It’s Saturday night in Havana, Cuba. I’m standing with an American friend outside the Karl Marx Theatre trying to find illegally scalped tickets to a sold-out stand-up comedy show.

Our guide, Alberto González Rivero, a man who has directly interpreted for Fidel Castro, wanders through the stylish crowd looking for dealers. Our cab driver patiently waits in his 1928 pink Ford convertible just in case we can’t get in. A young guy approaches us and offers to sell us a ticket. “Alberto!” I call out. Our guide walks over. The scalper sees we are with another Cuban and disappears.

Nearing show time, we finally find a more trustworthy group across the street. They bump the price up: three CUCs, or Cuban Convertible Pesos, for each of the three tickets, which is still only about $3.35 U.S. per from the original $0.80. We’re happy to pay it. Even in the socialist country, the cheap prices surprise us. Alberto had mentioned that the headliner, Kike Quiñones, is one of the most famous comedians in Cuba.

Inside the theater, which was formerly named Teatro Blanquita before the 1959 revolution, we find a packed house, almost filled to its 5,500-seat capacity. Young, old, intellectuals, working class, families, students, and even political leaders are known to fill these rows. People are out and eager to laugh. Ready to whisper English translations, Alberto sits between my friend, Reuben, and me. On the stage, we see the name of the show, “Recordar es Volver a Fingir,” which is, roughly: “To Remember is to Pretend Again.” The lights go down and the show begins.

I didn’t know what to expect.

“Comedians are the ones that are the boldest about every single problem we have,” Alberto tells us. “They criticize very boldly. So, that’s why people laugh so hard.” The night and its audience unwind. Quiñones, along with two other comedians, Carlos Gonzalvo and Luis Silva, take the stage in a frenzy of jokes.

“Cubans know ahead of time that there is nothing in the refrigerator,” says Quiñones, pretending to rummage. “We just open it for fun.”

Quiñones begins to break out in song, singing of the bumpy streets, shanty-towns, and illegal migrants from other provinces. Gonzalvo, dressed in disguise, pops up from within the audience, “Twenty cents is too much! You’re ripping these people off!” They banter, much like a late night host and his sideman would, and the crowd plays along. Now, the stage is set for a skit. Out comes Silva, cross-dressed as a Chinese cooking show hostess. Reuben and I give each other a look, the holy-shit-this-wouldn’t-fly-in-America kind of look. Quiñones walks out in a dress, Silva’s Cuban cooking counterpart.

In Cuba, Chinese cooking shows are popular due to the healthy political and cultural exchange between the two countries. The skit mocks how ingredients needed for Chinese recipes aren’t available in Cuba. It ends with the hostesses exchanging gifts: television show files from their respective countries. The Chinese woman gifts a hard drive and the Cuban gives a cassette, “Be careful, the tape can get stuck, just like Cuba.”

Out comes Gonzalvo, alone.

“Cubans have been trained for years to live through an international crisis,” he says. “In New York, there was a blackout for 10 minutes and 40 people committed suicide.” His raspy voice and matter-of-fact tone adds spice to his jabs, “In Spain, when people want to protest, they make signs with cardboard paper. In Cuba, we don’t even have cardboard paper.”

Then, Silva saunters out into the spotlight for a solo stand-up set. This time, dressed as an old man. Among all kinds of things, he speaks about the improving Cuban-American relations. “Next year, people will be hitchhiking on boats to get to Miami!”

He waddles back and forth across the stage; people don’t have time to catch their breath. He pokes fun at the quality of Cuban food: “Customs in America is difficult,” he says. “The border agent took my bread back for testing. He returned: ‘Well, it’s not a bomb and it’s not drugs, but don’t lie to me and tell me this is bread.’”After two hours, the three comedians get on stage and take their bows. I look around at the faces in the crowd. It’s dark. People are smiling. I wonder where home is for each of them.

After the show, I speak to Mildred Rodriguez, a Cuban-born woman who had been sitting behind us. In 1997, she moved to Lakeland, Florida. During her annual trips to visit family, she has noticed some changes: “See, Cubans, with their problems, anything, they always try to make something fun out of it,” she says. “Before, you couldn’t say anything but now, for some reason, things have changed.” The show seemed to happen so quickly and there was so much going on that it felt like sensory overload at the time. There was a lot to take in.

As an American, I had come eager to hear Cubans’ perspectives about their government. It was surprising to hear the honesty in the jokes, even more so after I learned Quiñones is the director for the Center of Humor Promotion, which is a department of the State. But for all of the economic and political criticisms, their acts were filled with universal themes. Had the Karl Marx Theater been ripped out from its foundation, placed somewhere in America, and translated into English, it would have just been a regular comedy show. I don’t know if I would have noticed the mix of political and observational jokes, and there were some observational jokes: They talked about the gossiping old women in their neighborhoods; how flight attendants remind nervous people of everything that could go wrong during a flight; the strange sensation of turning 40. They reveled in the luxury of a good fart while watching television and laughed at a grown man’s giggle when the cold ocean water reaches his crotch.

I found out a lot by going to the show, but it also may have reconfirmed things I already knew. These comedians were shedding light on certain truths; that’s the job of a comedian, especially a stand-up. People were delighted, surprised, and shocked to hear reflections of their own private thoughts belted out on stage by another person. That’s part of why comedy bonds people so tightly.

In Havana, it’s another world, but it’s filled with people, just people. And it felt good to share a laugh with them.

Michael McGovern, a University of Oregon alumnus, traveled to Cuba in 2015.

McGovern: Comedy at the Karl Marx Theater

Michael McGovern

February 17, 2016

Andy Abeyta

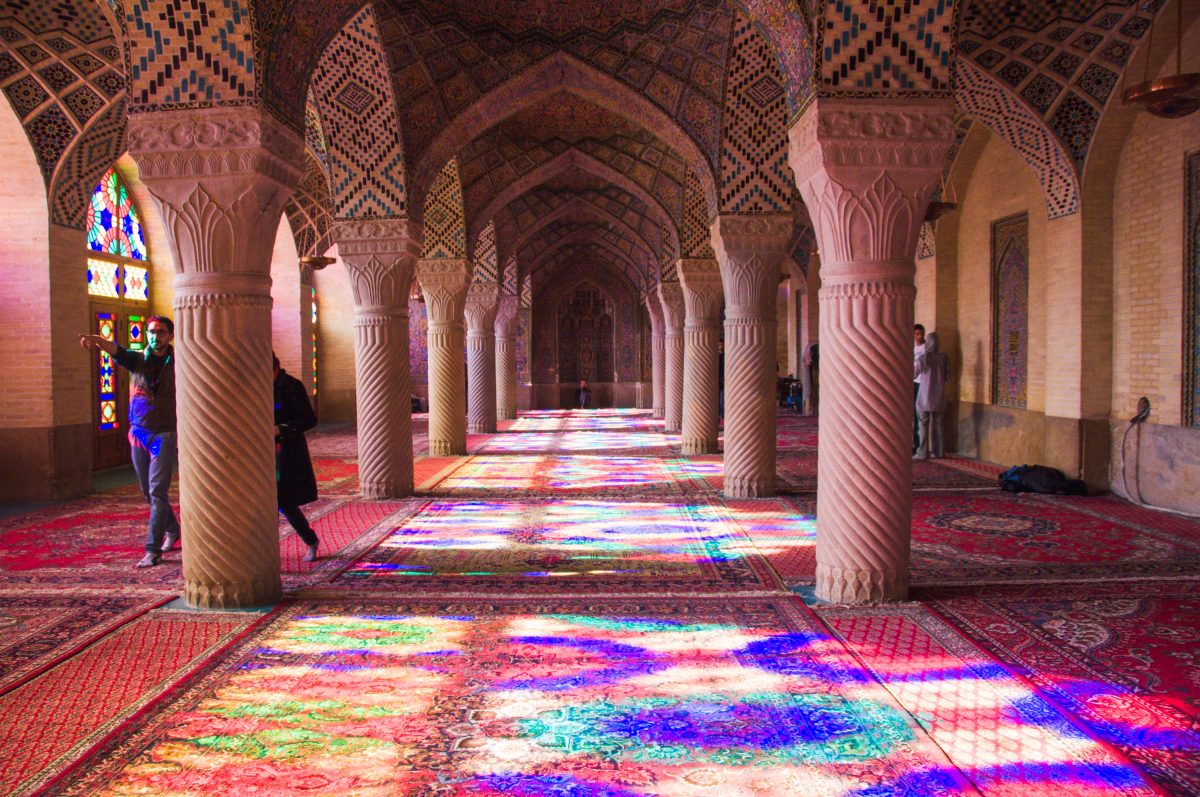

(Photo courtesy of Andy Abeyta) In the distance, tourists walk among streets mingling with locals enjoying a night out as well as vendors and other workers that inhabit the streets of Old Habana as seen on Sunday, March 22, 2015. The old district of Habana displays a wide variety of forms of architecture reflecting upon the varying influences from around the world that compound and expand the culture of the central Cuban city.

0

Donate to Ethos

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Oregon - Ethos. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover