Experts question if hormonal injections prevent repeat sex offenses or just distract from the real issues.

Story by Erin Peterson

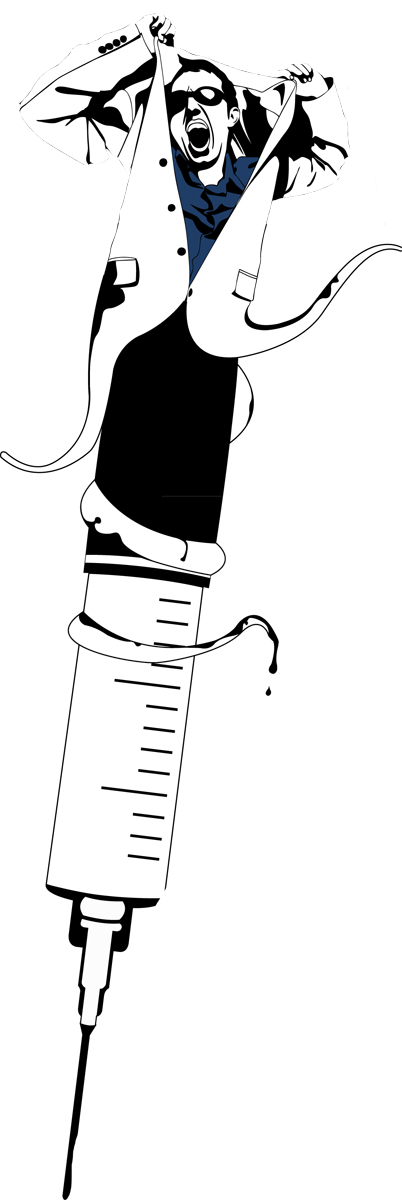

Illustrations by Christopher Fellows

In 1983, Joseph Frank Smith stood in front of a Texas state jury awaiting the court’s verdict. The jury found him guilty of two accounts of rape. Rather than go to prison, he volunteered for a ten-year probation period of chemical castration, a method in which he would be injected with an anti-androgen drug, specifically a female contraceptive that would lower his testosterone levels and significantly reduce his desire for sex.

He was admitted into a program at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, where he was injected with the drug every three months and underwent intensive psychotherapy. One year later, Smith became the poster child for chemical castration and appeared on shows like CBS’s 60 Minutes as a success story for the treatment.

In 1998, Smith stood in front of a jury once again. This time, he pled guilty to two accounts of sexual assault that he committed in 1993. Police believed that he had been connected to a series of seventy-five sex-related crimes since 1987. Smith’s success story appeared to be a lie.

“Sex is not the only motivating factor in sex offenses,” says BB Beltran, co-director of Sexual Assault Support Services (SASS), a nonprofit that works with the victims of assault in Lane County. “It’s about power and control and a sense of entitlement … I’m not sure that chemical castration would mitigate any of those factors.”

The identification of characteristics associated with sex offender recidivism has been an area of significant research over the past twenty years. In its document, Recidivism of Sex Offenders, the Center for Sex Offender Management (CSOM), an organization created by the US Department of Justice, outlines those characteristics associated with repeating sex offenders with evidence drawn from multiple studies. It concludes that a wide range of factors, from the offender’s age at first offense to poor attitude to alcohol or drug use, determines whether an offender will offend again.

“We need to make sure that the treatment actually fits the offender and is applied in a manner that the offender can reply to,” says Dr. William Davis, a psychologist who works directly with sex offenders in Salem, Oregon. “There is not a one-size-fits-all approach.”

In 1999, Oregon became the second state in the US to enact chemical castration of repeating sex offenders. The Board of Parole and Post-Prison Supervision enforces the treatment based upon an evaluation provided by a psychiatrist who contracts with the Department of Corrections, or at the request of the parole officer.

“The treatment may take the edge off, but it doesn’t take away the fantasies, criminal thinking patterns, or power motivations,” Davis says. “Chemical castration doesn’t take into account how complicated sexual assault actually is,” Beltran says. “It would take away their ability to perform sexual acts, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t do other harm.”

The Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA) stresses the importance of coupling the treatment with a therapeutic program.

“An abuser should be involved in concurrent cognitive-behavioral treatment designed to address other aspects of the deviant behavior in addition to forum sexual interests,” says the ATSA Executive Board of Directors in its public policy statement on anti-androgen treatment. “These medications should never be used as a sole method of treatment.”

Regardless of how effective the treatment may be, the American Psychiatric Association has found that injecting a man with anti-androgen drugs can have some serious side effects, including depression, hypoglycemia, penile and testicular pain, and diabetes. The anti-androgen or testosterone blocker used in Depo-Provera also depletes bone mineral density, making it likely that offenders could experience osteoperosis and multiple bone fractures as a result of the treatment.

“Anytime a physician prescribes a medication, one has to look at the risk-benefit ratio: the therapeutic benefits, the side effects, and the risks of not taking the medication,” says Dr. Frederick Berlin, Founder and Director of the Johns Hopkins Sexual Behaviors Consultation Clinic, where he specializes in the evaluation and treatment of patients with sexual disorders. He admits that there are side effects to the treatment, but they are not any more severe than the side effects of several other medications that many physicians routinely prescribe.

However, from a legal standpoint, various issues arise with forcing someone into treatment.

“Because chemical castration is designed to both shackle the mind and painfully cripple the body of sex offenders, it is doubly cruel and should be struck down as a violation of the Eighth Amendment,” says John F. Stinneford, a professor at the Florida University Fredric G. Levin College of Law, in his essay, Incapacitation Through Maiming: Chemical Castration, the Eighth Amendment, and the Denial of Human Dignity.

Stinneford asserts that the vast majority of sex offenders do not have any kind of sexual disorder. They may be bad, dangerous, or antisocial people, but they do not have a sickness; therefore, rendering the mind incapable of experiencing sexual desire is not even medically appropriate.

“Rather, it merely replaces the stone walls and iron bars of a traditional prison with a less expensive and more degrading prison of the mind,” he says.

The Supreme Court identifies four key points in determining whether a punishment is inherently cruel within the meaning of the Eighth Amendment: (1) Whether it violates the dignity of man, (2) Whether it violates evolving standards of decency, (3) Whether it involves the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain, and (4) Whether it involves torture or barbarous methods of punishment, such as burning at the stake or physical castration.

“There are so many negative medical side effects that requiring someone to do androgen therapy seems like a potential legal problem down the road,” Davis says. “You’re essentially putting a person into a place where they could have serious physical consequences.”

Berlin does not like the term “chemical castration” because it has connotations that can give people reason to hesitate and fear going under the procedure. Some have the wrong impression of what the word “castration” really means. In reality, androgen therapy is simply a medication that lowers the intensity of sexual drive. If a man is hungering sexually for children, reducing that hunger allows him to control himself and resist those temptations more easily.

“There is a tremendous amount of evidence showing that when these methods are used, the sexual recidivism rate becomes impressively low,” he says.

In the case of Smith, Berlin explains a part of the story that was excluded by the media. Smith left the clinic in Maryland for a different medical institution in Virginia in the mid-1980s, where he was taken off the medication and put into behavioral therapy instead, which proved to be a very serious mistake. His recidivism occurred when his anti-androgen treatment was discontinued.

But Davis argues that therapy back in the 1980s was not really therapy. “I can’t tell you how aggressive and brutal it was,” he says. “It was a little less like therapy and a little more like boot camp.” He assures that today, this argument would hold no ground. Therapy has improved tremendously, and recidivism rates of sex offenders have dropped rapidly in the past ten years.

In terms of chemical castration, there are other methods to teach a man to control his sex drives, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, which is a form of psychotherapy based on the idea that thoughts control behavior. As a result, a sex offender can change the way he thinks to feel and act better even if the situation does not change.

“I think in the beginning it was a wish-dream that people had back in the day that if we castrated the problem, it would go away,” Davis says. “But simply, that just isn’t the case.”

But Berlin is a firm believer in the effectiveness of the treatment, not only for the offender but also for the community: “I do think that it can be extremely helpful both to the individual himself and to the extent that person is safe to the community at large.”

Categories:

Chemical Castration

June 9, 2011

0

Donate to Ethos

Your donation will support the student journalists of University of Oregon - Ethos. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover