The only thing worse than a nightmare is waking up paralyzed.

Story by Nina Strochlic

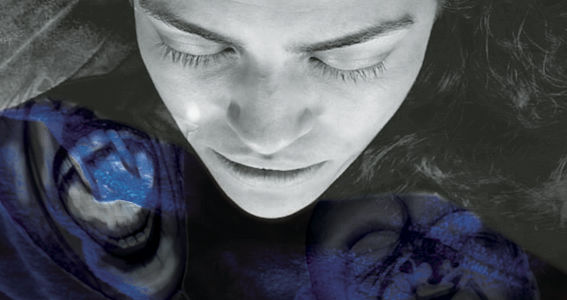

Illustrations by Paul Raglione

Photo by Blake Hamilton

It takes a moment for realization to dawn and terror to set in. Awoken with a start in the middle of the night and aware of her conscious state, the heavy pressure weighing on Kansas Keeton’s chest is inexplicable. A dark presence moves menacingly just beyond her range of vision, though she can tell it’s nearing the bed and certain it’s right next to her. As soon as she tries to cry out for help, she discovers it’s become completely impossible to move or speak; her body is paralyzed. Her lungs constrict as the crushing weight grows heavier, pushing out all remaining oxygen. Her mind races with fear, but her body remains immobile. A few minutes later all unusual sensations have vanished, leaving her to wonder if she just survived an encounter with the supernatural.

For many, the series of events described sound like they could be drawn from a scene in a just horror film, but for University of Oregon sophomore Kansas Keeton, this is a weekly occurrence. Since her senior year in high school Keeton has suffered from sleep paralysis, a sleep disorder shrouded in mystery and laden with culture-specific beliefs ranging from witch attacks to vengeful hauntings.

Scientists and researchers have been investigating the causes and cures for sleep paralysis in the past thirty years and have begun assembling a conclusive explanation. Sleep paralysis occurs during a hypnagogic state — a gray area straddling sleep and consciousness — while the sleeper is susceptible to hallucinations. During the deepest period of sleep, the rapid eye movement or REM cycle, the brain emits signals stopping the body from enacting dreams being played out in the sleeper’s mind. So, while the legs may still race, the mind is still absorbed in a dream. When sleep paralysis victims inexplicably wake up during this stage they are horrified to find their bodies virtually paralyzed. During sleep paralysis the mind and body do not transition properly between being fully awake and REM sleep; if the sleeper abruptly wakes up from their REM cycle or enters into it while awake, the result is a conscious mind struggling to move in an immobile body still stuck in the sleeping state.

Overall, sleep paralysis is an explainable phenomenon. “The hypnagogic experiences are remarkably consistent with what we know about the underlying neurophysiology of REM states,” says Dr. Allan Cheyne, former chair of the Department of Psychology at the University of Waterloo, Canada.

Researchers have categorized the most commonly experienced sleep paralyses into a three-pronged model. All of which include immobility. The first called “The Intruder,” referring to visual and auditory hallucinations and the fearful sensation of a nearby presence. According to Dr. Cheyne, these feelings of intense terror are triggered by the activation of fear centers in the brain, which is a known characteristic of REM sleep. The next experience is called “The Incubus,” where the sufferers feel a heavy weight on their chest and has difficulty breathing — attributed to the paralysis of muscles controlling voluntary breathing. Fortunately automatic breathing remains regular. The last and least common, called “Unusual Bodily Experiences,” is when the sleeper has an out-of-body experience, including floating or flying sensations. This version of sleep paralysis is often the basis of claims ranging from alien abductions to angelic visits and is caused by malfunctions in the area of the brain coordinating the body’s orientation.

Surprisingly, sleep paralysis disorder well below the American mainstream radar and virtually unknown to anyone outside the fields of medicine or psychology. However, according to Dr. Cheyne about 25 percent of Americans report having experienced sleep paralysis at least once. In his research on sleep paralysis, Dr. Cheyne has collected more than 40,000 accounts from around the world and he believes reasons for the obscurity of this condition may be found in cultural stigma.

“The difference between traditional and industrialized cultures in knowing about these experiences is striking,” Dr. Cheyne says. “Interestingly, in Japan [where forty percent report experiencing the condition], they do have a term for sleep paralysis, ‘kanashibari,’ as they do in Newfoundland, ‘the old hag.’ In both these cultures, the reported incidents appear to be much higher [than] reported experiences in North America.”

In South Korean society, beliefs about sleep paralysis, called “gawee nulim,” are pervasive. When the topic came up in her psychology class, junior Hailey Im was surprised to discover how few Americans knew what the condition was, compared to her native South Korea. Belief in ghosts is an ingrained aspect of many Asian cultures and often infiltrates into the explanations behind sleep paralysis. “A lot of people see a ghost and they think it’s that ghost hunting them down,” Im says. Korean student Hannah Yoon expatiates further on these beliefs. “Asians believe in spirits and ghosts and say the ghosts are sitting on them or that it’s just spirits having fun,” she says.

Those inflicted by sleep paralysis are often caught in a doublebind: too embarrassed of their unusual situation to ask for help from their family or doctor lest they be considered psychologically unstable, but afraid of the unknown assault they survived. These people struggle between what they know they saw and their rational belief in its probability. Keeton says she experiences sleep paralysis about once a week. At first, she had no idea what to make of her strange nighttime condition. “For a while I thought it must have been some spirit and I did think I was going a little insane,” Keeton says. She remembers wondering, “‘Why is this happening to me?’”

Dr. Cheyne, whose name is plastered on seemingly every research article on the subject, has used his years of research to craft a simple explanation for the phenomenon. “Susceptibility to sleep paralysis appears to be a relatively minor problem of the coordination of transitions between different physiological states. On one hand, the transition between waking and sleep, and on the other, the transition between REM and non-REM states,” he says.

The hazy division between dreaming and sleeping at this point sometimes allows dream-like visions to infiltrate into the waking world. “I think we fill in the blanks with our deepest fears because we are in such a vulnerable state and come up with the most frightening scenario possible,” Keeton says. Many sufferers report seeing hooded men, demons, or other threatening creatures lurking about their room — though hallucinations are not always incorporated into the experience.

While experiences as a whole vary case by case, the feeling of being watched or attacked by a demonic presence is omnipresent in sufferers’ accounts. Buzzing noises that sound like talking, a heavy weight pressing on the chest, and shadowy movements are all common features of the attack described by those afflicted. For those who have experienced this nightmarish waking-state, a scientific theory may be hard to settle for. Instead, many classify the lucid event as a near-death or paranormal confrontation, turning the phenomenon into breeding grounds for legends and myths across the globe.

Chiedza Chikawa recalls her first encounter with the nightmarish experience. “I wake up, I want to move, but I can’t move,” she says. “I felt like something was holding me down, I opened my eyes and tried to yell to my sister, but I couldn’t even say anything.” While Chikawa is unsure what the experience was triggered by, beliefs in her native Zimbabwe are definitive. “People from my country think it’s an attack on your spirit; they believe it’s black magic, and you could possibly die if you can’t get out of it.”

Senior Jason Moon, has had reoccurring encounters with this terrifying disorder, but none as memorable as his first. “My sensation was that I could just barely open my eyes by forcing them, and I could see my dorm-room ceiling,” he says. “I felt awake; however, I could not move — my body was completely rigid. I was trying to yell at my roommate to wake me up but I think I was barely able to squeak out a gurgling noise.” Moon watched, paralyzed, as a small geometric shape rotated above his head. “It was a scary sensation; I really wanted it to be over as soon as it started.”

A popular interpretation leads the condition to be labeled “Old Hag Syndrome” in parts of the world. The name stems from British and North American folktales that attribute the disorder to an ancient, malicious woman who sits on top of sleepers and sends them nightmares or tries to suffocate them. In Newfoundland, Canada, a widespread belief is that someone with evil intentions can send the hag to inflict others. Other cultures use similar analyses to explain the weight they feel — their unique nuances in interpretation lend insight into embedded cultural norms, beliefs, and superstitions.

“I can definitely see why some people would consider this supernatural,” Moon says. “It was not only a very bizarre, conscious hallucination, but it was accompanied by this indescribable feeling of dread and panic.”

Sleep paralysis is far from being a modern ailment; in fact, a Chinese book on dreams dating back to 400 B.C. explains the experience of similar occurrences. Later, in the second century, another reference is made to sleep paralysis when Greek physician Galen attributed it to indigestion and gastric problems. Recent historical events may also have a basis in this phenomenon. Some theorists believe that accusers in the Salem witch trials were afflicted with sleep paralysis, and their claims of being sat upon and suffocated in a nighttime assault by witches can be blamed on the symptoms of this disorder. The etymology of the word “nightmare” also shows the historical pervasiveness of sleep paralysis. By the 19th century, the word simply meant a bad dream, but in 1300, “nightmare” referred to an evil female spirit suffocating victims in their sleep — a figure almost certainly inspired by the experience of sleep paralysis.

Some studies attribute sleep paralysis to narcolepsy, unhealthy sleeping habits, or those prone to panic attacks; however, they also note that it seems just as likely to occur to an average, healthy person. Surveys of those inflicted have found that sleeping on your back or sudden changes in sleep schedule may be linked to this experience as well. Lisa DeJongh, a sleep technologist at the Eugene Sleep Disorders Center, believes it correlates with workload. “Usually, paralysis doesn’t happen on a regular basis. It tends to happen during stressful times and generally more with college and high school kids,” she says.

People suffering from childhood trauma or post-traumatic stress disorder may also be more likely to experience sleep paralysis, especially in areas afflicted by recent wars. Survivors of Cambodia’s brutal Khmer Rouge regime have linked their experiences with sleep paralysis to beliefs that the ghosts of murdered family and friends are returning to assure they have not been forgotten. As many as 50 percent of Cambodian refugees cite experiencing sleep paralysis and many attribute their nighttime assaults to hauntings by angry spirits.

Remedies for sleep paralysis prevail in folklore around the globe. For some, wiggling a finger will gradually bring mobility to the rest of the body. “The first thing I try to do is move my finger. I can’t explain why, but I focus on my finger and sometimes it works,” says Jae Lee, a junior from South Korea. Moon was able to snap back into consciousness once his roommate said his name. Others find refuge in their faith. “When I told my dad about it, he told me to burn incense and pray. I find that prayer really helps me when it’s happening,” Chikawa says.

Back in her pitch-black bedroom, Kansas Keeton has regained full control of her body, but she’s less than reassured. She knows any relief may be short lived because she could wake up to that terrified feeling over and over again in one night. After three years, Keeton knows what to expect from sleep paralysis, but this does little to quell her fears. “When it becomes more frequent I dread going to sleep,” she sighs. “Your brain is saying ‘wake up, just move’ and you can’t.”