Sitting at the intersection of Walnut Street and East 17th Avenue in Eugene is a quaint, cream-colored, Craftsman-style house. A resident tends to the vegetable garden in the front yard, and charmingly eclectic furnishings decorate the house’s interior. Downstairs, there are shelves filled with books and games, and houseplants rest atop various surfaces. Savory smells flow out from the kitchen. A journey up the stairs reveals a bright hallway that is painted yellow and lined with bedrooms. This house is more than a place where people live. For the nine residents of Walnut Street Co-op, it is a home.

But despite sharing living spaces, meals, resources and household responsibilities with one another, these residents are not a family –– at least not a biological one. This household is an intentional community.

Intentional communities are defined by the Foundation for Intentional Community as “groups of people who have chosen to live together or share resources on the basis of common values.” They consist of five or more people and may be organized around shared social, spiritual or other beliefs. Physically, they can be one house or multiple structures and range from urban to rural locations. Because of the more cooperative nature of intentional communities, they can provide more sustainable lifestyles.

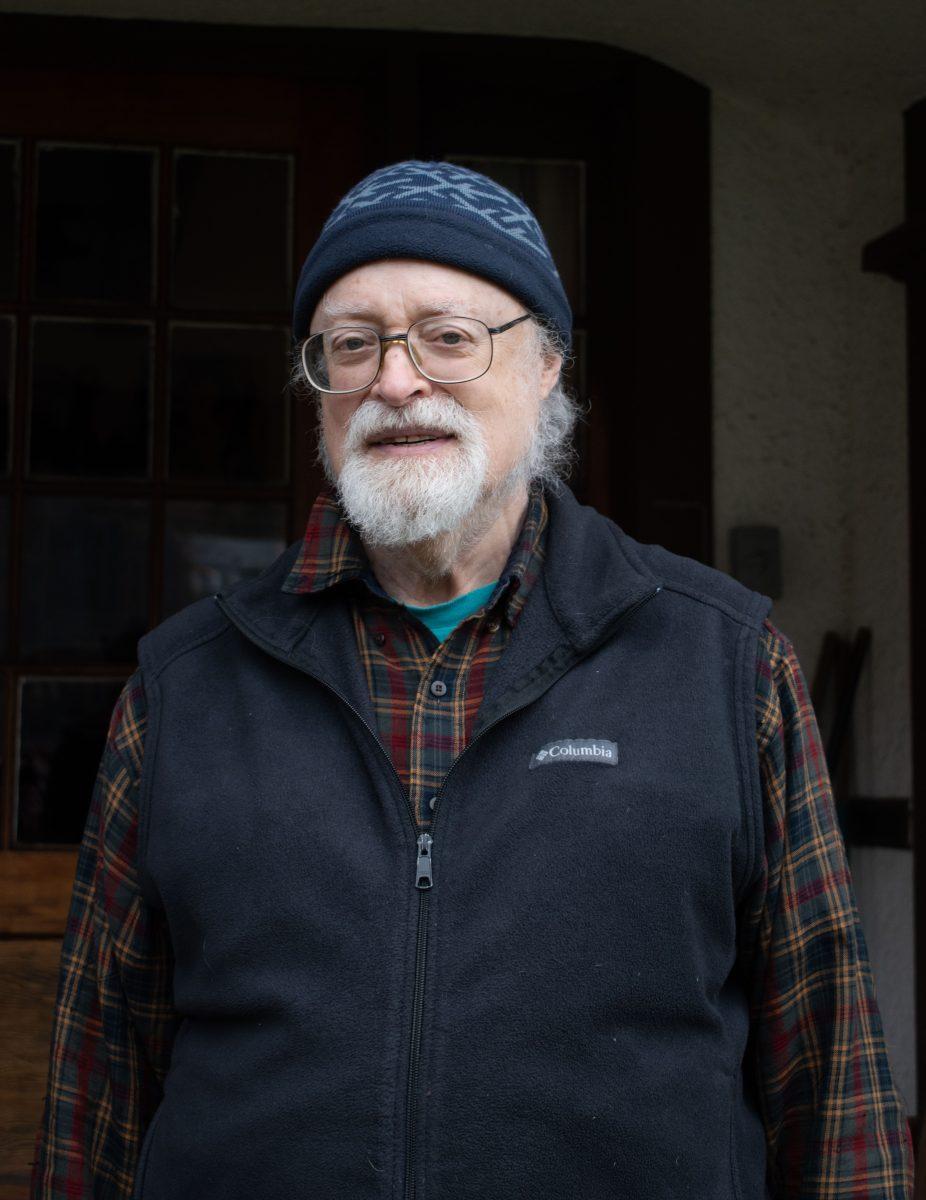

“We are moving from this absurd form of living that is now standard in our culture to something that is a little more like the way people have traditionally lived,” Tom Atlee, activist, author and member of Walnut Street Co-op for 20 years, says.

At Walnut Street Co-op, ecological sustainability is a core value –– as are cooperation, community, communication, democracy, fairness, personal awareness and collective intelligence.

Atlee and other members of the co-op practice sustainability by buying food in bulk, purchasing organic and local foods, cooking mostly vegetarian and vegan, gardening, composting and sharing resources amongst members of the household. Sharing resources – such as household appliances and products, food and more – is an essential practice for intentional communities like Walnut Street Co-op, and it reduces consumption, according to Atlee.

“People have things that the vast majority of time they’re not using. And, under the right social organization, those things could be used by other people,” Atlee says. “Living collectively, you don’t need more than one or two hammers or whatever.”

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, plastic products – which non-bulk food is often packaged in – accounted for 12.2% of all waste produced in the United States in 2018. Emily Kostuch, another member of Walnut Street Co-op, notices the co-op produces less waste than other households in the neighborhood due to the nature of their lifestyles –– particularly because they purchase food in bulk. By buying food in bulk, the co-op reduces their single-use and plastic product waste.

Kostuch also says she has become more eco-conscious since living in an intentional community.

“I think more about where my food is coming from and packaging that food comes in,” she says.

Living a more sustainable lifestyle guides many intentional communities and can be a big motivation for individuals – like Kostuch and Atlee – to join them. Some members also like the constant support from others.

Kostuch says she appreciates the relationships she’s gained as a result of her involvement in intentional communities. Kostuch says these relationships are a source of strength and support, and living in intentional communities has been beneficial to her mental health.

“If I was living on my own, I feel like I would have a mental breakdown,” she says. “If I’m feeling anxious and I want to go be near someone, I can do that.”

The community-oriented lifestyle Walnut Street Co-op provides has been especially beneficial during the coronavirus pandemic for some members, including Morgan Raikes-Bennett. He says living at the co-op has helped him feel less isolated.

Walnut Street Co-op has fostered community for its residents during and prior to the pandemic through activities such as board games, group dinners and group meetings. These activities provide spaces for members to come together and connect amidst their individual lives.

“We’re a co-op, but we’re also a collection of individuals doing their own lives, and it’s very possible to go a full week without really seeing another person even though we share the same space,” Raikes-Bennett says. “The meetings are nice to be able to have a once a week check-in, and similar – that’s what meals represented, too – is community building on a regular basis.”

Raikes-Bennett says group dinners currently take place about three times a week and are foundational to how the co-op lives its values.

Between a number of members shopping for food, others cooking the meal itself and clean-up, group dinners need planning and teamwork. The process of working together to produce these dinners fosters community according to Raikes-Bennett, and it comes to fruition when everyone sits down at the co-op’s large dining table to eat with one another.

Another motivation for individuals to join intentional communities is the availability of housing. Providing affordable housing is a part of Walnut Street Co-op’s mission, and it is what drew Raikes-Bennett to become a resident there.

Raikes-Bennet says he was in need of stable housing when he decided to look into Walnut Street Co-op with his sister. While his sister decided not to join the co-op, Raikes-Bennett has been a resident there since 2017. He says he didn’t know if he was fit to live in cooperative housing, but he’s had an impactful experience and benefited in many different ways.

“Something I’ve gotten from the co-op is that each individual brings their own background and what they love,” he says. “And that’s very evident in how we share food and cook for each other. I’ve been exposed to so many different vegetables and dishes.”

Kostuch and Atlee both say the co-op works because of the unique passions and skill sets of its residents — Kostuch says there are members of the household who love to garden and lead a gardening committee.

However, navigating the various perspectives of such a diverse group of people presents challenges at times, according to Atlee. He says communicating and interacting with other members of the co-op in a productive manner is important to create healthy relationships and build community.

“You have your perspective, but you don’t expect to get whatever you want or to be privileged in terms of your voice mattering any more than anybody else’s,” Atlee says. “So it’s a lot of personal growth.”

Raikes-Bennet also says, to be respectful to other members of the co-op, it is sometimes necessary to make small lifestyle changes – such as abiding by quiet hours or other community agreements – which can be difficult. Holding residents accountable to these community agreements while still being understanding of their circumstances can also be challenging.

Intentional communities like Walnut Street Co-op also deal with judgment from those outside of the co-op. According to Kostuch, one such assumption is the idea that the co-op is a cult.

Additionally, Raikes-Bennet says some people believed he was going to be living on a commune when he told them he was moving to the co-op. However, these stereotypes do not represent the reality of Kostuch, Raikes-Bennett or others’ experiences.

“It’s easier to talk confidently about something you’re ignorant about, especially if you’re going to talk disparagingly,” Raikes-Bennett says.

Kostuch says her family has been supportive of her involvement in intentional communities and even visited Walnut Street Co-op for the first time last summer.

She says her parents believe she’s just “doing her thing.”

“I definitely know that my family doesn’t fully understand what I do here,” Kostuch says. “We’re just people that want to help each other.”

Atlee stands on the Walnut Street Co-op’s front porch. His activism work is a foundational element of the Co-op, both as a way of fostering community and to guide the Co-op in its sustainable and affordable goals.

![[Photo Courtesy of the Lara Family]

Ruben embraces his beloved childhood goat, Katrina.](https://ethos.dailyemerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/katrina-1-1060x1200.jpg)