Linda and her granddaughter had an eccentric routine: using a mini shopping cart and going “shopping” in the kitchen. I would stand by, coloring the pages her granddaughter pushed towards me with eager eyes and watching her load the cart while Linda smiled. I thought, “If I don’t have that when I’m old and gray, then what is the point?”

I work in home healthcare, and I assist elderly clients, like Linda, in and around their homes. When I was first hired for the job, I had no caregiving experience. I didn’t even want to work in healthcare. But the significant pay raise the job would give me was incentive enough to apply. I had previously worked in many places, never finding the right fit. I knew I liked helping people, and seeing the way I could positively affect them. I saw the job listing on Indeed, and with a well-played cover letter and a follow-up email, I was hired.

On the first day of training, it was made clear we should not get too close to the people we care for — that we must maintain a sense of sterile professionalism. When a large part of home healthcare is spending time with and talking to clients, it’s hard not to get attached. They tell you their triumphs and downfalls, and we are encouraged by them to share ours. They become our homes away from home, our friends we help around the house. If you have a recurring client that requests you as their main caregiver, then it’s almost impossible to remain impartial.

Linda, who is using an alias for privacy, was a woman in her early 60s who lived in a trailer with her husband of over 30 years, her stepson and his girlfriend. She was assigned as my client, and we hit it off immediately. She was quiet with a sarcastic streak. We would spend our days going to thrift shops, playing board games or baking. We would sit on her bed and talk, every inch of her walls adorned with photos of her family, drawings from her grandchildren and the dolls she would hold to ease her into sleep.

As I was brushing her hair one day, she spoke softly about her past. She told me stories of her stepfather and the abuse she experienced from him, and how her mother knew, but chose to pretend she didn’t. She would occasionally look up at the picture she had framed of them while she talked.

Linda had been through many traumas that caused her to become a haunted house –– plagued by sorrows and hurt. Many people choose to use drugs to self-medicate traumas that haunt them. This self-medication can lead to addiction. The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as “a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences. People with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences.”

Like many others, Linda struggled with addiction and substance use. She was ashamed and said she hated talking about it. But she needed to get it off her chest to help her heal from a lifetime of hurt. She had relapsed about two months before she met me, as she was at a low point in her life. With the challenges of her disabilities and mental illness, she felt isolated from the world. She was growing older, so she couldn’t get out of the house and socialize like she once did.

She had started spending time with her stepson’s girlfriend, who we’ll call Devon. Devon was 22, and she gave Linda a rush of youth that eased her depression and bipolar disorder. However, Devon was actively using substances.

They bonded over their shared experiences, and Devon gave Linda a hit of meth. Linda, who had not used any substances for over 20 years, went into convulsions and was sent to the emergency room. Staff at the hospital labeled it as a suicide attempt, and she was sent to rehab after they stabilized her.

Linda said she wanted to take the hit to connect with Devon and distract herself from her sometimes rocky marriage. Most of all, she wanted to escape her loneliness. According to the American Society of Addiction Medicine, “addiction and loneliness are closely linked and often mutually reinforcing. Treating addiction is a priority when addressing the loneliness epidemic… loneliness is a risk factor that drives the use of drugs and alcohol.”

Linda was lonely, spending her days only with caregivers. She tried to connect with Devon, but it dragged her down to a life-threatening point.

Belle, who is also using an alias for privacy, is another person who works in home healthcare and has witnessed addiction and loneliness. She recently had an older client who lived in Eugene with her husband. When Belle stepped in the house, she noticed a woman with a light blue nightgown on, sitting in an old recliner that rested on stained carpet. She smelled rotting fruit and heard faint chings and canned laughter from a television show.

“The ambience of the home was very melancholic,” Belle says. “She was very positive, but when she started talking about her husband and what he was going through, it all came crashing down.”

The client’s husband was struggling with addiction. While it was a problem before their marriage, it had stopped. But a sour couple of years brought back the need to self-medicate, and the medication of choice? Heroin and crack cocaine.

“He would use it in the house, or leave and be on the streets. Do it there for a couple of days. She tried to get him out of it, and he has too, but it didn’t go anywhere,” Belle says. “When she was telling me [about her husband’s drug use], she was tearing up. She was trying to stay tough, trying to keep herself together. I just tried my best to be there for her while she talked about it.”

The opioid epidemic has hurt communities around the nation. We see television broadcasts of people experiencing withdrawal or homelessness. We also see glamorous portraits of drug use depicted in movies, online and just about every medium that shows the outrageous lifestyles of the elite. Oftentimes, substance use is seen as one step removed, that it “doesn’t happen that often.” It is ignored, repressed and talked about with shame. It’s a dark smudge on a white carpet you try to hide with that old recliner.

38% of American adults battled a substance use disorder (SUD) in 2017. 9.5 million or 3.8% of adults have both an SUD and mental illness –– like Linda.

When Belle spoke to me about her client, my mind kept wandering back to Linda and how tender my time with her was. Many similarities arose between my experiences and Belle’s: the sweet touches that accompanied the homes, the brave exteriors our clients presented. If you peered into the windows of their homes, you would never suspect the stories they told and the ones they were still creating.

When I moved for college, Linda was heartbroken, and I was too. It felt like I was losing a friend. Linda was not only losing a friend, but someone she trusted to care for her. When we said goodbye to one another in her room, she took two clown dolls off her wall and pressed them into my hands. “These are yours,” she said.

I wasn’t allowed to take anything from my clients, but she insisted. If I didn’t take them, she said she would throw them in the trash. They look at me now as I recollect my memories and put them down in this article.

While Linda and others have struggled with addiction, there are many paths individuals can take to manage the disease, and none of them look the same. “Addiction treatment is not a cure, but a way of managing the condition. Treatment enables people to counteract addiction’s disruptive effects on their brain and behavior and regain control of their lives,” the National Institute on Drug Abuse states.

Relapse is almost always guaranteed, but it isn’t a failure. Recovery is a slow process that involves addressing what the National Institute on Drug Abuse calls “deeply rooted behaviors.”

In Eugene, there are many facilities individuals can access for help in their journey against addiction. Emergence Addiction is a counseling-based treatment center that focuses on mental health and SUD. Direction Service Counseling Center also offers treatment paths ranging from individual psychotherapy, trauma therapy and behavior therapy. If you or someone you know needs immediate help, you can call the Behavioral Health Resource Network of Lane County Hotline at 800-422-2595 or dial the Suicide and Crisis Hotline at 988 to talk with a person who can listen and offer help.

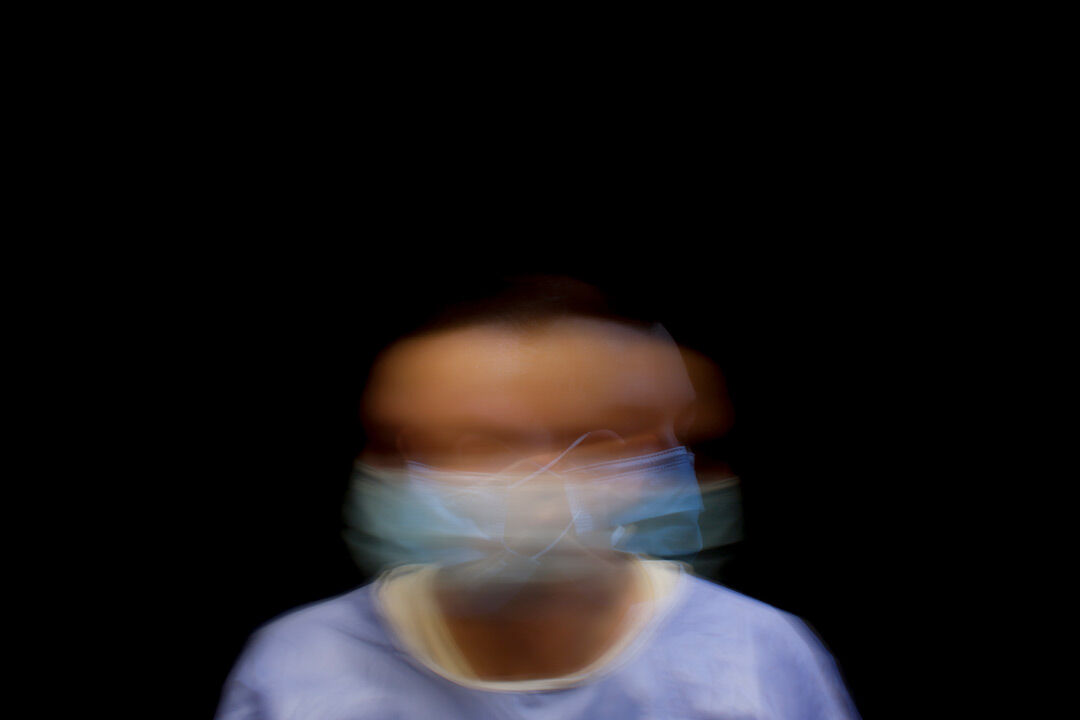

A model dressed to resemble a healthcare worker holds the dolls Linda gifted Alice. Many people like Linda, who struggle with both addiction and mental illness, lack treatment. Only 51.4% received mental health care or substance abuse treatment, according to the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics. (Alex Hernandez/Ethos)

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)