On Friday nights, the green house on the corner seems to glow. Possibly overlooked during the day, it takes on a new warmth by 6 p.m., when the front window is filled with the silhouette of several dozen people sitting together in a candle-lit room. There is music spilling out the front door each time it opens for the gentle stream of visitors. This is Oregon Hillel.

Oregon Hillel, the state’s chapter of Hillel International, is a Jewish student community center that serves University of Oregon and Oregon State University students. They hold Shabbat, traditionally a Jewish time for rest and prayer, every Friday night. The entire evening, from the service to the free home-cooked dinner after, is open to anyone who wants to come.

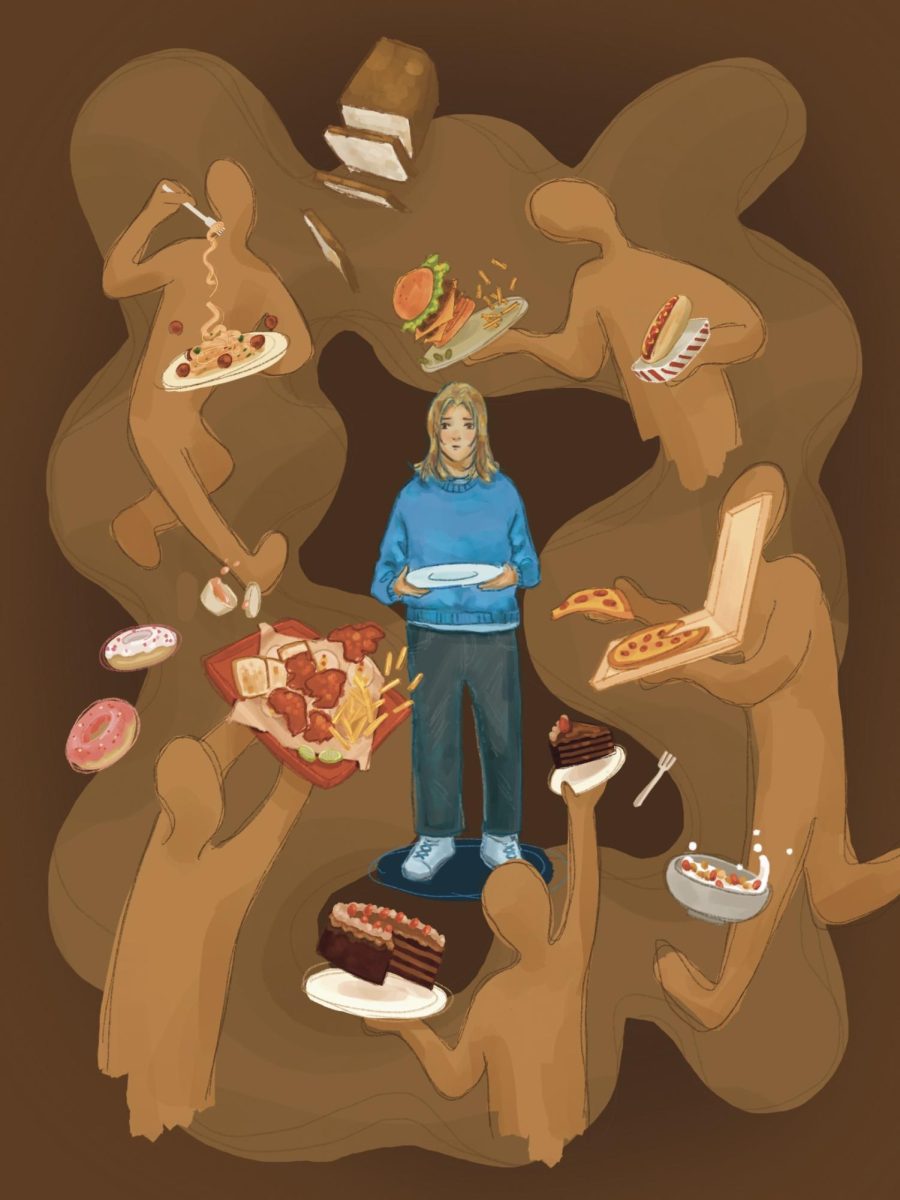

Hillel serves as a center for students figuring out who they want to be as they move into adulthood. Students come from a variety of backgrounds. Some had experiences with overbearing or notably absent influences of Judaism. Others felt solidarity against anti-Semitic violence across the country or fury from anti-Semitic remarks in high school classes. But everyone has questions about identity and belonging.

The evening begins with a 30 minute service in the dining room. There are rows of students sitting on loosely organized chairs facing the students who are leading the service. Leah Burian is one of the students that leads services. She plays guitar while she sings. This is Burian’s second year helping lead services at Hillel. She is a sophomore music history major at UO.

Burian leading services is unique because she had never led a service before attending Hillel, and she had never even heard any of the songs. “If you grow up going to services, you can go through the motions,” she says. “But I had never done that.”

Burian is Jewish, but growing up, she and her family were never members of a synagogue. Her Jewish identity was encouraged in her family as a part of her cultural heritage, rather than as a religious observance. Her paternal grandmother survived the Holocaust, escaping from Czechoslovakia before Hitler invaded in 1939. When her grandmother immigrated to the United States, she was eager to educate people about the Holocaust. She then founded a community for Humanist Jews, who usually focus on the culture and heritage of Judaism, rather than the religion.

“In a way, I was very active because of my grandma, and her connection and her need to educate people,” Burian says. “We did a lot of the traditions. I just never went to a synagogue. So going to Hillel was a new aspect of things for me.”

One of the most significant aspects of the community Hillel provides are the services being led by students. It’s a new experience for students to have peers leading services, because most students that come to Hillel grew up going to services led by their rabbi. Peers filling the roles that authority figures once did changes the tone of the service completely.

“Hillel has always wanted to focus on things being student-led, because it’s easier to engage if you have your peers up there leading the service,” Burian says. “And there’s not as much pressure as a leader. If you mess up, it’s not the end of the world. We’re all just having a good time singing.”

Like most of the people in Hillel, Burian isn’t dressed up for the service. She wears a black turtleneck, jeans and chacos. Around her neck, shining off a background of black fabric, hangs a golden Star of David necklace. She hasn’t always had the necklace. Wearing a symbol of her identity became crucial to her after the Pittsburgh shooting in 2018, when 11 people were killed in a synagogue during Passover.

“I hadn’t really worn anything that would identify me as Jewish before, but after the shooting, I specifically bought a Star of David necklace, and I was like, ‘I’m going to wear this every day,’” Burian says, gently touching her necklace. “I felt it was ridiculous that I should have to hide who I am. Especially after my whole childhood growing up, I hated my hair. But that’s a stereotypical thing. Jews have curly hair. But it was still something I struggled with a lot.”

While the service is going on, some students retreat upstairs to play games, choosing to not be present for the service at all. Aaron Silberman, also a sophomore at UO, is occasionally one of those students. Unlike Leah, who attended Hillel the first Friday of her first term, Silberman was unsure if Hillel was right for him.

Silberman’s family are members of a synagogue, and he attended services regularly growing up. When he got to college, his parents encouraged him to go to Hillel so he would continue to be involved with the Jewish community.

“I knew it was an organization that was there for me,” Silberman says. “But I also felt like I wanted to do my own thing in college. And with both of my parents telling me I should go, I kind of looked at it like, I would be doing it because they wanted me to, not because I wanted to. So I didn’t go for all of fall term.”

Silberman had struggled to find a welcoming group of friends during his freshman year, and Hillel offered a community that was there when he needed it the most.

“I didn’t really make friends at school until this year. Last year, I was plagued by bad friendships, but that’s how freshman year is. This year, I actually found friends that treat me with basic human dignity,” he says, laughing. “I wouldn’t have found that without Hillel.”

Part of Silberman’s hesitance to commit to his religion further has to do with new perspectives he’s gained in college. During his first term at UO, Silberman took a class on genesis that challenged his views on the religion, forcing him to ask questions about what he believed in a way he never had before.

“Having the opportunity to learn for myself, that’s been a really pivotal thing in how I view my religion and how I view me. I don’t know if I believe more or if I believe less, but I’m building my own foundation as opposed to having that foundation thrust upon me,” he says.

Despite questioning his relationship with his religion, Silberman is planning on going on a Birthright Israel trip this summer, a free trip for Jewish people who are 18 to 26 years old, to explore the birthplace of Judaism.

“I’m looking forward to the trip and looking forward to being in the holy land,” Silberman says. “It’s a once in a lifetime thing.”

When the service is over, everyone puts away their prayer books, called Siddurim, and they get up to rearrange the space into a functional dining room. They bring out folding tables and spread tablecloths. When they’re finished, they gather in the foyer of the house. First, students pass paper cups filled with wine or grape juice around on trays, and when everyone has a cup in hand, they say the Hebrew prayer for wine together. The cups are thrown away as three large loaves of challah bread are uncovered and distributed. People form clusters around each loaf, every person resting their hand upon it. They say the Hebrew blessing for bread quickly, laughing and making excited glances to each other before ripping the loaf apart into fist-sized chunks. The bread is gone only moments later, in the time it takes for everyone to form a messy line toward the table where dinner is laid out.

Hillel hosts home-cooked dinners every Friday night. Andy Gitelson, the executive director of Oregon Hillel, often cooks the dinners himself in Hillel’s kitchen. But students also frequently come volunteer to help prepare the meal in the hours before the service begins.

“We have some students that come and help us all day Friday and get ready for Shabbat, but they have no desire to sit in that room and pray,” Gitelson says while preparing chicken and vegetable skewers to be barbequed. “And that’s okay. Come volunteer for your community. Create something for everybody else to take part in. Take pride in that, and have a great Friday night.”

Hillel just changed its mission statement last year. It is now “a catalyst for connecting students, building community and inspiring leadership through Jewish values,” according to its website. This is different from previous years, when its mission statement said it was mainly dedicated to Jewish students.

“Times have changed,” Gitelson says. “We see our values as being here for all students.”

This motivation to include more people in Hillel has a lot to do with Hillel’s hospitality, but it also emphasizes encouraging diversity and acceptance by welcoming the rest of the student body into the Jewish tradition.

“If a non-Jewish student sees anti-Semitism happening on campus, they don’t think about just some random Jewish community,” Gitelson says. “They think, ‘No, I’ve visited that community. I’ve been a part of that community. I’ve eaten dinner there on a Friday night, and this can’t stand.’”

Hillel still devotes a lot of its resources and time to serving the Jewish students on campus. It advocates for Jewish students at UO, often helping to facilitate the observation of important holidays. The first week of fall term this year started a day late to observe Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. The observance was the product of five years of discussion with the UO admissions office.

“Sometimes when you’re in a minority community, simply recognizing the conflict, saying, ‘As a university, we recognize this is a conflict for you’. That can be really reassuring,” Gitelson says.

Gitelson emphasized that Hillel’s central role is to empower its students.

“It is certainly our approach that we don’t think we have all the answers,” he says. “I want students to see that Judaism can look like a lot of different things.”

“And I do think that’s where a lot of students are at — a question of how do they fit and where do they fit.”

Aaron Silberman’s younger sister, Lilah Silberman, is a freshman at UO who is beginning to figure that out for herself. The one thing she’s sure of, however, is that she appreciates being Jewish more now.

“In high school, I had a tenth grade English teacher make a gas chamber joke,” Lilah says. “There were swastikas drawn in school lockers and bathrooms. But school leadership didn’t do anything about it.”

“Here, I can be Jewish,” she says. “I feel accepted, and I really like that. I have always felt safe here.”

For most of her life growing up, her experience being Jewish wasn’t exactly what she wanted it to be. “My parents always forced me to go to services for holidays and I’d hate it. It was just boring,” Lilah says. “But now I’m in college, and there’s Hillel,” she says, smiling widely. “It makes me like being Jewish.”

Lilah likes to stay at Hillel even after dinner, because after most people have left, the remaining students will reposition the tables in the dining room for game night. Game night is a new, entirely student-organized tradition that just began this year. Students bring their own board games and card games to Shabbat so they can play and spend more time together when it’s over.

Maddie Schaeffer, Hillel’s development associate, is excited about how the energy around Hillel is growing. “You can feel it when you’re in the room. You can feel that people want to be here,” Schaeffer says. As a staff member, she is particularly excited about game nights. “That is such a good symbol of a strong Jewish community. We set up Shabbat. We cook for Shabbat. We clean up for Shabbat. Then we leave, and students are still there. That means a lot.”

The strong community Hillel provides has already made a large impact on Lilah’s experience in college as she navigates a new environment. “I look forward to it every week,” she says. “Every day I get closer to Friday, I know that it’s going to get better. Fridays are my favorite because I get to be with people who are a little more understanding of the stress, of the friend troubles, of the experience.”

“It’s a community,” Lilah says. “Everyone wants to hear what you have to say. Everyone is there for each other, and that’s what makes it so nice.”

Sarah Birch (left) and Leah Burian (right) lead the Friday night student service at Oregon Hillel, a student-centric Jewish community at the University of Oregon. Photo by Keven Salazar

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)