Words and Photos by Kendra Siebert

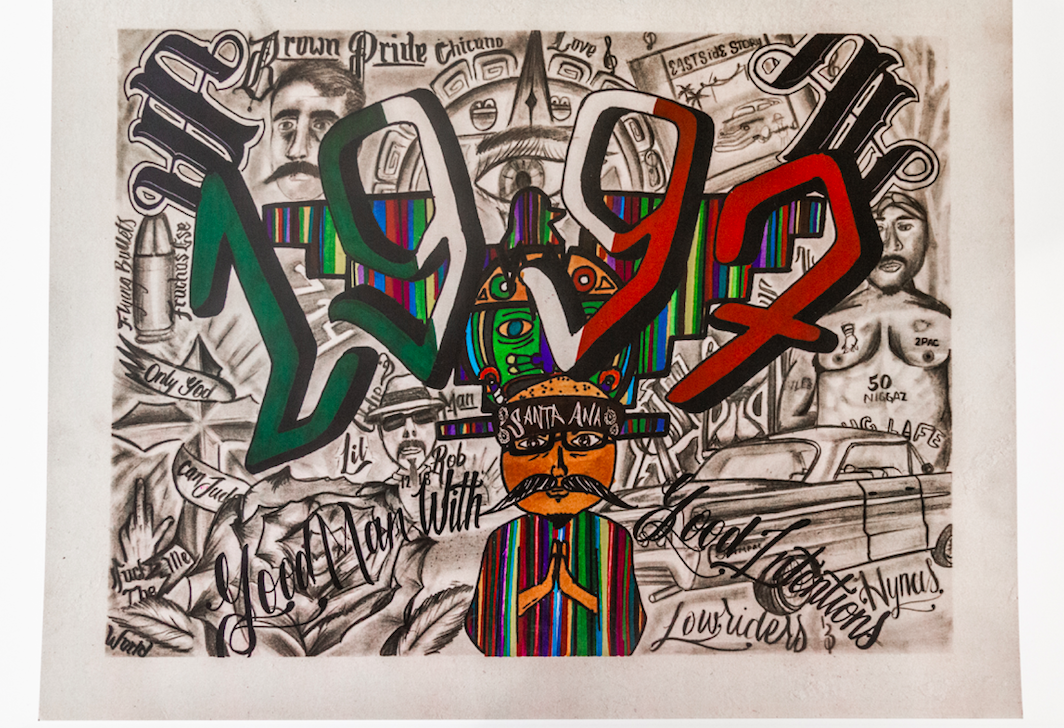

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]fter a full day of leading workshops at César E Chavéz Elementary School, Samuel Becerra returns to his apartment to continue making art. With hands stained light blue from the acrylic paint used at the school, he opens the door of his second story apartment and walks inside. From the outside, the pale white complex blends in with the other units lining River Road. The vibrant interior tells another story. Clay sculptures fill the living room shelves. Carved animal masks hang from the ceiling. Drawers brimming with art supplies border the walls, infringing on kitchen counter space and highlighting that art bleeds into all aspects of Becerra’s life.

Becerra’s creative journey began in Mexico City, where he spent the first 18 years of his life learning about Mexican folklore and Aztec history. Before immigrating from Mexico City with his parents and four siblings in 1990, Becerra became a skilled musician and received training in wind and string music. But his creative expression stalled once he left his tightknit community for the distant Eugene, where he initially struggled to maintain his Mexican identity. “I kind of lost my culture for a couple years,” he says.

After attempting to acclimate to a new way of life, Becerra felt impassioned to stay connected with his roots. He found the arts to be the medium that helped him both bridge the cultural gap and maintain his cultural identity. The more time he spent in Oregon, the more enthusiasm Becerra found for embracing his Mexican heritage and for sharing the tradition of his ancestors with people in the United States.

He first started sharing these traditions nearly 10 years ago, when he immersed himself in an investigation of Andean music. Much of the music he chose to explore started in ancient Aztec civilization more than 800 years ago. Becerra says the Aztecs built instruments that were meant to “imitate the sound of nature.” He had difficulty finding ancient flutes to play and ultimately realized, “the only way you can get these flutes is you have to make them.” So he did.

After spending 18 months researching the flute-making process and receiving formal training from a professional flute player in Los Angeles, Becerra officially began creating his own flutes using the same techniques and tools as the Aztecs did in the year 1200. “There are stories in every instrument,” says Becerra, holding one of the first flutes he ever made.

He painstakingly created dozens of these flutes and decided to bring the stories of the Mexican people to a younger generation in the Pacific Northwest. He began leading flute-making workshops in elementary schools and has found education to be another way to connect with his Hispanic roots. Becerra helped students create 8000 bird flutes last year alone and personally shaped each individual mouthpiece to play the sound of nature.

Along with instrument building, Becerra has found educational workshops to be a positive way to bridge the gap between his Hispanic and American cultures. Becerra is one of two Latinos who teaches about Latino culture full-time in Lane County, and he feels a sense of responsibility in helping others connect with his intersectional cultures.

Once in America, he also began exploring catrina sculptures. Becerra grew up with the catrina tradition in Mexico City, as people placed the catrina ceramic skeletal women on altars to commemorate Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead). But he only truly connected with the tradition after moving away from his community. According to Becerra, the catrina tradition began as propagandist response to the social classes that influenced society. What attracted him to these was that, “when people die, we all end in the same social class — there is no social class. Everybody belongs in the same social status.” Becerra models his catrinas after figures and clothing from different regions of Mexico and sells them at a yearly catrina exposition in Seattle, WA.

“I’m very fortunate that I do art for a living,” Becerra says. “All my activities are around the arts, somehow.”

Becerra travels around Oregon, Washington, and California as a means of selling his art, leading workshops, and performing. At this year’s Cinco de Mayo Festival on the Portland waterfront, Becerra performed with one of his bands, Los Cumbiamberos, and later led kid’s craft workshops near authentic Mexican artists’ booths.

Becerra has not returned to Mexico for 21 years. Although he is physically rooted in the states, his life is still greatly defined by his Mexican culture. In the future, he hopes to visit his family home with his two teenage daughters, who have grown up hearing stories secondhand. Sometimes when he shows them an image of his childhood home, Becerra wistfully observes, “this is part of our life, where we grew up… It’s a different life. It doesn’t matter how many years you’ve been here. You’re always thinking about where you came from.”

Unlike many other catrina artists, Becerra creates each doll from scratch and hand paints each one over a duration of many weeks. “You can see these beautiful dresses, but at the end, everybody ends up in the same place,” Becerra adds.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)