Words and Photos by Dahlia Bazzaz

I became a woman in the arrivals section of London Heathrow Airport.

Not long after my mother and I departed our plane, she reached deep into the front pocket of her overstuffed carry-on. When her hand emerged, it held a square, cerulean hijab.

She connected the corners into a triangle, knelt down in front of me, and placed it over my head. As she fastened a pink, butterfly-shaped clip under my chin to connect the two halves of the scarf together, I watched her eyes dart in every direction except mine.

It was a last-minute effort to make me decent before my Persian-Iraqi mother’s conservative Muslim family members arrived to pick us up from the airport. At nine years and two months, I was already past my Islamic deadline for modesty.

The hijab and I remained together for nearly a decade after our first, abrupt introduction in the summer of 2003. To my mother and her extended family, the hijab represented a piece in the jigsaw puzzle of femininity. A puzzle that — to me — couldn’t be solved.

So on the first day of my sophomore year at the University of Oregon, I traded in my headscarf for a hair straightener. I straddled two different versions of myself for the next eight months, until my mom found a photo of me on Google images. It was a week after my 20th birthday, in late May 2014.

Living with my father and brother in our suburban Portland home, she ignored my calls and texts for days. My brother told me that my mother looked like she was mourning a death. After a week, she showed up at my apartment in Eugene looking for answers.

“You broke my heart,” she told me between heaving sobs as she sat on the edge of my bed. She buried her pale face, framed by a navy headscarf, in a worn tissue. Everything else she wore was black. Her purse and jacket stayed on her shoulders for the entire two hours she spent at my apartment. I watched her writhe and bend with her cries from across the room.

Much of my mother’s pain healed with time. But to say I’ve been hijab-free for the last two years would be a lie. It comes back into my life every so often: sometimes in trips to the Shia mosque in Portland during Ramadan, sometimes when old family friends come over for dinner.

During those few covered hours, my mom might look at me with a weak smile resting on her high cheekbones. “You look beautiful. Inshallah (God willing), one day …” she trails off.

Watching her try to reconcile who I’d become with her seemingly rigid boundaries of morality grew exhausting. Friends pitied me. I pitied me. Whenever I described the relationship between my conservative, immigrant mother and me, I’d get the song “Reflection” from Mulan stuck in my head.

Look at me / I would never pass for a perfect bride / or a perfect daughter … So it seems / that if I were truly to be myself / I would break my family’s heart.

My perceptions of my mother carried rigid boundaries of their own, too. I carried the weight of our conflicts to every interaction we had. I’d bail for family dinners, fearing a hijab talk after them. Our phone calls dwindled to under three minutes a piece.

But those boundaries began to flex last winter, when I took a three-week trip to Iran and the United Arab Emirates with her to visit family. I initially resisted the idea — to keep up appearances, I’d need to wear a headscarf the entire time — but in the face of my apparent reluctance, my mom had resorted to sending me slideshows of my aging grandparents in Iran, set to melancholic music.

For most of my life, I’ve been my mother’s travel companion. Whether it was a 15-minute trip to Costco or a five-week trip to Hajj, we’d clocked thousands of hours in transportation together.

Sometimes, in an effort to sweeten the trip, she’d go out of her way to make things easier: Once, she even lined the shopping cart with towels from the home department so I could nap while she shopped. Another time, she revealed three coloring books and a 64-pack of Crayola crayons half-way into a transatlantic flight.

But as I soon found out, this trip would be a little different.

During the 14-hour flight from Seattle to Dubai, my mom pulled out a baggie filled with Valium from her purse.

“Mom, what the hell?” I said.

“If I don’t take these, I’ll never fall asleep,” she replied. “I know you’re a light sleeper too. Yella, take one of these.”

My mother — a woman who has spent the last 56 years of her life staying away from alcohol and virtually all other substances — was peddling me prescription drugs left over from oral surgery. One seatback version of “The Notebook” and three cases of sleep paralysis later, I awoke to landing turbulence.

While I reached into my backpack to grab my headscarf and a cardigan, my mother retrieved a black abaya from her purse. We were both keeping up appearances for our relatives.

When we walked into 85-degree weather outside of Dubai International Airport, I complained of the heat and tugged at my hijab. My mom ignored me. I look over and see flushed face scanning for my aunt between the cabs. When she finally spotted her, my mom grinned like a child and rushed over to her.

The two sisters embraced, and I realized that even with yearly visits, two continents have separated my mother from her immediate family since 1978 — when my mom left Baghdad at 18 years old so my father could study at the University of Oregon.When we arrived at my grandparents’ house in Tehran 10 days later, my grandfather held my hand and slapped it lightly, chastising me for being immodest by staining it with a henna design.

“If you think that’s strict, you should have seen how I grew up,” my mother said to me, chuckling. In those days, she and her sisters weren’t allowed to attend college, and some married before their 18th birthdays.

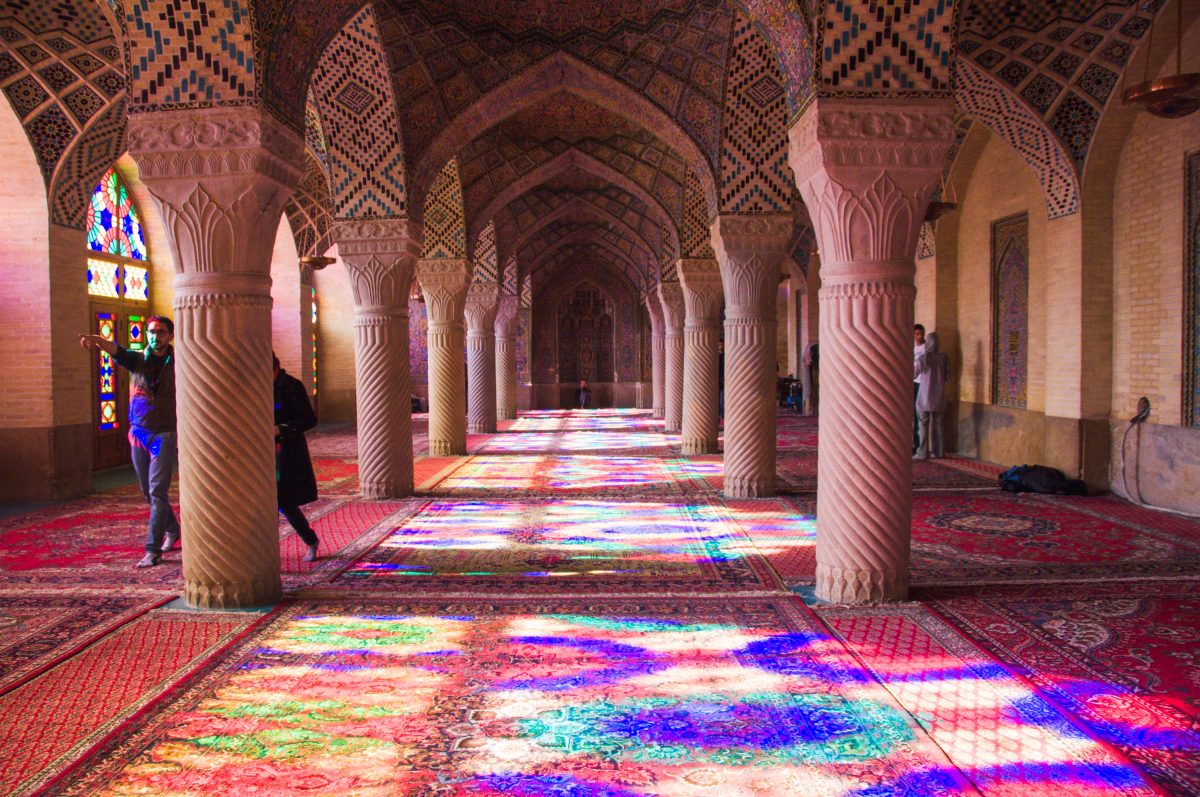

We traveled alone to the city of Shiraz, and I watched her mouth off in broken Farsi when a taxi driver tried to rip us off. I discovered her enthusiasm for ancient ruins during a tour of Persepolis, where she stopped every few feet to take photos and berate our guide with questions.

Before, back at home, I feared my mother’s judgement because of her background. But on that three-week expedition, she was my closest confidant and the only person who knew English. We shared the day’s drama as we lay over bright Persian rugs in our shared room, hearing the call to prayer trickle in slowly from the window. Little by little, I watched the image of my mother change from dogmatic to daring, from my biggest adversary to my biggest ally.

During that trip, I saw beautiful sights: the largest mosque in the world; the intricate turquoise tile lining the tomb of Hafez, my favorite Persian poet; the sun setting deep in the Dubai desert.

But none were as beautiful as the emerging image of my mother — complicated, conflicted, and so much more than the one who knelt before me at Heathrow Airport.

(Dahlia Bazzaz)