Outside of Luckey’s Club, a local Eugene bar known for live music and antique pool tables, a group of mostly young people are smoking cigarettes and talking loudly at each other. Blanketed behind a dense layer of smoke, a speaker radiates music from inside, which at the current moment sounds like an improvisational jazz set. Loud horns and keyboard strokes merely act as background music for lazy conversation and audible exhales.

A loud voice emanates from the speaker, cutting through the music and the nondescript bar chatter. “Where’s Brax? Brax comes to the stage.” The voice is melodic, as it rides a wave of instruments. One by one everyone begins to shuffle inside. Half-smoked cigarettes are put out early and hidden along the side of the building for later, others are tossed in the street or stuffed in purses and pockets.

Spencer Smyth, a local producer and hip-hop artist who graduated from the University of Oregon this past year, holds steady in the center of the stage. His blue button-down reminds me less of an MC and more of an insurance salesman. Yet he doesn’t look out of place. This past year, Smyth has been a staple at Luckey’s Wednesday night funk jam, a night where local musicians and MCs sign up to take the stage to perform music in a collaborative setting. According to Blake Boxer, who works the door for Luckey’s, the Wednesday night funk jam has existed in various forms for over three years. Most of the musicians that participate know each other and fall into a comfortable groove. A smile covers his face as Brandon “Brax” Parry moves towards the stage.

Both Smyth and Brax represent a loose collective of artists operating under the Breakfast Boys Leisure League Moniker. Recently, Brax released “Self Help Book,” his debut album, executive produced by Smyth. Their relationship is intensely collaborative, which in and of itself, goes along to help encapsulate the overall mission of the Breakfast Boys.

“When I first started it, it was supposed to be a tool of anonymity and a way to try to divorce ego from the music,” Brax says. “But it was also supposed to be a collective of sorts. A banner for any of my artist homies to put shit out under.”

According to Brax, Breakfast Boys will eventually encompass art from all mediums. Whether it be film, writing, music, or digital arts. It’s a place where anyone with a like-minded appreciation of independent content can share their material with a community behind them. It’s the same sort of vibe provided by the Wednesday night funk jams and the local open mics that both Brax and Smyth have been known to habitat.

On August 24th, Brax and Smyth began their first out-of-state tour. The “Spinitch’ for Breakfast” tour would take them from Eugene to Portland, where they’re not exactly strangers to the local music scene. The pair will then head south through California’s Bay Area and end back in Eugene on September 15th for the homecoming show at the Freedom Thought Fest. Having played every venue there is the play in and around Eugene and the university campus, this tour is a large step in broadening their scope as musicians.

Artists who perform in the same venues for the same crowds of people week after week, you can get a sense that the city might be too small for them. The stages which once housed unique experiences begin to crumble with familiarity and as Eugene’s population consistently recycles itself, so does your fan base.

The tour came at a perfect time for both artists. Smyth is transitioning out of college and returning to his hometown of Portland. He’s even turned the basement of his mom’s house into a studio. Brax just put in a two-month notice at his job with plans to move to Portland. To them, it feels like a “now or never” moment, building off the momentum they have from “Self Help Book” and the litany of live shows they’ve played locally on a weekly basis.

For the past two years, both artists have cultivated a stage presence built almost entirely on improvisation. They have been seen around the Eugene area, accompanied by a slew of Jazz musicians or freestyling over the sounds of UO math rock band Spiller. Sam Mendoza, who’s both a guitarist and vocalist for Spiller, has a long history of collaboration with both Brax and Smyth.

“I was able to pass on general advice about the realities of touring,” Mendoza says. “We’ve got mad love and respect for each other’s music and try to attend as many shows as possible. We did one show as a full band with Brax for the Self Help Book release party.”

Smyth having officially graduated in June will begin the daunting task of managing work while also attempting to give one hundred percent to a slowly growing hip-hop career. It’s easy to be creative at a university that encourages art. If you’re privileged enough, these four years of your life are practically reserved for exploration and self-expression. For many people, graduation can act as a reality check. A time to buckle down and focus on landing a job with stability and structure. However, the decision to devote himself to hip-hop was never a tough choice for Smyth.

“Music and collaborating has consumed my life for the past two years at least,” Smyth said. “And as the stakes get higher, the amount of time I spend producing and growing as an artist will only increase. I won’t quit. I want to make a living from music, so I can live to make music.”

Brax, who originally asked to keep his first name out of the story, seems to be content with letting the music speak for itself. “Self Help Book,” doesn’t stray from the autobiographical, but it does require some searching if you’re going to piece together the personal life of a man who knowingly hides behind an encyclopedic knowledge. It’s a well-thought-out maze of obscure references, managing to feel intensely personal and anonymous at the same time.

After graduating high school in 2010, Brax took an entirely separate road to arrive at the same conclusion as Smyth. While Brax has never stopped writing and consuming music, he explains how he’s quit rapping around four separate times.

“My relationship to music is similar to a smokers relationship to cigarettes. I want to quit but I can’t,” Brax said.

After college, Brax was too consumed with surviving to focus on living through hip-hop.

“It’s not easy being a rapper with a full-time job. I was making beats and whatnot, but I had to buy groceries. I sold my beat machine for groceries. The laptop I used for school broke. I still haven’t gotten a new computer. I just didn’t have it in my head that I wanted to be a rapper,” Brax said.

A large amount of Brax’s inspiration comes from relationships he’s built with his collaborators and friends. It was a combination of feeling unfulfilled at various jobs and the constant badgering of a few good friends to come and perform at Lucky’s funk jam, that helped Brax get out of his own funk and began placing value in the creation of art and hip-hop again.

“All of my close friends have always had a passion for hip-hop or music of some kind. It’s second nature to me. It’s not something I want to do, more so something I have to do. On most days I can’t imagine not writing something down. It’s cathartic for me,” Brax said.

There’s no guarantee that music will pan out for either Smyth or Brax. He knows this intuitively, partially due to a built-in skepticism, but also from experiencing first hand what it feels like to be poor. The idea of the starving artist is nothing new. It’s attractive when someone chooses art over society. A feeling over necessity. But even a starving artist will tell you, the goal is to have both. The thing I love about Brax is this whimsical pessimism; even if his glass is half empty, he’s still having fun drinking it.

In contrast to Brax, Smyth exudes positivity. It’s the logical conclusion of someone who is riding that feeling. It’s the feeling you get when music gives you chills and you can’t quite explain why. It’s what happens to your body when a song reminds you of someone you’ve loved. Except I get the feeling that Smyth feels this about hip-hop in general.

Smyth, whose collaboration with Portland rapper Este came out this past January, belongs to a class of MC who still places value in the art of freestyling, managing to incorporate the unwritten word in nearly every one of his shows.

“Freestyling is in my blood and that is both literally and figuratively a part of 95% of my shows,” Smyth said. “I want every show to be different. It just doesn’t feel right to do too many of the same rehearsed theatrics from show-to-show.”

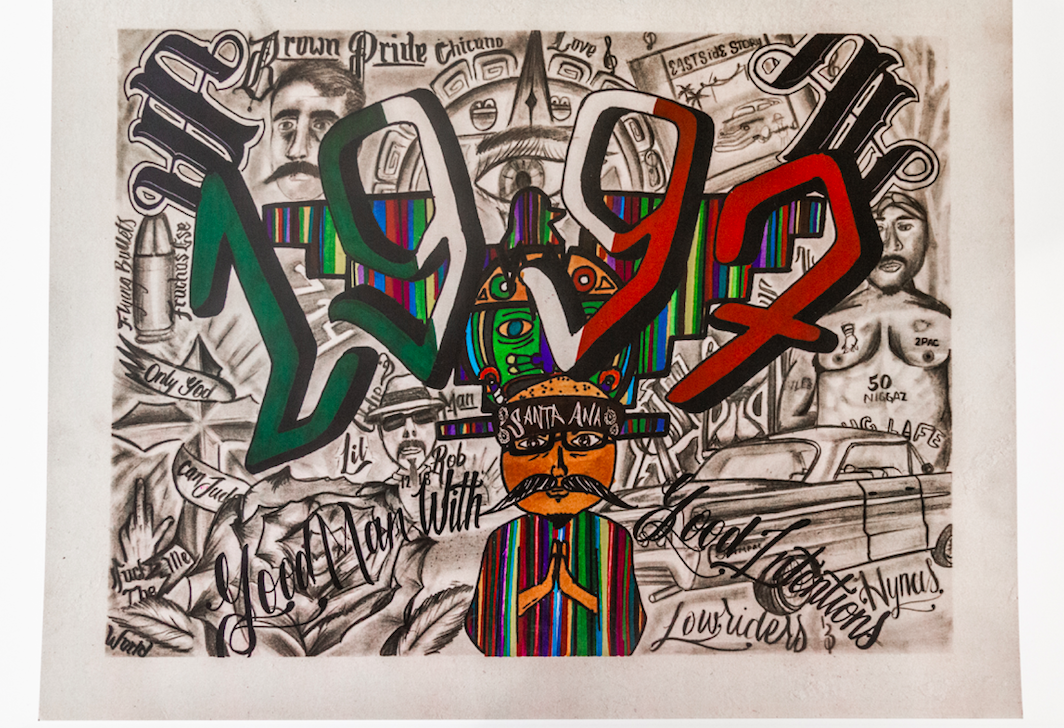

Listening to Smyth’s music is like stepping into a time machine and travelling back to the mid-90’s, where New York boom-bap reigned supreme and the MC’s had to be skilled enough to ride the drums. Auto-tune hadn’t been invented yet and rappers who dared to sing their own choruses got roasted for lacking the masculinity to ask Ashanti or Jennifer Lopez to do it. Smyth’s music is infinitely rewarding, he’s constantly referencing and sampling artists who have influenced him. Even his T-shirts are designed after the 1983 film Wild Style, a film that captured a moment in hip-hop history in an unprecedented way. The film showcased not only music but art, dance and fashion. It showed hip-hop as a way of life.

“I think a certain amount of obsession is healthy for an artist,” Smyth says. “And I’ve been fortunate enough to have the opportunity to be surrounded by people who genuinely accept each other’s unwavering passion for music.”

Smyth has a wide range of inspirations, from early soul band Earth Wind and Fire, to Steely Dan and all the way up to Aesop Rock. But he’s also inspired by things like Nature and socializing. He’s a person who recognizes that every small interaction can be turned into inspiration. For Smyth, it’s almost as if nothing is ever not about music. “I’m always working on a ton of different projects,” Smyth says. “Most of my close friends are collaborators, and it’s not like that’s a requirement for friendship, but it definitely has worked out that way in the past. I’m attracted to people who love music.”

When not working on music, Smyth spent his time at UO double majoring in Spanish and ethnic studies. Outside of class, he took advantage of the many music opportunities that UO offers, including being a weekly DJ at the university radio station, KWVA.

“I loved DJing at KWVA because it was a space to play anything I wanted and discover my passion for records and live mixing on turntables,” Smyth said. “I met so many musically inclined people that I’ll probably know for the rest of my life.”

It was at KWVA, that Smyth met Brax. They instantly connected through their knowledge of hip-hop culture and random sports facts. Nearly every facet of this tour and these artists history together can be traced back to the UO.

UO has always been a spot where artists could meet and have not only the space for artistic expression but also a platform to display it. The name Breakfast Boys is even inspired by Brax’s brief stint as a host at The Glenwood, a local campus breakfast spot. The contacts that book shows for the tour came from a UO band who they met at local shows. The community fostered around campus was arguably more important as the educational aspects of attending school.

On the way to California to perform the first out of state shows of their career, Brax’s 1998 Honda Accord struggled to make it over the winding hills that separate Oregon from the Golden State. Smoke and ash from forest fires created a grey filter, which consumed the otherwise green and vibrant plant-life that surrounded the highway. Throughout the trip, Brax and Smyth received conflicting information regarding whether not the interstate would even be open for use on their way back to Oregon.

The first three shows of the tour happened in Oregon: Eugene, Corvallis, and Portland. The Portland show was unique because nearly every MC featured on “Self Help Book,” was there to grace the stage for the rare live posse cut “Couldn’t Do It.” It would prove to be one of the best shows of the tour, easily attracting over 100 people in one of the larger venues Breakfast Boys has ever played. It was a proper send-off for a tour that became wrought with unpredictable attendance and last minute cancellations.

The first two California shows took place in Berkeley. Known for being the birthplace of the 1960’s free speech movement as well as the hometown of rapper Lil B, Berkeley has a long history associated with freedom of expression. There seems to be a never-ending series of shows happening every night of the week. Through personal connections, it wasn’t hard to book the venues and get paid small amounts of money for performing. It was the first instance, but not the last, of venues underpaying their performing artists.

“I wasn’t surprised,” Brax says. “I didn’t really have expectations for the shows since we’d never been there before. We definitely weren’t there for the sole purpose of making money either.”

According to Smyth, the shows on the tour were slightly more planned out than the shows they were used to performing in Eugene.

“We came into it with a little more of a plot than usual, but still wanted every show to be different,” Smyth said. “For us right now, some shows could have 15 people, some could have over 100, so I think it’s beneficial to go into each performance with a malleable-energy — a willingness to vibe differently on any given night.”

In-between songs, Brax and Smyth displayed a playful chemistry usually reserved for best friends or siblings. They could often finish each other’s sentences in a way that was neither rehearsed nor predictable. The effortless banter makes you feel as if you’ve been let in on a little secret, one you expected to be true the entire time but needed it said to believe it. It’s this relatability that attracts fans of all genres of music. Not to mention that UO band Laundry opened for Brax and Smyth, more than once while in California, always inviting them up to freestyle over guitar riffs and heavy drums. Laundry’s guitarist and vocalist, Riley Somers, jumped at the opportunity of touring with the Breakfast Boys.

“We contacted Breakfast Boys through Facebook earlier this year. They offered us the gigs and got us on the road,” Somers said. “At every California show, we had Smyth and Brax spitting bars over some of our funkier tunes. We love meshing genres and jamming on the spot.”

The San Francisco show was held at the Honey Hive art gallery on September 9th. Known for their intimate performances and a smaller venue, the room felt oddly full by the time Laundry finished their set. Smyth took the stage to begin setting up his equipment. Tucked away in a residential neighborhood, the Honey Hive was strict about the music ending by 10 pm. Breakfast Boys were late to go on and weren’t able to play their full set.

“It didn’t bother me,” Brax said. “I’d rather keep it short and have people wanting more as opposed to playing too long and having people get bored.”

The best show on tour happened on September 12th, in Chico, CA at the Naked Lounge. By the end of the show, people were approaching the merchandise table and asking Brax and Smyth to sign yellow Breakfast Boys T-shirts that they had purchased after their performance. The foster father of 17-year-old rapper Apollo Snow, who played after the Breakfast Boys that night, came up to Brax and Smyth after the show to tell them how important they were to the genre. Apollo Snow, who’s music is incredibly indebted to the Soundcloud rap that came before him, sounded sonically different from Breakfast Boys but reminded me of the similarities between the two acts.

The Soundcloud rapper is content with taking a minimalist approach to making music. A hot beat, an extended chorus, a catchy phrase, or accompanying dance is, theoretically, all one needs to approach the hedonistic brand of modern-day radio rap. Unsurprisingly, this simultaneously excites the younger crowd while infuriating the older generations. The pairing of Brax and Smyth doesn’t just bridge the gap between 90’s boom bap and contemporary swag rap. Both on and off stage, neither artist is comfortable attempting to be something they’re not. Any shameless bragging is accompanied with a healthy dose of self-deprecation.

The journey of Brax and Smyth is far from over. They have unreleased collaborations with each other as well as artists loosely connected to both. Their experiences rapping and travelling together has only reinforced the feeling that it’s now or never. As the venues change, and the crowds begin to blend together, the mission statement remains the same.

“I want to make music with as many people as possible. Brax said. “I’m just trying to do all the weird art stuff with my friends before I die, or before the world blows up.”

Brandon “Brax” Parry of the Breakfast Boys Leisure League maintains a non-traditional stage presence for a hip-hop performer, at times angstily screaming into the mic or contorting his body on the ground. (Sarah Northrop/Ethos)

![Words | Renata S. Geraldo Art | Maddy Wignall   Sex trafficking takes on many different forms. Women from poor families fall victim and are kidnapped or sold into prostitution. In the United States, prostitution and trafficking take a different form. Trafficking happens through coercion and manipulation; a much subtler […]](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/8ad948459029f9a809f9628092dca222.png)

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)