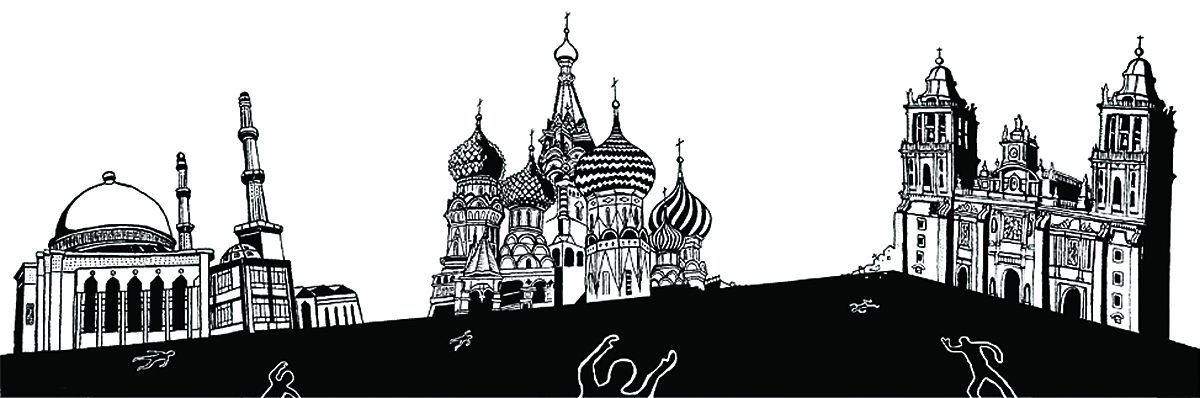

In their pursuit of truth, journalists face censorship and even death around the world

Story by Cody Newton

Illustration by Edwin Ouellette

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranks Mexico, Russia, and Afghanistan among the most dangerous places in the world to be involved in the press. Rampant corruption, as well as the lack of government protection and power, inspires violent groups such as drug cartels and terrorist organizations to silence journalists—by any means necessary. Despite the dangers of finding and exposing information in these countries, journalists continue to put their lives on the line to report the truth.

War in Afghanistan

Habib Zahori, a journalist from Kabul, Afghanistan, writes under the name “Asheel Qayum” to prevent the Taliban and other potential threats from kidnapping him. “We can’t write or talk about a certain number of individuals and their dirty business,” he says.

In January, Zahori worked on a story for the New Yorker in Afghanistan, exposing the corruption of Khalil Ferozi, the owner of the country’s largest private bank. Since the release of his article, Zahori has been forced to change his life. He now keeps his phone turned off during most of the day and won’t answer numbers he doesn’t recognize. Afghanistan’s constitution has had guaranteed press freedoms since 2004, but exposing corruption and expressing personal opinion still comes at a price for journalists in Afghanistan.

According to Zahori, constitutions are hard to defend in war-torn countries since the government is unable to enforce constitutional rights. “Warlords and strongmen are still in control of everything here,” Zahori says. “Those who dare to write the truth often end up either in jails or killed.”

According to the CPJ, twenty-three journalists have died in Afghanistan since the US-led conflict began in 2001. The war in Afghanistan has been increasingly dangerous for foreign journalists who face the decision of reporting as an embedded correspondent with the US-led International Security Assistance Force, or venturing out into the field alone without the aid of military

protection. Victor Blue, a freelance journalist based in San Francisco, has been to Afghanistan twice in the last two years: once as an embedded photographer with the US military, and once unilaterally to do work in Kabul.

Blue spent twelve days going on patrols in the Marja area of Helmand Province, the world’s largest producer of opium. He spent nine of those days in firefights. “There really isn’t a ‘front line’ in Afghanistan,” he says about his experience. “It’s an insurgency.”

Still, Blue chooses not to dwell on the dangers, as soldiers always suffer worse than journalists, and Afghani citizens “suffer worse than both of us.” However, those dangers are worth the advantages of gaining an inside view of the military effort. Blue was able to report outside of popular military bases and spend time on smaller patrol bases where soldiers are closer to combat.

“That’s where you can see how the troops are interacting with the Afghani population,” Blue says. However, “if every time you show up to take a photo wearing a helmet, body armor, and are surrounded by guys armed to the teeth, it’s going to affect how the Afghani people act in front of you.”

For Blue, this is where being unilateral has its advantage. “It’s being able to see the country as it is,” he says.

Despite the violence and dangers in this country, Blue feels he has a responsibility to represent Afghanistan’s marginalized people and share a glimpse of their culture through his reporting. “I can be the bridge between the things that demand our attention and the people who can’t be there,” he says.

Russia’s Media Control

Anna Ovyan was a journalism intern at the Moscow-based Novaya Gazeta when a well-known Russian journalist, Anna Politkovskaya, was murdered on October 7, 2006. Politkovskaya was famous for her criticism of former Russian President, and current Russian Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin, and her investigation of war crimes during the Chechen conflict. “It was a tragedy for the newspaper and its journalists,” Ovyan recalls.

A week before her suspected assassination, Politkovskaya told Radio Free Europe that she was a witness to a criminal case against Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov and accused him of being a “Stalin of our times.”

After the murder of Politkovskaya, Novaya Gazeta’s editor in chief Dmitry Muratov considered closing down the newspaper, and banned all journalists on staff from going into Chechnya. “It’s not easy to say that in our country these murders are not a surprise for us,” Ovyan says.

According to the CPJ, thirteen journalists have been killed in contract style murders, or pre-planned organized killings, since Putin took office in 2000. However, no one has ever been convicted of planning the murders. Some scholars accuse Russian elites for preventing these investigations as a way of controlling media.

Forbes Russia, owned by the independent German-based company Axel Springer, has also seen its share of tragedy. Alex Levinsky, a writer for Forbes, along with almost all of his colleagues, believes former editor in chief Paul Klebnikov was assassinated on July 9, 2004, for his investigation regarding corruption by Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky.

Levinsky himself has been threatened and bribed in his career. One of his first stories for Forbes was an investigative piece about the state-owned company Gazprom, one of the largest gas and oil companies in the world. He suspected the company was stealing money. While on assignment, Levinsky received two mysterious phone calls; one was from a member of the State Duma, the legislative branch of the Russian government. The man told him to stop working on the story.

He was eventually asked to meet with members of the KGB successor Federal Security Service (FSB in Russia), and was told “not to offend good people.” After the confrontation, he feared going to the police. At one point Levinsky even told his children, “If I call and it’s an emergency, you’ll need to stay away from the house for a couple days.”

Levinsky never had to make the phone call, but it was a sobering reminder of the lack of protection journalists are given in Russia. “The state speaks about the protection of journalists,” Levinsky says.

“But never really does anything to protect them.”

Mexico’s Drug War

Mexico’s Drug War Carlos Lauría, another member of the CPJ, tells the story of Rodolfo Rincón, a fifty-four-year-old journalist and employee of Tabasco HOY newspaper in Villahermosa, the capitol of the Tabasco region of Mexico.

As a seasoned criminal reporter, Rincón was used to getting threats to his life. During a time when rival gangs fighting for control over drug trafficking routes were resorting to beheadings, Rincón was producing a story that included photos of the criminals’ safe houses.

Rincón was last seen in January 2007 leaving his newsroom. Three years later on March 1, 2010, a spokesperson for the Tabasco State Attorney General’s office announced that Rincón had been kidnapped and murdered by the Los Zetas cartel, which the US government considers one of the most dangerous and sophisticated drug organizations in Mexico.

“Authorities found the burned remains of a body they believed belonged to Rincón,” Lauría says, although DNA tests never confirmed this.

According to the CPJ, twenty-two journalists have been killed in Mexico since President Felipe Calderón took office in 2006. Mexican journalists are guaranteed individual rights to freedom of expression and freedom of the press, but compared to the mounting influence of drug cartels, the government is powerless to enforce such rights. The problem, according to Lauría, is that “Corrupt state and local authorities remain largely in charge of fighting crimes against the press.”

As a result, the local press remains entirely defenseless.

“The government has failed to take responsibility for the widespread attacks on free expression,” Lauría explains.

After losing two journalists, the daily newspaper El Diario in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, published a front page editorial asking drug cartels, “What are we supposed to publish or not publish? . . . You are at this time the de facto authorities.”

Every day, journalists in Mexico risk their lives to report on a drug war that according to an administration report to US Congress, has claimed the lives of 22,000 people. Yet despite their sacrifice, little is being done to protect them. According to the CPJ, 90 percent of all press-related crimes over the last ten years have not been solved.

Brisa Maya of Mexico’s National Centre for Social Communication said in an Inter Press Service report, “the impunity enjoyed by those who attack and murder Mexican journalists leaves the door wide open for further attacks.”

That door may be wide open, but committed journalists continue to die in their efforts to inform the public. However, without support by the government, people like Lauría fear Mexican journalists may one day be completely silenced. “Pervasive self-censorship throughout vast areas of the country is the product of this lethal violence,” Lauría says.

Groups such as the CPJ understand the Mexican people want and need to stay informed, but without protection, journalists won’t be able to give the people what they need. “They know they’re at war,” Lauría says. “They want to understand what is happening and how to combat it.”