk,” she said. “After we finished crying, I looked at him, poured it down the drain, and said, ‘We don’t have to worry about this anymore.’”

At last, Cuba seemed behind him. Ruben moved in with his parents and quickly found work at the American Welding Society in Miami. His skills with numbers helped him secure a finance position. Soon, he had a home, a family, and the kind of stability he had long imagined.

But the past doesn’t disappear just because the scenery changes.

“I didn’t try to raise my sons with this fear of what happened on the island,” Ruben said. “But I couldn’t let it go.”

Miami, for all its Cuban pride, was still a city haunted by exile. Conversations on the street, at school and in the house all revolved around what people had lost, what they had escaped, and what they feared could happen again.

His current wife, Martica Ventura-Lara, remembers how well he hid his past.

“When I was first getting to know him, you wouldn’t have thought anything was wrong. He made it seem like he was cruising in life,” she said.

David Hoodiman, his neighbor of over a decade, recounts his surprise at their shared military experience. “I was still surprised that we shared the brotherhood of being in the military. You don’t really talk about these things, but there was nothing from him that gave off dealing with that. We had been neighbors for about seven years by that time, and it was just something I never knew,” he said.

But Ruben’s fears were still there — just buried under the surface.

Like many who had arrived in the U.S., Ruben’s political stance was not based on party loyalty, but on survival.

“It’s not that we agreed with the Republicans,” he said, “it was that communism was potentially associated with the Democrats. That didn’t make them an option. It couldn’t happen again.”

For years, that fear dictated his choices. Ruben refused to leave Miami, terrified of separating from his family again. He refused even to consider voting for a Democrat, no matter how much he agreed with certain policies.

However, something shifted in 2004 when his first daughter was born.

He questioned the weight of the fear he was carrying for the first time. He picked up his old José Martí books, ones he hadn’t touched in decades, and remembered the philosophies that carried him through the Revolution.

“Happiness and love were needed to create opportunity,” he said. “Not living in fear to maintain it.”

The birth of his second daughter in 2010 pushed him even further toward change. Yet, he still couldn’t fully let go.

Not until November 2016.

The 2016 U.S. presidential election brought a new level of hostility to American politics: aggressive rhetoric, deepening divisions and an eerily familiar political climate. Ruben began to question his long-held political stance.

But then, weeks after the U.S. election was held, Fidel Castro died on Nov. 25, 2016. Miami exploded into celebration. Crowds flooded the streets, singing, dancing, and banging pots and pans.

Ruben felt a mix of emotions: a sense of happiness and a resurgence of old feelings, things he had long thought he had buried. Memories surfaced: the Revolution, the fear, the loss, the silence and the sacrifices.

It all came crashing back.

With all these emotions resurfacing, any questioning Ruben had begun, evaporated as his fear returned. His unwillingness to change ignited a firestorm in the house — between him and his eldest daughter. “I remember it was nonstop between the two of them. For weeks after the election, you would just hear screaming in the garage or the living room,” Martica said.

But in 2020, with two grown daughters, Ruben realized he needed to be mindful of their futures and not just his past.

As the election season unfolded, he was uneasy, shifting in his seat as he flipped through channels. “The way some of these people were talking … I just couldn’t look my daughters in the eyes, knowing I blindly followed that because I was scared.”

For decades, fear had dictated his choices. But one night, after yet another political argument with his eldest daughter, something cracked.

“I’m just scared of [communism], a word that has meaning, but it’s just a word,” he admitted to Martica. “I’m their father, and I can’t let a word get between me and ensuring they have the life I never did.”

It was the first time he had ever said it out loud.

For the sake of his daughters, Ruben voted Democratic across the ticket for the first time in the 2020 election.

“I hear what they say and see what they’re doing … I’m just reminded of Castro. Everyone deserves to have a choice … I don’t care if it means I have to vote blue; I will always vote for my daughters’ choice.”

Now, Ruben focuses on the little things. At lunch, he calls his sister to see how things are on the Gulf Coast. He drives to his mom’s apartment, sipping cafê while updating her on her granddaughters.

“You know, I think I should put her in MMA with how aggressively she hits,” he jokes, shaking his head at his youngest daughter’s volleyball skills.

Later, he stretches out on the couch, letting the soft hum of his Turkish drama fill the quiet. His phone is off vibrate — he knows his eldest daughter will call, forgetting the time difference, as always.

In the summers, he drives down State Road 84 with The Beatles on loop. “Do You Want to Know a Secret” plays as he takes his daughters to volleyball, joking about his goat for the 50th time as if it’s the only thing he remembers from his childhood.

But it’s not.

He remembers the sunburns pulsating on his back as he worked in the fields, the occasional breeze being his only relief.

He remembers how his mom smelled before she left for the States, holding him for 20 minutes.

He remembers the lives he cut short, their faces draining of color, their bodies crumpling to the ground.

He remembers everything.

It’s the reason he logs onto Zoom on sunny Sunday afternoons. Familiar names appear — old friends from Cuba, rediscovered after decades of silence. It’s sunny there too. The screen flickers with faces he barely recognizes, aged by time, but voices that still carry the pain as they recount simpler times. The trauma still latches onto their shoulders, carrying it around with every step, but Ruben refuses to hear that pain in his daughters’ voices.

“If you had asked me five years prior if I would’ve [voted entirely blue], absolutely not. I still remember the pain, the isolation, the death, everything back in Cuba,” Ruben said. “But my daughters come first. I may not agree with everything, but I have so much faith in you girls and what you’d do with a choice.”

As he sits in these interviews, his hands shake. When footsteps pass, his eyes flicker toward the door, and his voice lowers when he hears movement outside.

But he never stops.

He’s never told this story, but for me, he would.

As his daughter, the least I can do is recognize his attempts to change, even if I don’t always agree with him. He has told me more than enough stories to fill a book; now, it is my turn to tell stories. And I will start with this one.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)