“Today’s the day.” That was Sergio Sanchez’s first thought when he woke up on February 15, 2019. It was a rainy, gloomy start of a day that would change Sanchez’s future. Starting at 5 p.m., he would have his first gallery opening in the EMU, called “Sergio Sanchez: Santanero y Mexicano.” He’d been preparing for this day for months now. He flew his mother in from Santa Ana, California, and bought fresh new clothes for the opening.

But Sanchez had his whole day in front of him. He went to class and worked, and later ironed his clothes in the bathroom behind the Multicultural Center in the EMU. What he wore, he said, communicated his identity as a Chicano: 501 jeans from Levi’s, white and blue Nike Cortez shoes, a white ProClub shirt, a straw hat and a sarape (a loose sweater) across the shoulder with Aztec symbols.

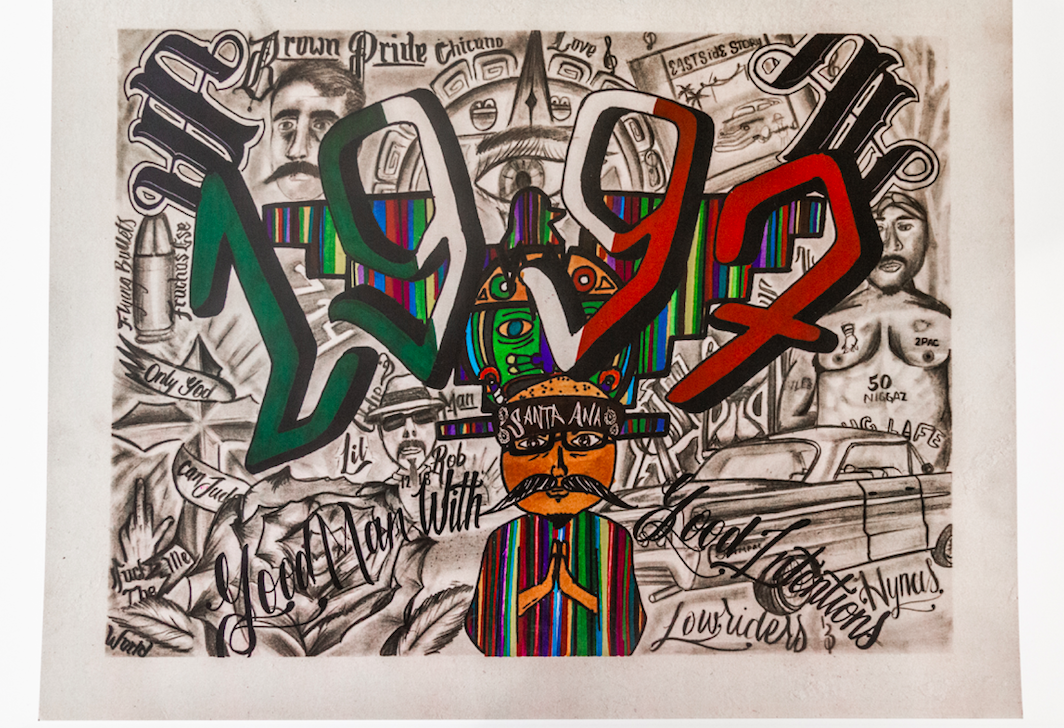

The art on the wall of the gallery expressed his identity: his pride of being Chicano, the love he feels for his family and friends, the struggle of being a student of color in a white campus and the fear of failing his dreams.

His artistic style, which Sanchez calls the “Sergio style,” is busy art. On a single piece of paper, he expresses his identity through lettering, with sentences or words often written in Spanish, drawings of eyes, Aztec symbols and love letters written to his girlfriend or mother.

Though he was scared that no one would show up, his art gallery quickly filled up with people. From faculty to co-workers, his mom and his girlfriend, about 100 people, coming and going, filled up the room. It poured outside, but inside the gallery, Sanchez was surrounded by the warmth of people and traditional Mexican food. There were conchas, (Mexican sweet bread with sugar or chocolate sprinkled to the format of a seashell on top), flan (a sweet similar to custard), juice and hot beverages. Though UO Catering does not often offer these traditional Mexican dishes, Sanchez says that they did it just for his opening.

This was the moment that everything changed for Sanchez: when he saw how much he had evolved as an artist and that he had a future in art. Surrounded by friends, co-workers, faculty, girlfriend and mom, Sanchez stood up on a wooden stool to give a speech and thank everyone who was there.

He’s not one to show emotions outside his close circle of friends and family, says his girlfriend Vanessa Carrillo, but as he went up to give the speech, his emotions overwhelmed him and his eyes were watery.

Sanchez’s art is shaped by his roots coming from Santa Ana, California. According to data from the city website, Hispanics are 78.2% of the population there, followed by 10.4% of Asians and 9.2% of Whites. It’s an area shaped by Chicano culture: lowriders, graffiti and pride. But while he was part of the culture in Santa Ana, Sanchez now stands out in Eugene, where 9.4% of Hispanics or Latinos contrast with 84% of Whites, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

For Sanchez, being a Chicano means being Mexican American. In other words, he has the culture of a Mexican, but inserted in an American socio-political landscape. He’s often dressed in oversized jeans and shirts (sometimes button-ups) and he wears his hair back. Many people see him as a cholo, a Mexican gangster, but in reality, Sanchez says he looks like a normal Chicano.

Carrillo says that the way he presents himself and his art is what attracts — and deflects — people. He’s often misinterpreted, she says, and this goes the same for his art. But Carrillo says that this misinterpretation is also what moves him forward.

“I think a lot of people misunderstand or misinterpret him,” she says. “People see him and automatically think he’s probably from California, a Chicano, all this stuff, and I think that that’s helped him really make connections with faculty members or students. I think with the most successful people you’ll find that they’ll have the same thing that helps them is the same thing that puts them back sometimes.”

In most of Sanchez’s pieces there is an element of brown pride, or pride of being Hispanic. In an older drawing, he wrote, “Orgullosamente Mexicano” (Proudly Mexican). In a more recent piece, he wrote, “Brown Love.” But along with his Chicano pride, he says, he tries to ignore the bad parts of his roots in Santa Ana, like gang violence.

He dealt with gangs growing up, though he was never involved in their activities. Sanchez sees himself as a traditional Chicano, but the gangs around him never liked that he would behave and dress differently from them, as if Sanchez were a threat to their rules. He would keep his style, which, he says, is much influenced by lowriders and traditional Chicano clothing, such as Nike Cortez shoes, 501 Levi’s pants and ProClub shirts. But by doing so, he says he was scared that he would be attacked at any moment.

Sanchez says what kept him away from getting in trouble and towards college was art and sports.

His art career started earlier. In elementary school, he began imitating his brother’s graffiti art. But art became an obsession for him when he developed his “Sergio style,” which is the same one that was exhibited in the EMU earlier this year. He says he started developing his style when shifting from graffiti to a Chicano-style drawing and lettering related to lowriders and Mexican culture. One of his dreams when he was younger and before the gallery, he says, was to airbrush one of his pieces onto his lowrider.

In middle school, however, his art was seen by school officials as slacking off. He was also told that if he got to high school, he should take art classes to learn how to do what they considered to be the “correct,” traditional art. He says he got his Sharpies taken away from him and got suspended for carrying them around in his backpack. But Sanchez carried on, he says, because he would use his art to flirt with girls.

He began doing track and field in high school and heard of the UO as a freshman when a fellow senior student compared him to Steve Prefontaine (“Pre”), UO’s famous track athlete. He was accepted to the UO, but his problems were not over.

When he came to Eugene, he didn’t have to deal with gangs anymore. Now, the threat was bigots.

In a warm, dry Wednesday in May at 6:30 p.m., Sanchez and his team played their last intramural soccer game. They were there to have fun, says team captain Hanzel López, because they wouldn’t make it to the playoffs. Called the UO B3ans due to most of the team members being Latinx, it would be the last time in the year that they would wear their white shirts with UO B3ans written in green across chest. They were playing against a fraternity, says López, and the game was peaceful until the latter half of the game.

López says that the other team started calling them names and being more aggressive than normal for a soccer game. He remembers being mocked because of his height and being asked if the UO B3ans had drank too much cerveza (“beer,” in Spanish).

Tensions started to build up. López said that people from the other team were asking the UO B3ans to hit first so they could call the police. His teammates were, above anything else, confused. They were already losing 3-0, he says, so there was no point in being provoked.

López says the referees for the game were not doing anything to stop the tensions. The UO B3ans goalkeeper asked to end the game before the time limit. Instead of fighting, each team went in different directions, López says. His team was still confused as to when and why the tensions started, but the verbal racial aggressions, he says, were common.

“I could easily knock that foo out,” Sanchez said about one of the students from the adversary team. “Either he goes down or I go down.”

What kept Sanchez from hitting someone, he says, was the fact that, in a white campus, he and his teammates would be the ones to get in trouble, regardless of who would win the fight.

“It took a lot out of me to be, like, you know what? This guy’s not important. This is a soccer game,” he says. “I’m not ‘bout to ruin my education, the education of those people that are playing with me, the other brown people around me because of this piece of shit.”

In one of his most recent pieces, Sanchez drew jail bars with a blue pen. It does not take most of the painting compared to a rose and letterings that say “Californiano” and “Florita del alma.” But the drawing of the cage is present in a much smaller scale in the background of the upper left corner.

Carrillo says that his baggy clothes and cool exterior can sometimes be threatening to ignorant people, but Sanchez is sensible inside. In the same painting, Sanchez drew two eyes – one by itself and another in a woman. He also wrote, “It’s in the eyes, chico.” The eyes are one of his favorite things to draw, he says, because “the eyes are the door of a person’s emotions.”

He says he is very emotional and “feels more than the average person,” but Sanchez doesn’t let his feelings transpire. For better or for worse, if he let his emotions get the best of him, he might get in trouble.

“He reacts on his emotions a lot,” said Carrilo, “and that might get him in trouble sometimes, but that’s not always bad.”

Sanchez’s art depicts a lot of women, either through lettering or drawings. The eyes that he draws are often feminine. When he draws women, they often have long hair and a hat, and in one of his recent drawings, there is a bare-breast woman.

He says he feels a lot of connection with women due to being raised by his mother while his father was out working. Because of this connection with his mother, Silvia, he flew her to Eugene to see his gallery. He says he wasn’t sure she would be able to come. She’d just gotten back from Mexico and had missed a few days’ work. But she came nonetheless to spend one of the most important days of Sanchez’s life with him.

Yet in one occasion, Sanchez let his feelings get the best of him. He was listening to 2Pac without headphones next to Fenton Hall one day while he was walking out of class, when a female student passed by him and made a comment about his music.

“2Pac tends to curse a lot in his music and she said, ‘Oh my God, that music, why is he cursing so much, like, turn it off,’” said Sanchez. “That’s when I said, ‘fuck you, bitch.’ I shouldn’t have said that, but, at the same time, why do people feel so uncomfortable and automatically disrespect or say something? I’m just passing by.”

That was his first reaction. Looking back, he says he shouldn’t have said “bitch,” but she caught him off guard.

The stakes were higher for Sanchez after his gallery, especially for him as a student of color who says people expect him to fail. He says he knows that there are people who would give everything to be in his shoes, so he can’t afford doing things that can threaten his position at the UO.

Sanchez says he expects everything from himself: to be happy, successful, to have a career, a family back in California. But his anxiety and impatience are some of his biggest challenges.

“At the end of the day, I come from this place where we’re quick to react,” he says, snapping his fingers. “I have so much to give and so much more to lose, and they don’t. For all I know, they got money. For all I know, they don’t care about school. For all I know, if they get kicked out, they’ll go to another one. If I get kicked out, where am I going to go? Back home, back to the same shit I was in. I don’t want that for me.”

In one of his most recent pieces, he wrote at the top of the page, “Don’t Put Me Down Cause I’m Brown.” He knows he has much to lose, but also much to gain if he keeps his emotions under control. But coming from an environment of constant vigilance, he could snap at any moment. “It makes my art mean to much more,” he says.

He cracked his neck both ways while talking about his experiences dealing with racism at the UO, and said that it’s what he does when he gets tense.

But when he started therapy at the UO, he said he learned how to better deal with his anxiety and stress.

“I would start tripping, overreacting, it could be the smallest things,” he says. “But then after these therapy things, I’m able to process what I’m feeling.”

He says he would be more impulsive, wouldn’t know how to handle or understand his anxiety or frustrations. “It’s easier for me to process things and understand how to communicate that,” he said.

Sanchez wants to work with youth, he says, so he can give them better opportunities. He also wants to give back to his family and his community in Santa Ana. The gallery, he said, was when he realized that he could dream big and see how he could succeed not only in art, but in whatever he chose to do, such as working with youth to help them thrive as well.

“How am I supposed to give to these kids if I’m going to react like that?” He said. “How am I supposed to help them if I can’t even help myself?”

Through his art, Sanchez says he’ll be able to attract kids to talk to him because “art attracts everybody.” And his gallery was the first step towards his success – having a family, giving back to the community, doing art, being proud of his identity and helping youth to have more options and ultimately succeed.

Art by Sergio Sanchez, photographed by Marin Stuart.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)